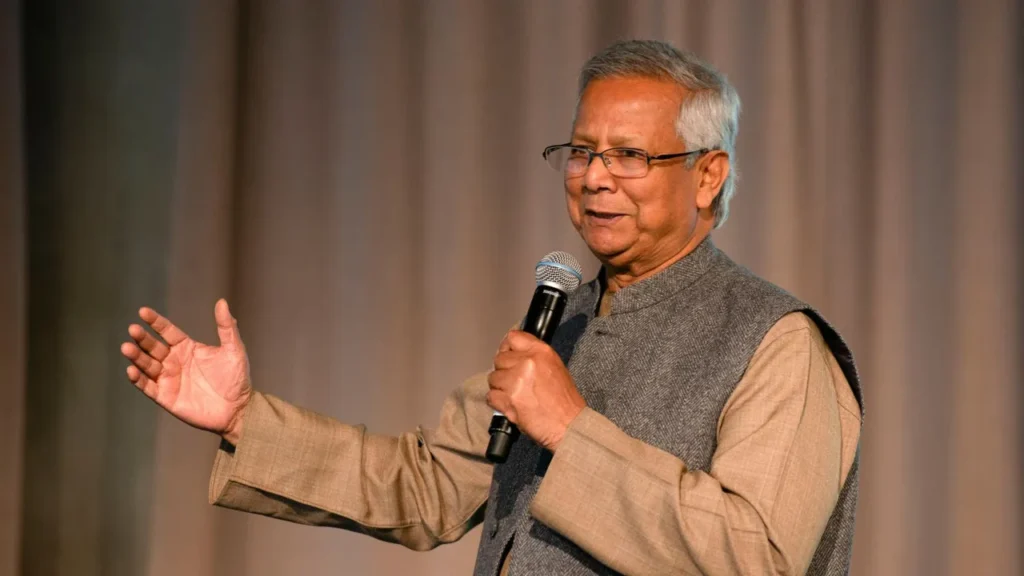

The Chief Adviser of Bangladesh’s interim government, Professor Muhammad Yunus, has once again stirred diplomatic unease by treading uninvited into India’s sovereign domain. His latest remarks, made during a courtesy meeting with Nepal’s Deputy Speaker in Dhaka, went beyond diplomatic overreach—this time invoking India’s Northeast as part of an integrated economic plan involving Bangladesh, Nepal, and Bhutan. What may seem like a harmless vision of regional cooperation is, in reality, a pattern of calculated rhetoric that increasingly casts doubt over Yunus’s intentions. His casual and repeated references to India’s northeastern states in foreign engagements—without prior consultation with India—are not only inappropriate but fraught with serious implications for regional stability and mutual trust.

While regional cooperation is a laudable goal, Yunus’s framing of the proposal is far from benign. He did not merely highlight economic potential; he once again dragged India’s sensitive North East into his vision for a transnational alliance—without any prior consultations with New Delhi, and more disturbingly, in a manner that challenges India’s territorial sanctity. By choosing to invoke the “Seven Sisters” of India in a bilateral discussion with Nepal, and by projecting Bangladesh as a natural regional hub or even as a geopolitical guardian, Yunus is setting a dangerous precedent that goes beyond diplomacy—it hints at strategic manipulation and covert attempts to alter the regional status quo.

This is not an isolated misstep. It is part of a growing pattern. In April, during his visit to China, Yunus had made similarly provocative comments, calling India’s Northeast “landlocked” and declaring Bangladesh as the “only guardian of the Ocean” for the region—an unmistakable overture to Beijing for economic and possibly strategic cooperation. This language not only infringes upon India’s sovereign space but also signals to external powers that Bangladesh may be willing to allow or even facilitate deeper Chinese access to the Bay of Bengal, under the guise of regional development.

The growing unease is not without basis. Bangladesh’s interim regime has been increasingly entangled in narratives that are not just inflammatory but border on strategic incitement. Not long ago, Major General (Retd) A.L.M. Fazlur Rahman, a senior member of the interim government, made an outrageous and deeply alarming suggestion that Bangladesh should “occupy the seven states of Northeast India” with China’s backing if India were to initiate military action against Pakistan. Such incendiary remarks—posted casually on Facebook—may seem fringe or rhetorical on the surface, but they point to a disturbing undercurrent in the interim regime’s political thinking. It echoes a long-buried irredentist tendency now wrapped in the language of strategic defiance.

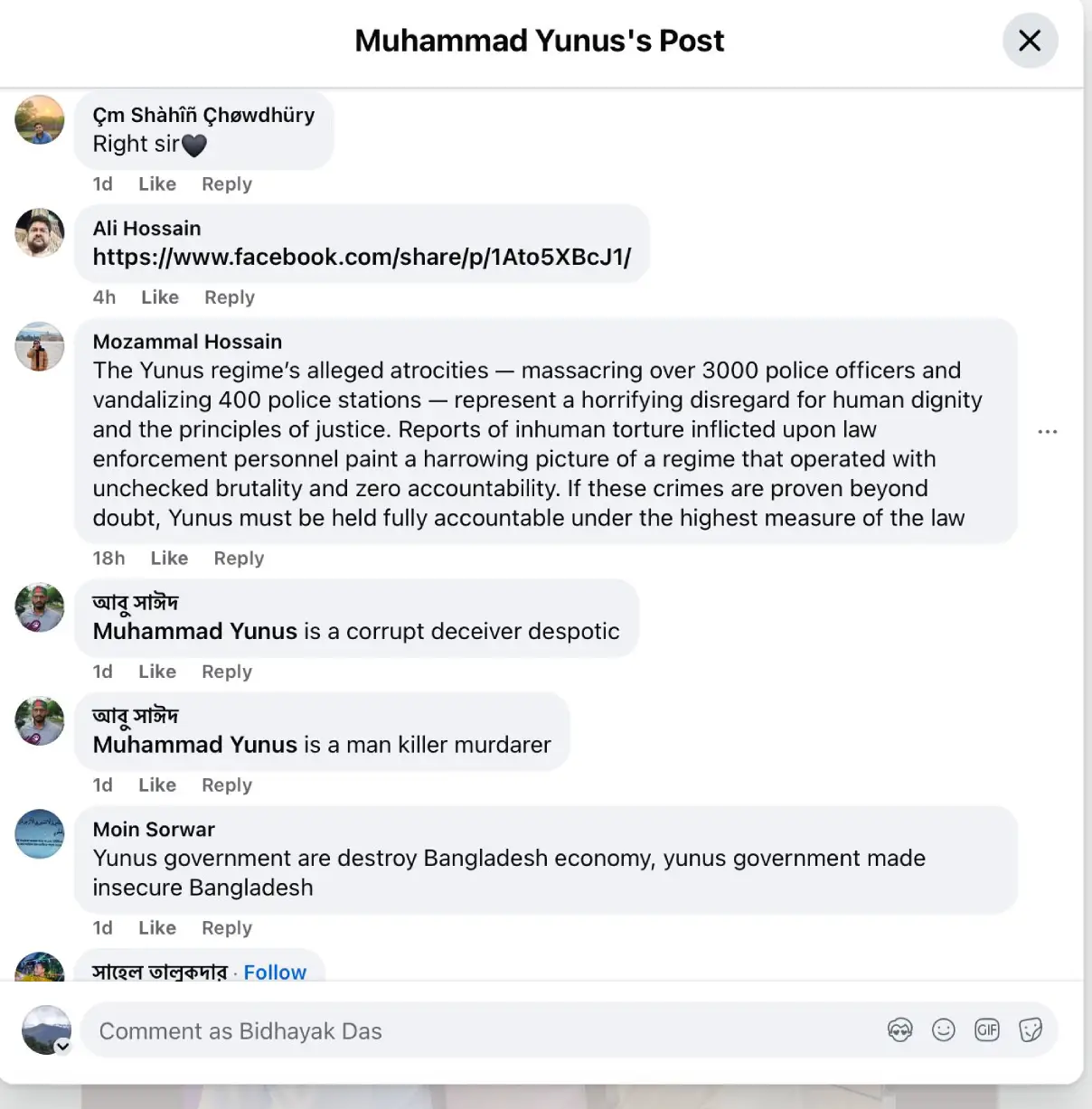

Yunus’s statements have already triggered backlash within Bangladesh and abroad. A particularly scathing response came from one Mozammal Hossain, reacting on Facebook to Yunus’s post about the Nepal meeting. He wrote:

“The Yunus regime’s alleged atrocities—massacring over 3,000 police officers and vandalizing 400 police stations—represent a horrifying disregard for human dignity and the principles of justice. Reports of inhuman torture inflicted upon law enforcement personnel paint a harrowing picture of a regime that operated with unchecked brutality and zero accountability. If these crimes are proven beyond doubt, Yunus must be held fully accountable under the highest measure of the law.”

But the disquiet is not just internal. After Yunus’s remarks in China, Indian leaders from across the political spectrum spoke up. Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma condemned Yunus’s statements as “offensive” and “strongly condemnable.” Economist and BJP ideologue Sanjeev Sanyal publicly questioned Yunus’s claim of Northeast India being dependent on Bangladesh as its only maritime outlet, calling it misleading and problematic. Congress leader Pawan Khera also chimed in, calling Yunus’s approach “dangerous” for India’s Northeast and demanded clarity on the Indian government’s diplomatic posture.

This time around, while New Delhi has not issued an official response yet, sources suggest that a firm message to Dhaka is imminent. And, in the aftermath of India’s decisive Operation Sindoor and Prime Minister Modi’s recent warnings, insiders hint that New Delhi’s patience is wearing thin. “Dealings with Bangladesh will now be different,” said one government source, underscoring a growing perception that Yunus’s consistent references to Northeast India in strategic dialogues with other countries is not merely undiplomatic, but potentially hostile.

Yunus, in his latest conversation, continued to push his line by proposing deeper cooperation between Bangladesh, Nepal, and Bhutan in energy and infrastructure. He cited the Bangladesh-Nepal-India Tripartite Power Sales Agreement, signed in October, under which 40MW of power would be transmitted from Nepal to Bangladesh using India’s transmission lines. “There should be an integrated economic plan for Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Seven Sisters,” he insisted. He also mentioned the construction of a 1,000-bed hospital in Rangpur, which he said would be open to patients from Nepal and Bhutan, as a symbol of “regional health security.”

There is, in theory, nothing wrong with cross-border healthcare or power cooperation. But Yunus’s insistence on unilaterally including Northeast India into a regional framework—without India’s consent—is precisely what makes his proposals alarming. Worse still, Yunus seems to be ignoring the reality that over 90% of Bangladeshis themselves come to India for medical treatment, not the other way around. India, not Bangladesh, has long been the preferred destination for patients from Nepal and Bhutan, owing to both affordability and the high standards of treatment available. To suggest that Bangladesh would serve as a regional healthcare hub is not only premature but also an audacious attempt to reposition regional hierarchies in an artificially favourable light.

What makes this narrative more disturbing is Yunus’s growing proximity to Washington. His elevation to the helm of the interim government is widely believed to have been orchestrated with strong backing from the US. Observers have linked his tenure to the broader American agenda of reshaping regional geopolitics under the guise of humanitarian engagement. This includes plans for opening a “humanitarian corridor” to Myanmar’s Rakhine state—allegedly to support the Rohingya population, but suspected by many to be a cover for increased US presence in the area. Such moves, if true, are less about altruism and more about strategic footholds—potentially providing the US with access to areas bordering the Bay of Bengal and the Chinese sphere of influence.

Central to this theory is the long-standing American interest in St. Martin’s Island, a strategically located territory near the southeastern tip of Bangladesh. It is no secret that the US has made multiple overtures over the years to gain access to the island—allegedly for surveillance or staging purposes—given its proximity to key maritime routes. Former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina had repeatedly rejected such proposals, firmly asserting Bangladesh’s sovereignty and strategic independence. Yunus, by contrast, appears far more pliable. His readiness to engage with the US on sensitive regional issues and his openness to shaping regional policies without involving India suggest a potential realignment of Dhaka’s geopolitical loyalties.

Domestically, Yunus faces increasing scrutiny over his government’s direction. Since the ouster of Sheikh Hasina on August 5, the interim administration has yet to offer a coherent path forward. Its strained relationship with the Bangladeshi military and increasing reliance on Islamist groups paint a troubling picture of a regime that may be more concerned with holding on to power than reforming governance. Yunus’s provocative statements, whether strategic or politically motivated, are not merely rhetorical flourishes—they underscore the fragile geopolitical reality of the region and the willingness of certain actors to exploit it.

Ultimately, Professor Yunus’s repeated invocation of India’s Northeast—without consent, coordination, or caution—represents a thinly veiled attempt to manipulate regional dynamics and assert influence beyond his legitimate scope. His actions are not just diplomatically reckless; they are dangerous and disrespectful to the sovereignty of a neighbouring country. As India watches closely, and as tensions ripple across the region, one question looms large: Is Yunus charting a path toward regional cooperation—or sowing the seeds of deeper instability under the guise of visionary leadership? The answer, increasingly, appears to lie in the latter.