The road from Phuentsholing to Thimphu begins as a ribbon of tarmac clinging to the Himalayan foothills, winding past mist-veiled slopes and rushing mountain streams. Trucks and taxis jostle for space with monastery-bound monks in crimson robes, their prayer beads moving as steadily as the wheels. With each turn, the air grows crisper, the chatter of the plains fading into the quiet dignity of a mountain kingdom.

For the casual traveller, it is a scenic six-hour journey into Bhutan’s serene heart. But for those attuned to the undercurrents of the Himalayas, this is more than a drive — it is an entry into one of Asia’s most delicate geopolitical balancing acts. Every bend carries echoes of history, every valley hides the weight of a centuries-old friendship with India, and every ridgeline hints at the shadow of China beyond the high passes.

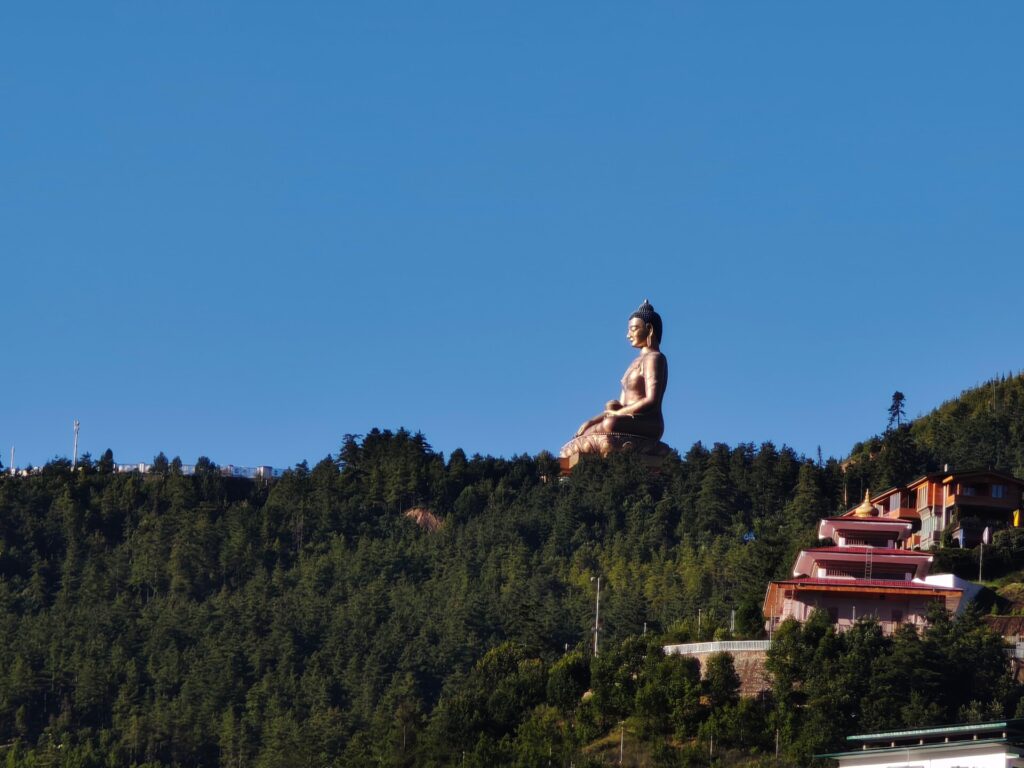

Where beauty meets strategy

Bhutan’s location is as breathtaking as it is strategic. To the south and west lies India — Sikkim, West Bengal, Assam, and Arunachal Pradesh — while to the north, the mountains meet China’s Tibetan frontier. This proximity makes Bhutan a keystone in India’s security calculus, especially where its western border collides with the geopolitical fault line of the Doklam Plateau.

Doklam is not just a patch of high-altitude pasture; it is the watchtower over the Siliguri Corridor — India’s narrow “Chicken Neck” lifeline to its Northeast. In Thimphu’s eyes, Doklam is indisputably Bhutanese territory. In New Delhi’s, it is also an irreplaceable buffer. Beijing, however, claims it as an extension of the Chumbi Valley and has sought to redraw the tri-junction point seven kilometres south — a shift that would hand China the plateau and bring it dangerously close to India’s vulnerable corridor.

Professor Adwitya Thapa of the Centre for Himalayan Studies puts it plainly: “The road you travel from Phuentsholing to Thimphu is not just a road — it is a reminder of why Bhutan’s relationship with India is unlike any other. Every bridge, every bend, every ridgeline is part of a shared security and a shared future.” His words echo in the hum of the engine as we climb higher, each turn unveiling not just a vista, but also a reality — that Bhutan’s modernisation and its strategic safety net are inseparably tied to New Delhi.

Bhutan’s measured steps on the border issue

Since 1996, China has dangled a “package deal”: surrender Doklam in exchange for two northern valleys, Jakurlung and Pasamlung. Thimphu has resisted, knowing the cost of such a trade is far greater than its face value. Yet the pressure persists.

The 25th round of Bhutan–China boundary talks in October 2023, marked by former Bhutanese Foreign Minister Tandi Dorji’s visit to Beijing, signalled renewed momentum in negotiations. For India, the stakes were unmistakable: any shift in control over Doklam could tilt the regional balance. The 2017 standoff — when Indian troops blocked Chinese road construction there — remains a reminder of how swiftly tensions can flare.

In Bhutan’s capital, the tone is careful. Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay emphasises that dealings with China are “confined to only boundary demarcations.” His message is deliberate: the talks may continue, but India will never be blindsided.

A visit to Doklam — whether from the Sikkim side of the border or from Haa in western Bhutan, where the Indian Military Training Team (IMTRAT) headquarters is located — brings into focus the strategic importance of the plateau on the southeast side of the tri-junction. Experts argue that Bhutanese control over Doklam gives India a significant advantage against China, allowing it to mount strategic offensive and counteroffensive manoeuvres from Sikkim.

Chinese control, however, would enable a military push down the Chumbi Valley, potentially severing India’s overland link to its Northeast. The valley’s narrowness makes such manoeuvres challenging, which is why Beijing seeks to extend it by incorporating Doklam. The 2017 standoff, triggered by Chinese road-building, underscored this danger. In response, India has strengthened its presence through IMTRAT, built strategic roads, and provided weapons and training to Bhutan.

Bhutan, for its part, has resisted Beijing’s offers despite persistent pressure, fully aware that Doklam’s fate is intertwined with India–China relations. Any settlement will be shaped not only by Bhutan’s diplomacy but also by how the two larger neighbours manage their own disputes — particularly in Arunachal Pradesh.

China’s long game

For Beijing, the Bhutan border question is part of a wider strategic chessboard. The 764 sq km of disputed territory — 269 sq km in Doklam, 495 sq km in the northern valleys — is bound up with China’s claims over Arunachal Pradesh and its push to dominate key Himalayan passes.

China has employed multiple tactics: offering economic incentives, pressing for formal diplomatic ties, and linking those ties to a possible border settlement. According to reports published in the media Beijing is willing to relinquish claims on Jakurlung and Pasamlung Valleys only if Bhutan establishes formal relations and trade with China — a quid pro quo that would fundamentally alter Bhutan’s foreign policy posture.

At the same time, China has undermined the 1998 agreement to maintain the status quo by building settlements inside Bhutanese territory in the north. These moves, coupled with examples from other countries where Chinese investments have led to economic and political dependency, have deepened scepticism in Bhutan.

While a small section of Bhutan’s elite argues for “self-dependence” and the benefits of engaging China directly, the overwhelming sentiment — particularly among those who recall India’s role in safeguarding Bhutan’s sovereignty — remains firmly pro-India. Diplomatic patterns reinforce this: after each round of boundary talks with China, Bhutan’s King or senior leaders make a point of visiting India soon after, signalling transparency and alignment.

For instance, shortly after the October 2023 talks in Beijing, King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck travelled to India to meet Prime Minister Narendra Modi and External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar — a clear indication that Thimphu was keeping New Delhi closely informed, even if no public details emerged from the talks.

Signals of assurance

What stood out during the Prime Minister’s interaction was not just the content of his words but the deliberate choice of language. Tshering Tobgay did not lean on the familiar diplomatic vocabulary of “partnership,” “bilateral ties,” or “mutual interest.” Instead, he repeatedly used the word “friend,” underscoring that Bhutan’s relationship with India is “not just a relationship” but “a friendship.”

In the Himalayan political context, such a choice is deliberate. Words here are not ornamental; they are signals. “Friendship” conveys intimacy and trust, cutting through the transactional language of statecraft. It draws on shared memory — of Indian support during Bhutan’s first steps into modern governance, of crisis cooperation during border tensions, and of countless small acts of solidarity that have woven the two nations’ fates together.

This framing carries strategic weight. It tells New Delhi that Bhutan intends to keep India fully in the loop on sensitive border talks with China. It warns Beijing that any agreement touching India’s security red lines is non-negotiable. And it reassures Bhutan’s citizens that no deal will compromise sovereignty or leave the country exposed to coercion.

As Professor Thapa observed, Prime Minister Tobgay’s tone and body language radiated “an assurance” that Bhutan’s engagement with China would remain “extra cautious.” This assurance was not simply about today’s negotiations but about Bhutan’s posture in the years to come — that it will move slowly, keep its allies close, and treat its security as indivisible from that of India.

Friendship as foundation

If “Signals of assurance” was about words, “Friendship as foundation” is about proof — decades of lived reality that explain why those words ring true. Since 1961, when Bhutan first embarked on its planned development, India has been its principal partner in building the material and institutional backbone of the kingdom.

The “unreserved and unconditional support” that Tobgay acknowledged is visible in every major road cutting across the mountains, every school and hospital serving remote valleys, and in the hydropower projects that form the heart of Bhutan’s economy.

This foundation is not merely economic; it is existential. In a region where the lure of quick development loans often comes with strategic strings, Bhutan has avoided the pitfalls that have ensnared some of its neighbours. The reason lies in trust — a trust built through decades in which Indian assistance has come without undermining Bhutan’s sovereignty or demanding political concessions.

The material side of this foundation is formidable. As confirmed by Bhutanese Prime Minister Tobgay, India’s contribution to Bhutan’s 13th Five Year Plan stands at ₹8,500 crore, with an additional ₹1,500 crore for post-pandemic recovery. These funds have translated into strategic roads, hydropower plants, and social infrastructure, giving Bhutan the resilience to withstand external pressures, including those from China.

Partnership in action

Bhutan’s hydropower sector remains the most visible example of this partnership. India has built four major projects — Chukha, Kurichhu, Tala, and Mangdechhu — and is completing Punatsangchhu-I and II. The 120 MW Punatsangchhu Hydro Project is ready for launch.

These projects power Bhutan’s economy and export clean energy to India, creating a mutually beneficial loop. Prime Minister Tobgay informed that the partnership is widening to include private Indian players like Tata Power, Adani, and Reliance, signalling a shift from purely state-led cooperation to a broader commercial model.

In March 2024, the two countries signed a Joint Vision Document on the India–Bhutan Energy Partnership, with an eye on powering the Gelephu Mindfulness City — a flagship Bhutanese project rooted in Vajrayana Buddhist principles and designed as a hub of sustainable urbanism.

Cooperation now spans roads, digital networks, and space, including the 2022 launch of the India–Bhutan SAT project. Trade has tripled since 2014–15, and India has committed over ₹1,700 crore in grants and loans to the Gyalsung Project, which will train Bhutanese youth in skills for nation-building.

The road ahead — friendship shaping the region

For many Bhutanese, India is not merely a neighbour but a trusted partner whose presence is woven into the fabric of their nation-building. Even when frustrations arise over infrastructure delays or slow reforms, the instinct is to look southwards before elsewhere.

Bhutan’s careful diplomacy will rest on this foundation as it navigates modernisation, economic growth, and the pressures of an assertive China. For India, the task is to remain a consistent, reliable anchor — delivering projects on time, expanding cooperation, and supporting Bhutan’s connectivity goals in ways that bind its future closer to India and the wider region.

The stakes go beyond bilateral trade and projects. This relationship stabilises the eastern Himalayas, protects the Siliguri Corridor, and offers a counterweight to coercive diplomacy in South Asia. By keeping India closely informed on China negotiations, Bhutan strengthens not only its own position but also the regional security fabric.

On the road back from Thimphu, as mist curled over the ridgelines and strings of prayer flags danced in the mountain wind, it became clear that this “friendship” is not a relic of shared history but a living pact — one that safeguards borders, fuels growth, and preserves Bhutan’s ability to modernise without losing itself. In a neighbourhood where alliances shift with the winds, the India–Bhutan partnership endures — steady, strategic, and deeply human.