The Making of Tawang Monastery and The Monpas: Explore the historical significance of Tawang, its ancient trade routes, and the construction of the renowned Tawang Monastery. Discover the Monpas, the dominant tribe in the region, and their contributions to the rich cultural heritage of this district in Arunachal Pradesh, India.

Tawang, which is part and parcel of Arunachal Pradesh and is a proud religious and cultural symbol of the Monpas, has of late been in the news with the Chinese trying everything possible to show it as the bone of contention between India and China. Clearly after the McMahon Line was drawn by the British, Tawang became a legal part of India which was administered legally by the Indian government. The Chinese continue to raise Tawang as an area of contention at special representative meetings between China and India. Beijing has often used religion as an argument particularly the birth of the 15th century Dalai Lama in Tawang to lay its claim on this historic district of Arunachal Pradesh.

However, that does not take away the fact that Tawang has its own history of evolution which includes its historical connections with Tibet and why it has come to become a seat of an important Buddhist center in India’s eastern flank. Thus, the history of Tawang, its progress and development and the contribution of the Monpas to withstand challenges that were posed by aliens in the disguise of ecclesiastic Lamas to make it what it is today deserves a deeper understanding.

Tawang is a district in Arunachal Pradesh which is located in the high-altitude westernmost part and is considered strategically important with borders with the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) to its north and Bhutan to its west and south. On its east is the district of West Kameng.

Tawang has always been important since the days of yore. It was a key ancient caravan trade route that passed through the region and connected the Tibetan plateau with the plains of Assam. Geography of the region was such that it was not physically possible to link the Tibetan plateau with the annual traditional marts in the foothills of Assam plains bypassing the Tawang region.

Further, since the 17th century Tawang became doubly important as the all-important Tibetan-Lamaist Buddhist monastery was constructed here. Soon it became important as a Buddhist pilgrimage for the Monpas in particular and for the people of the world in general. Incidentally, the Monpas are the dominant tribesmen group in Tawang and the neighbouring district of West Kameng.

The history of existence of the Monpas at Tawang can be traced to the 500 BC to 600 AD, when the kingdom of Lhomon or Monyul ruled the area. According to reports available, “the Monyul kingdom was later absorbed into the control of neighbouring Bhutan and Tibet.” The reports further states that the monastery was founded by Mera Lama whose real name was Lodre Gyatso in 1681 in accordance with the wishes of the 5th Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso, and has an interesting legend surrounding its name, which means “Chosen by Horse”.

The Tawang Monastery

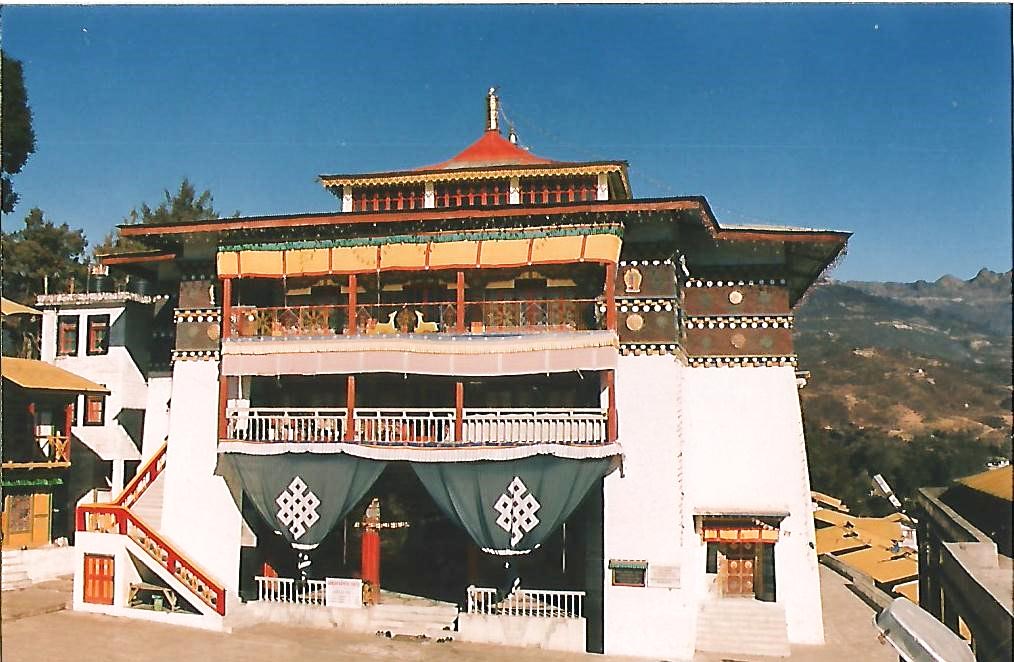

The myth goes that Mera Lama, who hailed from the village Mera near Tawang had a mission assigned to him by the 5th Dalai Lama to find out a proper location to establish a monastery at Tawang. But Mera Lama after a long search could not find any suitable site. One day, exhausted as he was, retired in a cave to take some rest and out of fatigue slept for some time. Afterwards he came out of the cave and was looking for his horse. He then found it grazing on a flat mountain top. He thought that it was a divine direction and probably found the place most suitable for the monastery. Soon he sought the help of local people of Tawang to build the monastery. The monastery, as estimated by the people, was built sometime in 1681. (Plate 1)

It all started sometimes in the seventeenth century when the Gelukpa sect of the Mahayana Division of the Tibetan Buddhism in its Lamaist form made entry into the Tawang area at a time when the pre-Buddhist traditional religion of Bon, as practised in Tibet was at its zenith. It is widely known that the Guru Padmasambhava, the Indian saint, paid a visit to Tawang region not directly from India but from Tibet. His visit was much earlier to the construction of the Tawang monastery and it was in the eighth century.

The revered Guru meditated in an isolated mountain cave above Zemithang near the Indo-Tibet border. Now a temple has been constructed there and is known as the Taktsang Gompa. Guru Padmasambhava is popularly known among the Monpas as Guru Rimpoche or Lopon Rimpoche. The author has in an earlier publication ‘Arunachal Pradesh: The Dynamic Monpas of Tawang: Tradition and Transformation,’ has elaborately mentioned about Guru Padmasambhava’s beginnings from a part of ancient India known as Uddiyana, believed to be in the Swat Valley in the undivided Kashmir and presently in the northern Pakistan. The region was much known for magical preachers and Tantrism since the long past.”

Before the Gelukpa sect could establish its supremacy in the Monpa country the other two sects known as Nyingmapa and Kargyupa were quite active in the region and Gelukpa was the last to arrive. However, with the establishment of the Tawang monastery the Gelukpa slowly but steadily established its stronghold while the other two sects, namely, Nyingmapa and Kargyupa lost footing.

In this context it is pertinent to mention the observation made by Niranjan Sarkar in his book Buddhism Among the Monpas and Sherdukpens (1980). The author observed that, “These traditions linked to known history of Buddhism show that the conversion of the Monpas was probably started by Padmasambhava in the eighth century and the Nyingmapa must have had a good following among them even before the twelfth century to have established the three Nyingmapa temples of Urgyeling, Sangeling and Tsorgeling at Tawang possible.”

He further adds that “It is not possible nowadays to know when the Karmapa (one of the sub-sects of Kargyupa) was first introduced in the region. But this sub-sect had a sizable following among the Monpas by the twelfth century as evidenced by the establishment in this period of the Karmapa temple at Kimnesh…”

However, with the establishment of the Tawang monastery in the 17th century, Gelukpa, the last sect to enter the scenario of the Monpa religious life prevailed over the entire erstwhile Kameng district up to the foothills bordering Assam. Gradually many monasteries and a few nunneries were built, the biggest being the Tawang monastery. These monasteries and nunneries became the focal points of the religious lives of the Monpas. The Tawang monastery which has a capacity to accommodate five hundred Lamas at a time is still considered a prominent institution of the Gelukpa sect in the cis-Himalayan region.

Structural Significance of The Tawang Monastery

The Tawang monastery, the only functional Tibetan-Lamaist Buddhist monastery in the cis-Himalayas after Lhasa, is situated on a high cliff having quite a big campus and a number of high buildings of Tibetan style. It is the norm with the Monpas to construct the monasteries on the highest possible elevation. The elevation should be such that no private houses or other constructions could be built at the same level or above the Gompa (local term for a Tibetan-Buddhist monastery). The people give a simple reason for it and say that the house of God should always be on an isolated cliff undisturbed by worldly temptations.

The Tibetans and the Ladakhis also believe in the same way. In this context, Anthropologist R S Mann is of the opinion that there is a background to why the Gompas are built on high elevation. “Religious performances being the most important in the Ladakh life are not disturbed by any noise. At the same time their identity is also maintained,” the author observes.

It is important to note that Mera Lama was extra cautious to build the Tawang monastery in such a spot that it remains naturally secured from the southern and western sides by very steep and perpendicular gorge making it physically impossible for anybody to climb. It was wisely thought so to keep the monastery secured from the attacks of the Dukpas of Bhutan from those two sides.

Incidentally, the Dukpas of eastern Bhutan belonged to the Nyingmapa sect and were against the Gelukpa advancement in Tawang. Thus, to keep the Dukpas at bay the structure of the monastery was designed to be defensive. It is felt that the monastery was strategically built to have a long-term military advantage too. The monastery has been found to be accessible from only one side and that is the north along a ridge. However, the eastern side is open with a gentle slope. The inmate Lamas who were also militarily trained were required to keep a strict vigil only on the eastern side while the southern and western edges were already secured. Nevertheless, in spite of the security measures the monastery soon after its construction faced hostility from the followers of the sects of Karmapa and Nyingmapa. The Dukpas of Bhutan also made several attempts to capture the monastery but failed. This explains its strategic location and defensive structure.

The Tawang Gompa in the past practically played two roles, propagation of religion and military post against the hostilities against the Dukpas of Bhutan.

Mera Lama gave a greater importance to the military activities in the monastery and he wanted more and more people to actively join in the defence of the monastery and the region as a whole.

Niranjan Sarkar in his work titled, “Buddhism Among the Monpas and Sherdukpens (1980:25),” writes that “Mera Lama gave so much importance to the second aspect that he lifted all prohibitions against the military activities from the inmates of the monastery. Out of the monthly allowance of thirteen brae (a measure bit more than a kilogram) of cereal, as much as ten are said to be given as an inducement to actively join in the defence of the area.”

It is also a norm with all the big Tibetan-Lamaist monasteries that there should always be a Shyo village just below the monasteries and these settlements were historically populated by the economically poor families, mostly landless. The inhabitants of the Shyo villages were also called Shyo everywhere.

The Shyo people were always exempted from paying tax to the Tibetans but in lieu had to accommodate the pilgrims free of cost during important Buddhist festivities in their homes. It is because in those days paid accommodations such as hotels and inns were not available for the pilgrims from the fur-flung areas. In the case of the Tawang monastery the Shyo village even served another purpose. The Shyo people kept a strict watch in and around their settlement and on the first sight of suspicious looking people used to immediately alert the inmate Lamas. So the monastery was safe from all directions and aspects.

At the entry of the monastery over the ridge in the north there is a gate called Kakaling in local tongue. It is a square hut-like structure. The ceiling is decorated with paintings of Buddhist divinities. A paved path from the Kakaling leads to the courtyard of the Gompa passing by a number of buildings within the premises of the monastery. Religious dances and other outdoor activities and ceremonies are held in this courtyard. On the western side of the courtyard stands the library of the monastery.

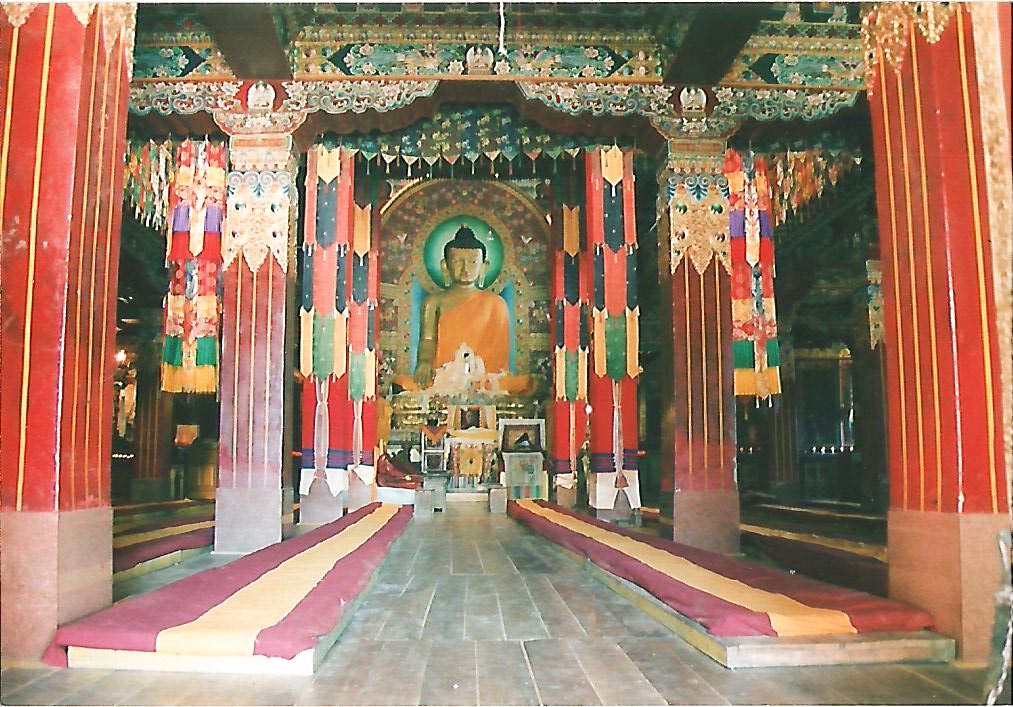

The assembly hall known as the Dukhang is the most impressive building. It is a three-storied structure. There are rows of seats for the Lamas placed longitudinally from north to south. Chubirs, the long decorative cylinders made of colourful cloths with open upper and lower ends hang from the ceiling. The guardian deity of the Tawang monastery is Palden Lhamo. From the monastery the township of Tawang could be seen very clearly.

Furer Haimendorf (1982:164) in the ‘Highlanders of Arunachal Pradesh: Anthropological Research in North-East India,’ rightly observed that, “Unlike many of the monasteries of Ladakh, which recently entered a phase of decline, it (Tawang monastery) is fully operational and novices continue to be recruited from most of the villages of Tawang district.”

The Presence of Tibetans in Tawang’s Past

The Tibetans were very much present in Tawang and ran the day-to-day affairs of the monastery even before the sixth Dalai Lama. The Monpas, being God fearing people and had a strong belief that every good action took them a step towards spiritual gain and divine elevation. It was a practice by the Monpas to voluntarily give away material goods to the monastery and turn the prayer wheels with the mystic formula OM MANI PEME HUM written on them. They used to light the butter lamps in the monasteries, used to turn the beads on the rosary and even contributed voluntary labour for the maintenance of all the Buddhist religious shrines.

It can be presupposed that the Tibetans from Tibet in their course of the caravan movements to the annual marts to Assam foothills and on their backward journey interacted with the Monpas and found that the people were simple and the country was quite productive compared to their cold desert of Tibet. This particular information contributed to the Tibetan ecclesiastic think-tank to extend their jurisdiction beyond Tibet up to Tawang and the neighbouring areas. In the subsequent period the Tibetans administrators in the guise of ecclesiasticism may have thought of exploiting the simplicity of the people.

This was the beginning of a gloomy period that the Monpas faced for generations. The Monpas could well understand the corrupt and shady atmosphere created by the Tibetan ecclesiastic rulers but they were so simple that they took it to be their fate as they had none to lodge complaints or seek justice. And for centuries the people were cursed, punished and left to survive in an absolutely poor state.

In the context of the exploitation of the Monpas by the theocratic Tibetans from the Tawang monastery following is an observation from the author’s earlier work titled, ‘Arunachal Pradesh: The Dynamic Monpas of Tawang: Tradition and Transformation (2018)’ – “The simplicity of the Monpas of the region of Tawang supplemented the interest of the Tibetans as they believed that it would be easy to persuade the god-fearing Monpas to make striking contribution in the name of the monastery and happily live on the regular contribution towards the monastery in terms of food grains and yak’s butter and keep their (Tibetan) coffer filled.

In the ancient past the devoted Monpas initially were supportive of the Tibetans as they thought that the Tibetan tyrants (in the disguise of theocratic Lamas) were in a better position to look after the newly constructed monastery and hold the daily worships. There is also a belief that the 26 feet huge wooden idol of the Lord was brought on head load from Tibet and placed in the monastery.

The Monpas must have felt obliged towards the Tibetans for this significant action as perhaps there were none in the Tawang area to carve out such a huge and exemplary idol of the Lord at that time. Perhaps due to their simplicity, the Monpas never were able to calculate the alleged desecrative and hypocritical attitude of the Tibetans’ ecclesiastic rulers. Hence, the Monpas never resisted the advance of the Tibetans in their land and it made the situation easy for the intruders. In no time the Tibetan activities in Tawang and its neighbouring areas became stronger and further substituted as the British-Indian colonial government was quite indecisive in taking over Tawang even when the Tibetans once relinquished certain regions to the British-India government that included Tawang.

This lack of judegment on the part of the British-Indian officials gave adequate scope and audacity to the Tibetans to continue with their exploitative activities in the Tawang region and make the most of the Monpas. The ambiguous and indecisive nature of the British-Indian executives gave licence to the Tibetan administrators who in the disguise of ecclesiasticism ruled over Tawang until the Independence of India. Not only up to 1947 but for a few years even after that.

The Tibetan ecclesiastic rulers might have hatched the idea at the back of their mind to convert the Monpas into serfs as they did to their fellow Tibetans in Tibet. For the benefit of the readers, it may be stated that Tibetan nobles and theocrats since ages were adept in economically exploiting the general population of Tibet and even went to the extent to convert them into serfs.

British diplomat Sir Charles Bell, who was regarded as “an expert on Tibet”, wrote in his book Portrait of a Dalai Lama: The Life and Times of the Great Thirteenth has been quoted in media reports as saying, “When you come from Europe or America to Tibet, you are carried back several hundred years. You see a nation still in the feudal age. Great is the power of the nobles and squires over their tenants, who are either farmers tilling the more fertile plains and valleys, or shepherds, clad in their sheepskins, roaming over the mountains.”

The same report observes that “Serf owners in Tibet were composed of local officials, aristocrats and high-level monks. They barely made up 5 percent of the total Tibetan population but possessed all the farmland, pastures, forests, mountains and rivers, and most of the livestock.”

The situation at Tawang and the plight of the Monpas was not unknown to the colonial officials of India. There were a few reports that suggested measures for welfare and betterment of the inhabitants of Tawang region as submitted by some of the officials of the British-India regime. Sadly, under different pretexts, the proposals were never put into operation by the colonial government of India.

In the meantime, the Tibetans started showing increased interest in Tawang and sent a high official with an escort of troops who started collecting taxes from villages far south of Tawang and issued summons to villagers as far as Rupa and Shergaon, in present West Kameng district. These villagers were the Sherdukpens and the Tibetan tax collectors claimed them to be Tibetan subjects and asked them to present themselves for official Tibetan enquiry. They not only claimed them to be Tibetan subjects but also told them that the Tibetan territory actually extended far to the south.

Hence it became a must for the Government of Independent India to take over the administration of Tawang and to bring the region within the political map of India. In the present context it may be mentioned that, “Even after attainment of Independence in 1947 by India, Tawang and its neighbouring areas were under alien occupation.” In fact the Government of the state of Assam following the Colonial legacy was regularly making a payment of five thousand rupees to the Tawang monastery as Posa annually. The dismal part was that all the cash collected from India was sent to the Drepung monastery. In addition, the monastery officials were merrily collecting Khrei without respite.

In the context of bringing Tawang region within the Union of India that took place in 19/20 February 1951 the author in his earlier work ‘Arunachal Pradesh: The Dynamic Monpas of Tawang: Tradition and Transformation (2018),’ has categorically observed that, “For bringing Tawang under Indian control the then Governor of Assam Shri Jairamdas Daulatram took the courageous and bold step. Governor Jairamdas convinced the decorated Naga officer, Major Ralengnao (Bob) Khathing, to take up this onerous task. According to available reports in various journals and media Khathing who the Assistant political Officer in the Indian Frontier Service posted at Charduar had expressed his reluctance, saying he wasn’t part of the army and could not take up the responsibility to which the Governor replied saying, “I am all the authority that you need, though neither the centre nor I have the ability to get the C-in-C Roy Boucher to agree to a military expedition for this task. At least not quickly enough to do it before the Chinese react’. Jairamdas mulled, adding “We need someone to do it quietly. Keeping in mind your war record, I cannot think of a better man to do it than you.”

Bob Khathing rejoined the Assam Rifles and led a retinue of Assam Rifles and marched to Tawang and annexed the region. It was the shrewdness and talent of the Major that he brought Tawang within India driving away the Tibetans by not even spending a single bullet.

The 1914 Simla Accord and the Dirang Dzong post

The 1914 Simla Accord established the McMahon Line as the new border between British-India and Tibet. This treaty caused Tibet to relinquish some of its territory, including Tawang, to the British. However, the British never took possession of Tawang and the Tibetans in the area remained in control. According to reports, when British botanist Frank Kingdom-Ward entered Tawang without permission from Tibet, he was arrested, which brought renewed attention to the Indo-Tibetan border. This revealed that Tibet had ceded Tawang to British India, yet Tibet still refused to surrender Tawang partially due to the significance attached to the Tawang Monastery.

According to some reports, as per Shakya 1999, the British made a strategic move to assert their power over Tawang in 1938 by sending a small military unit under Capt. G.S. Lightfoot. While the visit sparked a diplomatic protest from Tibet, it did not result in any territorial changes.

Reports suggest that, in the wake of the Japan War of 1941, the government of Assam took various measures under a “forward policy” to solidify their control of the North East Frontier Agency. J.P Mills established an Assam Rifles post at Dirang Dzong resulting in the extension of administrative control over the Tawang tract in 1944, according to India’s China War by Neville Maxwell, 1972. However, the government did not take any measures to oust the Tibetans from the area north of the Sela Pass, which included the town of Tawang.

The Monpas and The Tawang Monastery of Today

Even after three years of Independence, Tibetan monastery officials were collecting high taxes from the residents of Tawang and its surrounding areas. The Government of Assam was also paying an annual fee of 5,000 INR to the Tawang Monastery. The fear of taxes was so ingrained in the local population that even after Tawang was taken over by India, the Monpas were still worried that the Union Government of India would impose new taxes on them. Centuries of paying taxes to rulers had made it difficult for them to imagine a life without paying taxes. Reports have it that Major Khathing then gave them a lecture about India and its government, which would not exploit its people. This is how Khathing won their hearts.

Nevertheless, coming back to the religion part it has to be stated that the Buddhism as practised by the Monpas of Tawang and West Kameng district is a mixture of Bon and Buddhism. Bon is the original religion of Tibet since the pre-Buddhist period and it was also the belief pattern of the Monpas in the past. However, some relics of Bon is still visible in some places in Tawang district.

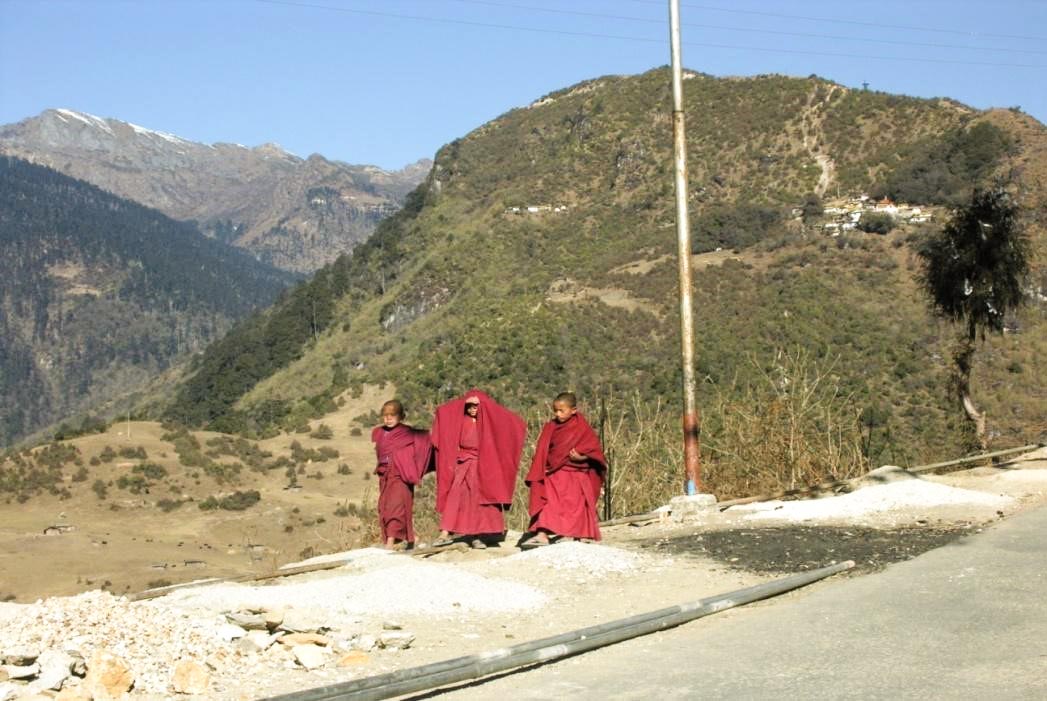

After the departure of the Tibetans the Monpa Lamas took up the responsibility of the daily worship and other activities of the Tawang monastery. A good number of the Monpas in general dedicated their lives to the monastery and monastic duties. It was a norm with Buddhist Monpas that those families who had three or more sons, the second son was to be given in the monastery as a novice to become a Lama.

Besides such lifetime devotees, the other members of the Monpa family though were free to lead the domestic life have been found to partly devote themselves to the day to day service in the monastery. Such works are performed by the people most willingly with a degree of pride and prestige. The notion behind was to be closer to the Supreme Being. The people even today voluntarily donate whatever is possible on their part towards the monastery to help continue with the daily affairs and for the upkeep of the Lamas. It requires to be stated that the Pangchenpas (Monpas) of Zemithang Circle happily donate yak’s butter for lighting the butter lamps and other ritualistic purposes to the monastery as they are pure transhumant shepherds and do not do any cultivation due to infertile soil.

Apart from monasteries there are two nunneries at Tawang. The inmates of the nunnery which is known as the Pramo Dongzung Ane Gompa depend totally, even today, on the charity of the laity for their upkeep and this nunnery situated nine kilometres to the north of the Tawang monastery. The other nunnery is known as the Giangong Ane Gompa, situated five kilometres north of the Tawang monastery. The inmates of this nunnery are however scheduled to draw a fixed monthly allowance of either food grains or cash from the Tawang monastery.

Changing Face of Monastic Education

It was after 1962 with the establishment of the modern infrastructure and road connectivity with rest of India through the state of Assam and with the entry of pan-Indian population that facilitated the entry of the modern and Western elements in the socio-cultural life of the people the notion of betterment of life has totally changed. The traditional rigidity towards religion for which the Monpas were known has been loosened to some extent as a consequence of faster life and modern engagements.

A slackening of obligation is thus noticed towards the monastery at Tawang except on personal problems. Traditional monastic education also received an appreciable jolt with the advent of modernization in the Monpa country. This is evident and significant in the people’s liking in the West oriented formal education in place of the traditional monastic one. Nevertheless, one should not think that monastic education has been totally abolished. Even today there are trainee Lamas admitted in the Tawang monastery. It however is important to note that under no circumstances the Monpas have given up their faith in Buddhism but it seems to be a practical thinking on their part to attach importance towards material growth after so many centuries of subjugation under the alien rulers that never allowed them freedom of progress and betterment.

Today, as has been told all the Lamas in the Tawang monastery are the Monpas and they keep the requests made by the laity to visit their houses to perform pujas in case the devotees have personal problems or sickness. It has been observed at present that most of the visitors in the monastery are tourists from the pan-Indian region. Nevertheless, the Monpas of Tawang and others from the fur-flung areas assemble in the courtyard of the monastery during the important annual religious functions such as Losar,Torgya (Plate 9), Saga Dawa, DukpaTse-Shi, Lhabab Duechen, etc.

Frequently Asked Questions about Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh:

Q. Where is Tawang located?

A: Tawang is a district located in the westernmost part of Arunachal Pradesh, a state in northeastern India. It shares borders with the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) to the north and Bhutan to the west and south. The district of West Kameng lies to its east.

Q. What is the historical significance of Tawang?

A: Tawang has a rich historical significance. It was an ancient caravan trade route that connected the Tibetan plateau with the plains of Assam. In the 17th century, the Tawang Monastery, an important Tibetan-Lamaist Buddhist monastery, was constructed, making Tawang a significant Buddhist pilgrimage site for the Monpas and people from around the world.

Q. Who are the Monpas?

A: The Monpas are the dominant tribe in Tawang and the neighboring district of West Kameng. They have a long history in the region, dating back to 500 BC to 600 AD when the kingdom of Lhomon or Monyul ruled the area. Over time, the Monpas became followers of Tibetan Buddhism.

Q. What is the legend behind the construction of the Tawang Monastery?

A; According to legend, Mera Lama, who hailed from the village of Mera near Tawang, was assigned a mission by the 5th Dalai Lama to find a suitable location for a monastery in Tawang. After a long search, he found his horse grazing on a flat mountaintop, which he interpreted as a divine sign. With the help of the local people, he built the Tawang Monastery in 1681.

Q. What is the structural significance of the Tawang Monastery?

A: The Tawang Monastery is situated on a high cliff and has a large campus with Tibetan-style buildings. It was strategically built to be naturally secured from the southern and western sides by steep gorges, making it difficult for anyone to climb. The monastery can only be accessed from the north along a ridge, and it served as a military post against potential hostilities.

Q. How did Tawang come under Indian administration?

A: In 1951, Major Ralengnao (Bob) Khathing, an officer in the Assam Rifles, led a retinue and annexed Tawang, bringing it under Indian control. This action was taken to solidify Indian administration in the region. Prior to that, Tawang had been under the control of Tibet, and the Tibetan monastery officials were collecting taxes from the local population.

Q. How did the presence of Tibetans in Tawang affect the Monpas?

A: The Tibetans, in the guise of ecclesiastic rulers, exploited the simplicity of the Monpas for centuries. The Monpas, being devout and trusting, allowed the Tibetan rulers to collect taxes and make significant contributions to the Tawang Monastery. The British-Indian colonial government, indecisive in taking over Tawang, provided an opportunity for Tibetan administrators to continue their exploitative activities.

Q. What was the significance of the 1914 Simla Accord?

A: The 1914 Simla Accord established the McMahon Line as the new border between British India and Tibet. As per the accord, Tibet relinquished some territory, including Tawang, to the British. However, the British did not take immediate possession of Tawang, and Tibetans remained in control of the area.

Q. How has modernization affected Tawang and its monastery?

A: Since the 1960s, with the establishment of modern infrastructure and road connectivity, Tawang has experienced modernization and Western influences. Traditional monastic education has declined, and formal education has become more popular among the Monpas. However, Buddhism remains an important aspect of their lives, and the Tawang Monastery continues to attract tourists and host important religious functions.