The Tai Khamti dance dramas known as Ka Pung are markers of an advanced culture of the Tai Khamti tribe of Northeast India. The word Ka Pung literally means dance-story, where Ka is dance and Pung is story. Performed during Samkyen also known as the water splashing festival, and observed in mainland Southeast Asia and Buddhist festivals like Khamsang and Potwah, Ka Pung’s main purpose is to give moral lessons besides entertaining patrons.

Focussing on the performative culture of the Khamtis, this article discusses the dance dramas of the Tai Khamti and explicating different facets of Ka Pung Tai, the author argues how it represents a pan-Asian culture and is a confluence of Mahayana and Hinayana schools of Buddhism.

An unique genre

Ka Pung or Ka Pung Tai is a unique performing arts form practised by the Tai Khamti. The Tai Khamtis are a Buddhist tribe of Shan descent that migrated from Khamti-mung (mung means land) or Khamti-long (long means a drum) in Northern Burma to Assam in the mid-eighteenth century. They are mainly concentrated in the Namsai District of Arunachal Pradesh and Lakhimpur District of Assam states of India’s North-East.

Ka Pung or dance drama, incorporates different art forms into one, like song, dance, classical literature into one. Pung (drama) and Ka (dance) may also be staged separately. Pung or Khamti drama is written by a playwright in the Khamti language and script. Its main purpose is to convey the noble teachings of Buddha among the masses to lead a righteous life as shown by Buddha in his former births.

The Pung is kind of melodrama in narrative song with dance interspersed to the accompaniment of orchestral music and farce thrown in, lasting for hours, even for whole nights. All important literary works of the Khampti’s including songs or verses for dramatic performances known as Kham Poong are compiled in scholarly poetic and rhyme style. They are rich in consonance and in alliteration. The inner-lying quality of the songs can be only gathered if the listener adjusts himself with the very spirit and soul of the works.

Although it is not known as to date of institution of Pung came, it is traditionally believed that when the Tai Khamti came under the influence of pure Theravada form of Buddhism in the Third Century A.D, that Pung which alludes to past life of persons was conceptualised.

The themes of the Pung- the all-in-one melodrama- are usually based on Jataka tales- the stories of Buddha’s former births, the legendary stories of the epics Ramayana and the Mahabharata, events in the lives of heroic figures of the sixteen Janapadas of ancient India, of great philosopher Leo-Tse-Yun and legendary personages like Chou Mahosadha of China. Although the Pung is usually a portrayal of legends with religious and historical touch in one form or the other, it always provides occasions for great amusements, for many of the narrative songs of the actors and actresses are unorthodox.

Most Pung contain witticism, banter and humour with occasional touching reference to the interesting incidents in the day-to-day lives of men and women which amuse the audience. Besides, there is pantomime as a part of the play and mimic scene to provide refreshing and amusing interludes.

The socio-religious ceremonies and festivals are the occasions for the performance of Pung.

Pung is not performed in any regular theatre or play-house; it is performed in a temporary structure with a large roof supported by poles and open at the sides. In the middle of it an arena-like open space and is made with a pole decked with leaves and flowers in the centre, which makes the stage. Actors and actresses perform the play on it, usually going round the centre-pole while in action. At one corner of this open space is the orchestra that sits on the floor, while the spectators—also on the floor—sit along the sides of the stage like a theatre-in-the-round.

The costumes worn by the performers are elaborately designed. The use of masks by performers representing animals, ogres and dragons is a distinctive feature of the Pung. However, these masks and attires are not intended to make these ‘beings’, look life-like and true to the nature. Use of masks in a Pung is purely conventional and a customary device so that the performers are readily recognized for the characters they represent than dramatically conceived.

The masks and the attires used in Pung were earlier made by the Khamti’s themselves.

Since, Pung is essentially a melodrama, all the performers must be singers and dancers for their roles. Dialogues are sung after the songs and performers dance to the music played by the orchestra. Songs employed in the Pung are of two types, viz. the melodious and the other type is the tenor voice accompanied by a sombre tune. Characters in principal role like the heroes and heroines, gods, royal personages generally sing the melodious tune; the other characters sing the songs in tenor voice. This division is for the style and to suit the roles, not for the qualities of the songs. Various types of dances are performed in the Pung that can be roughly categorized into four main forms viz. majestic-dance, quick-dance, character-dance and action-dance.

Thus, Pung manifests a highly evolved performance, putting together multiple art forms. It also incorporates classical literature and history. Though, influenced by Buddhism, the dresses and styles of Pung exhibit traditional Tai characteristic and are unique and distinct from other Indian art forms.

Ka Pung and Khamti identity

Identity refers to sameness of essential or generic character in different instances. Identity could also mean, the characteristics determining who or what a person or thing is. As per these dictionary definitions, character or characteristics of a person or a thing or commonness of characteristics is highlighted while defining identity. So how the Ka Pung does exhibit and reinforce the Tai Khamti cultural identity?

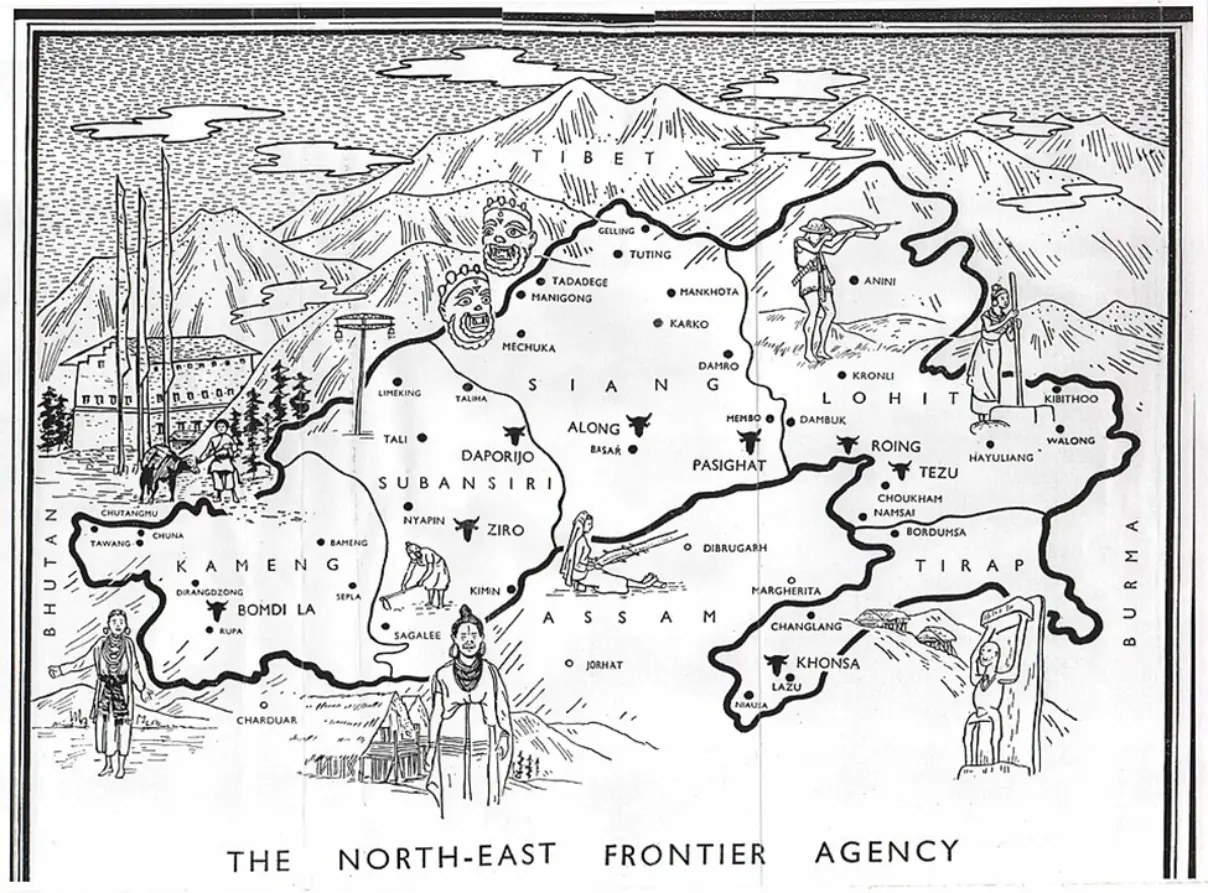

Verrier Elwin in the book Art of The North-East Frontier of India divides the tract of the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) administration that is present-day Northeastern state of Arunachal Pradesh into three main artistic and cultural provinces. The people of the first are Buddhist by religion and include the Sherdukpens and Monpas of the western part of Kameng and to some extent Bugun, Aka and Dhammai groups who are in close contact with them and have come under their influence. With them the Tibetan-speaking Membas and Khambas in Lohit division also could be included in this category.

Elwin writes, “Although the artistic tradition of the Khamtis and Singhpos has taken a different course and they are geographically isolated from the border groups, they could be included here (i.e. in the first category), for they are Buddhist in religion and have certain characteristics in common, such as the making of masks, which are unknown elsewhere in NEFA.”

The second cultural area stretches from West to East, from Sepla in Kameng and through the greater part of Subansiri, Siang and Lohit districts. These tribes are more akin to weaving and fine work in cane and bamboo, however are marked by near absence of wood carving. The Third cultural area is to the south-east of NEFA where the Nochtes, who are Vaishnavite by religion, the Wangchos, Tangsas, all of whom derive their influence from Burma.

Thus, Elwin employs religion is a defining characteristic on the basis of which their cultural and artistic identity has been classified. It is important to understand how the performing arts traditions of the Buddhist tribes living in Eastern Arunachal Pradesh (Khamtis and Singhpos) and Western Arunachal Pradesh (Monpas, Khambas and Sherdukpens) share similar traits.

Pantomime is part of the performing arts of the tribes inhabited in the Mon cultural zone of Arunachal Pradesh, whom Elwin classifies in the first category. They are Vajrayana Buddhists or followers of the Tibetan school of Buddhism. Monpas and Sherdukpens have several pantomimes depicting some legendary stories or events. Colorful masks are prepared for the pantomimes. Their dances are staged during religious festivals like Chokor, Chosiwang and Tonuwang and the Monpa pantomimes and also during the New Year festival, Losar. Drums and cymbals are played as music. The pantomimes are staged in front of the temple or at some central convenient place. The Sherdukpen pantomimes are Jiji- Sukham or Yak pantomime, ajjmalu pantomime, Jikcham or deer pantomime, Jachungcham or bird pantomime etc.

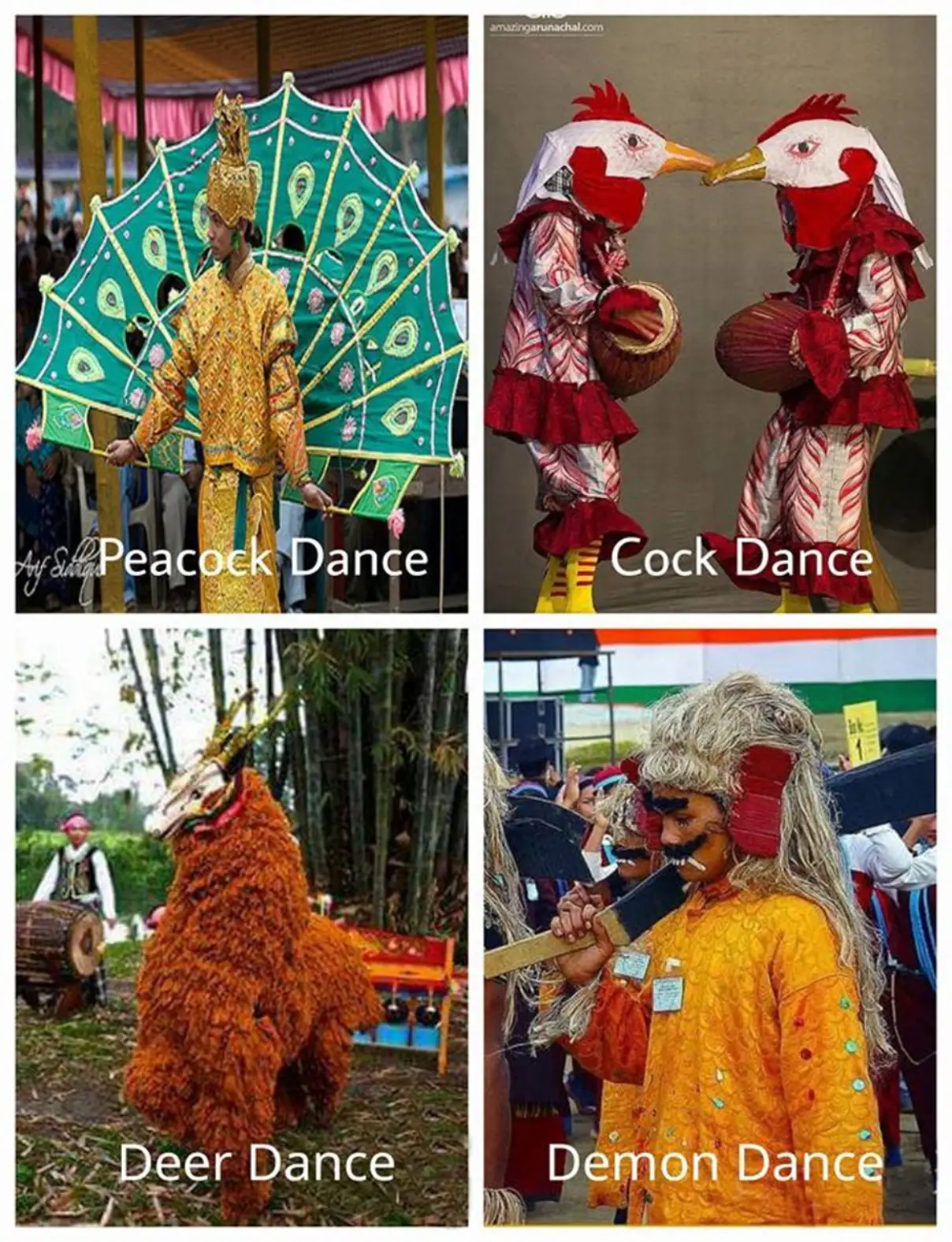

Pantomimes are an intrinsic part of Ka- the Tai Khamtis dances. The Peacock Dance, also known as Kaa Kingnara Kingnari depicts Buddhistic belief in nature which depict the slow and gracious dance of mythical half human and half peacock that existed in the Himalayas. The Cock Fight Dance- Kaa Kong Tou Kai performed by two or four people who wear a head gear shaped like the head of the cock and inspired by the ancient tradition of entertaining the king with a cock fight.

The Khamti in their ceremonial dances use embossed shields and masks, mainly of the horror type- made up of coloured cloth and stretched on bamboo. The dances mainly illustrate the templation of the Lord Buddha and other themes.

Deer Dance known as Kaa-Toe held in the month of October is a celebration of the light festival based on the story of the spirits of the people and animals welcoming the return of Buddha after his preaching and thanks giving to his mother and other spirit in spiritual world. This dancing of Ka-Toe is in fact a Buddhist belief and religious in nature.

The demon dance Kaa Phi Phai in Khamti language is another prominent dance and is performed on important social and religious occasions. The theme of this dance revolves around the attainment of the enlightenment by Lord Buddha despite attempts of ‘Mara’, the king of evil spirits to disturb deep meditation of the Lord. Kaa Phi Phai symbolizes the victory of the holy over the evil and marks the Buddha’s attainment of ‘Nirvana’.

We can hereby infer that despite being from different schools of Buddhism, the Tai Khamti following the Theravada school and the tribes living in Western Arunachal Pradesh have the pantomime form and use of masks in their dances, in common with each other. Understandably, the Sherdukpens and Monpas have a Vajrayana connection, but how come, Tai Khamti who follow the Thervada Buddhism and migrated from Burma have similar mask dances. This will be discussed next.

Evidence of Pan-Asian culture

The Tai Khamtis are one of the six Tai ethnic groups living in India. The other Tai groups in India’s North-East are the Tai Ahoms, Tai Khamyangs, Tai Phake, Tai Aiton and Tai Turung. Ramesh Buragohain in his book The Lost Trails-Volume I notes that besides, India’s North-East, the Tai’s are found in several regions of Myanmar, all over Thailand and Laos, Northern Vietnam and Southern provinces of China. But the members of this great ethnic group, to whatever local groups they may belong, call themselves Tai, for e.g. Tais are called Thais in Thailand and Laos, Shans in Burma, Dais in China, Ahom, Khamti, Phake, Turungs, Khamyangs and Aitons in India.

Eminent Tai Schcolar Puspadhar Gogoi in his chapter titled- The Tai and Tai Kingdoms in India in Lila Gogoi (ed.) book- The Tai Khamtis of Northeast India writes that the Tai denotes a great branch of the Mongoloid population of Asia. The original place of the Tai was the Kiulung mountains in Mongolia from where the Tai moved to the South following the courses of the Yellow River. They emerged as a distict race in South-west China and in the course of time due to the pressure of the Mongulhoardes they had to move to the South along the courses of the rivers Irrawaddy, Salween, Menam, Mekong and Brahmaputra. The present habitat of the Tai’s are spread out like a vast ocean in the Asiatic hemisphere.

The Tai Khamtis on their migration to Assam in the eighteenth century from Burma had Buddhism as their major religion. Buragohain sic. The Lost Trails Vol-I argues that the Shans of Burma, among whom the Khamtis are a sub-group adopted their present day religious forms in the fourteenth century. He further argues that the Shans of Burma had definate influnce of Mahayana Buddhism. However, Buragohain writes, some scholars have also argued that the Tai-Yi as the Shans are known prior to their arrival to Shan land were animists and some of them imbibed the tenets of Taoism and Mahayana docrtines.

Influence of Mahayan Buddhism on the Shans who only in the 14th century are said to have taken to Theravada Buddhism, explains the commoness of Khamti of masks and pantomime form of their dances with the Monpas and Sherdukpens. Besides, being fond of masks the Khamtis also are good at wood-carving and are skilled in weaving and emroidery. These crafts can also likely be traced to their pre-Theravadin influence.

Another evidence of the Mahayana Buddhism influence is the similarity between the dances performed by the Tai Ahom’s and the other Buddhist Tai’s (and the Khamtis in particular). The Ahom’s migrated to Assam in the 13th century from Burma were at the crossroads of religious culture as their religion had a blend of Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism and Hinduism like the Tai culture upto the 14th century A.D.

Chao Pushpa Gogoi in his seminal book- The Tai’s of North-East India argues that despite the dances of the Buddhist Tai’s are related to Buddhism, the dresses and style are traditional Tai and not influenced by Indian dances at all. The Peacock dance that is also found among the Tai Khamti is common with the Tai’s of South East Asia.

Gogoi further states that the basic principles of the Tai dances (Ka Tai) of all the Tai’s is the same, rhythm and postures. He argues that the body postures do not vary very much from each other. Gogoi underlines that the movements of the body are alost gentle and sobre and give a soft feeling in the mind. In some dances, the body movements are slower at the beginning and then develop into faster movements and the climax is reached, he adds. Music is accompanied in some dances, the Tai scholar explains. Disscuing the songs and music accompanied by Tai dances, Gogoi points out the striking similarlity between the Buddhist Tai’s and the Tai Ahoms.Buddhist Tai’s use drums and gongs as accompaniments with the dances. The Tai Ahoms use different kinds of drums and they are more in number than the other Tai’s. Some Khamtis and Aitons use drums used by the Ahoms. Specially, the short-drum used by the Ahoms is also used by the Khamtis in the dance Ka Kong Tu Kai or the Cock-fight dance.

Intangibile cultural heritage

Ka Pung is an intangible cultural heritage of India. It not just artistically rich, bringing together different genres but also is part of the rich Tai cultural heritage that’s spread across three regions- East Asia, South Asia and South-East Asia and depicts a pan-asian culture.

The migration of the Tai Khamtis from Bor Khamti in Myanmar along with other five other Buddhist tribes saw the reentering of Thervada Buddhism in India’s Northeast in the eighteenth century. Buddhism in India’s Northeast was predominently of Mahayana sect until the immigration from Myanmar of the Tai groups reintroduced Hinayana Buddhism.

J.N. Chowdhury in his book Arunachal Panorama writes like the Mahayana School of Buddhism collectively known as Northern Buddhism entered Tibet from Kashmir in the seventh century and again found its way back into India among the Monpas and Sherdukpens of the Kameng district of Arunachal Pradesh via Bhutan, Thervada Buddhism later called as Southern Buddhism which had originally migrated to Burma from Sri Lanka was carried back to India by the Khamtis and the Singhpos.

The pantomime form and use of masks in Khamti dances despite being ardent followers of Burmese School of the Buddhism, the Tai Khamti culture is a unique blend of the Theravada and Mahayana schools of Buddhism. B.K. Singh in the book- Encyclopaedia of Ai-Tai Khampti rightly points of that the Khamti religion as an amalgamation of Buddhim and indigenous faiths and beliefs, the dual practice of twin faiths and beliefs in their religious and cultural lives. They observe the principles of Buddhism simultanously with their indigenous faiths and beliefs, so inspite of clashing with each other, this amalgamation provides a new and peculiar phenomena which ultimately beautifies and decorates their whole culture, he submits.

This harmonious synthesis demonstrates how cultural identity can transcend rigid religious boundaries, creating a living tradition that honors both ancient wisdom and local heritage. The Khamti example thus serves as a compelling model of how diverse spiritual practices can coexist and mutually enrich one another within a single cultural framework.