In his 2025 Independence Day speech from the Red Fort, Prime Minister Narendra Modi introduced the Demographic Stabilisation Mission(High-Powered Demography Mission), labeling illegal immigration as a deliberate attempt to reshape India’s demographic landscape, particularly in Border States. Announced as part of Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s 2024 budget commitments, this mission aims to monitor demographic shifts, curb illegal infiltration, and safeguard indigenous livelihoods and national security. Northeast India, with its porous borders alongside Myanmar and Bangladesh, is a critical focus, especially in states like Manipur, where migration fuels ethnic tensions and violence.

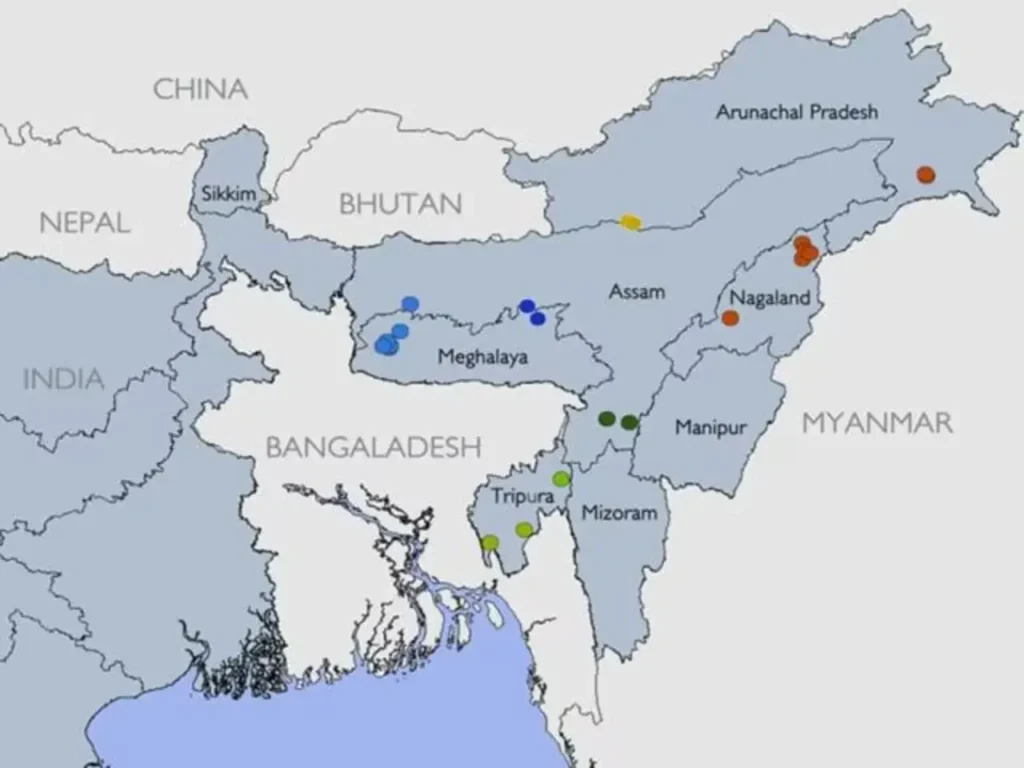

Northeast India’s unique geographic and ethnic diversity makes it highly susceptible to demographic changes. The region, encompassing eight states, shares extensive borders with Myanmar (1,643 km) and Bangladesh (4,096 km), enabling migration driven by economic disparities, political unrest, and kinship networks. Historical migrations, notably post-Partition flows from Bangladesh, have significantly altered demographics in states like Assam and Tripura, raising fears of cultural erosion and resource competition among indigenous groups. In Tripura, census data reveals a drastic decline in the tribal population from approximately 70% in 1901 to under 30% by 1981 due to mass migration, marginalising groups like the Tripuris. Civil society protests in July 2025 demanded robust detection and deportation measures. TipraMotha Party leader Padyot Kishore ManikyaDebbarma noted that Assam, Tripura, and parts of Meghalaya serve as transit hubs for illegal migrants from Bangladesh, with persistent entries despite 90% of Tripura’s 856 km border being fenced. Debbarma stated, “The Indigenous tribes which are asking for land rights here are doing so because we know sooner than later we will be overrun by illegal migration.”

In Assam, the 2019 National Register of Citizens (NRC) excluded approximately 1.9 million individuals from the citizenship list. (However, in Abdul Kuddus v. Union of India (CA 5012 / 2019), affected individuals, alleged to be genuine citizens, can appeal their exclusion from the NRC through Foreigners’ Tribunals, with further recourse to higher courts. This process, governed by the Citizenship Act, 1955, read with amendments in 1985/86 (inserting Section 6A) and 2003/04 (tightening definitions of illegal migrants and NRC procedures), remains sub-judice in several cases, raising significant human rights concerns including potential statelessness and undue hardship on rightful citizens.

Meghalaya, meanwhile, faces pressures from suspected illegal immigration from Bangladesh (sometimes via neighboring states). These migratory trends (often allegedly involving unauthorised settlement, forged documentation, and enrollment in welfare schemes) are raising concerns about demographic shifts that potentially threaten the socio-cultural and political standing of indigenous groups such as the Khasi and Garo tribes.

The state is viewed as a migration “corridor,” prompting demands for the Inner Line Permit (ILP). Enhanced border checks at places like Byrnihat, supported by police and local groups, have intensified. The North East Students’Organisation (NESO) held sit-ins in 2025, urging detection, deportation, and border sealing. Special task forces conducted 30-day crackdowns on Bangladeshi and Rohingya migrants, with the Hynniewtrep Youth Council (HYC) reporting 900 suspected migrants pushed back in August 2025.

The Demographic Stabilisation Mission aligns with these efforts, promising systematic demographic mapping, legal reforms, and state coordination to tackle infiltration. Modi highlighted threats to youth livelihoods, national security, demographic balance, deforestation, and tribal lands, resonating with regional concerns. In 2025, the government deported or pushed back over 4,000 Bangladeshis. Regional groups like NESO organised protests across the Northeast, opposing asylum for Bangladeshis. However, critics argue these pushbacks violate human rights, and scholars like Sabir Ahamed challenge claims of mass infiltration, citing Assam’s Muslim population growth (0.544% annually from 1951–2011) as driven by natural increase rather than migration.

Manipur, with a population of about 3.2 million, comprises Meiteis/MeitiPangals in the valleys and Naga/Kuki-Zo and others tribes in the hills. The 2023 violence, sparked by a High Court order recommending Scheduled Tribe status for Meiteis, was perceived as threatening hill tribes’ privileges, though local leaders attribute tensions to external influences and narco-trafficking. Migration from Myanmar fleeing the 2021 coup, has heightened anxieties. Assam Rifles Director General Lt. Gen. Vikas Lakhera reported 42,000 individuals crossing from Myanmar into Manipur since December 2024, with biometric data collected for monitoring. Former Chief Minister N. Biren Singh endorsed these measures, noting 5,457 “illegal immigrants” detected in 2023 and stressing the “real and ongoing” influx.

James C. Scott’s The Art of Not Being Governed (2009) offers a lens to understand migration in Northeast India. Scott’s concept of “Zomia” (upland Southeast Asia, including parts of Manipur and Mizoram) as zones of state evasion, where hill peoples deliberately adopt mobile, egalitarian lifestyles to resist lowland state integration. Upland regions including parts of Manipur and Mizoram, describes areas where hill peoples resist state control through mobility and egalitarian practices. In Manipur and Mizoram, migration from Myanmar embodies this evasion extended across modern borders. Migrants from Myanmar, fleeing junta violence, use kinship ties and rugged terrain to cross into India’s undergoverned hills, embodying Scott’s “fugitive communities.” This mobility challenges mechanisms like the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) and ILP, with oral myths and networks acting as “cultural shields.”

This migrations to Manipur, a quintessential Zomian phenomenon as outlined and reflects strategic flight to the hills to evade state oppression. Beginning around the 15th century, with references to “Khongjai” in Manipur’s royal chronicles, these Tibeto-Burman groups migrated in waves, peaking during the 18th-19th century “Great Kuki Exodus” from Myanmar’s Chin Hills and Mizoram’s Lushai Hills. Driven by inter-tribal warfare, famines, and Burmese slave-raiding, they sought refuge in Manipur’s rugged terrains, adopting shifting cultivation and fluid kinship structures to resist incorporation by valley states like the Meitei kingdom or Burmese empires. British colonial policies, as noted in The Great Game East by Bertil Lintner, further shaped this migration by resettling “New Kukis” as buffers against Naga raids, offering land for military service, thus embedding them in Manipur’s hills.

The Meitei-Kuki conflict, erupting on May 3, 2023, underscores Zomia’s tension between hill autonomy and valley state-making. Sparked by a tribal march opposing a court directive to consider Scheduled Tribe status for Meiteis, which could grant them access to hill lands, the violence reflects deep-seated ethnic and resource rivalries. Meiteis accuse Kuki-Zo of illegal immigration and poppy cultivation, while Kukis perceive state policies like the “war on drugs” as eviction tactics. Manipur’s situation is particularly complex, with ethnic clashes since May 2023 claiming over 258 lives and displacing 60,000 people, driven by disputes over land, resources, and tribal status. Scott’s framework highlights Kukis as “fugitive” communities resisting state incorporation, while Lintner’s geopolitical lens points to Myanmar’s instability exacerbating tensions via refugee flows.

Official discourses, including those from Biren Singh and Assam Rifles, frame migration as a security imperative. Singh has linked ethnic violence to “foreign hands,” citing arrests of Myanmar-based insurgents as validation. His social media endorsement of biometric mapping underscores a narrative of vigilance against outsiders, aligning with Modi’s mission to safeguard indigenous rights. Assam Rifles’ role in border monitoring and data sharing with agencies like Aadhaar emphasises containment, distinguishing refugees from infiltrators, though this nuance is often absent in rhetoric. The presence of foreign militants like ZRA and KNO on the soil of Manipur (the leaders of these two armed underground groups are not indigenous people of the state; they are foreigners) creates a haven for illegal migrants from neighbouring Myanmar. And also act as an organised syndicate of illegal migrants to control over the politics, administration, economy of the indigenous tribes like Thadou of Manipur. Since the Myanmar Kuki are also from the Chin-Kuki-Mizo community, it’s difficult to identify them once they have entered Manipur. This led to social disparity and enmity among the community, ex-chief minister observed.

The Manipur Legislative Assembly has re-affirmed the resolution passed by the House on August 5 2022 for the implementation of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) in the state. Biren Singh, on his official X account, wrote, “NRC is crucial for safeguarding the interests of our state and contributing to the greater good of our nation”. Calls for permanent border fencing and ending the Free Movement Regime (FMR) with Myanmar.

The mission signifies a major shift towards the securitisation of migration, framing it as a national security threat rather than solely a humanitarian or economic issue. This approach legitimises stringent state actions, such as; enhanced border control though the completion of border fencing (centre is planning to fence the entire Myanmar border with anti-cut, anti-climb technology to prevent infiltration.) and formalise the end of the Free Movement Regime (FMR), as demanded by states like Manipur. Second, the promise of “systematic demographic mapping” and “legal reforms” implies the creation of a robust apparatus for identifying, detaining, and deporting undocumented immigrants, building on mechanisms like the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and biometric data collection by security forces.Third, this mission could mandates better coordination between central and state agencies, potentially leading to more efficient but also more invasive monitoring of population movements. Forth, centre could reiterated its goal of ensuring secure, crime-free borders by cracking down on crossborder criminal activities, movement of criminals, and smuggling networks.

The Demographic Stabilisation Mission in Northeast India addresses legitimate demographic concerns in border states while navigating complex historical, ethnic, and geopolitical dynamics. Its success hinges on evidence-based, proportionate policies that avoid broad securitisation, which risks stigmatising communities and escalating ethnic tensions. In Manipur, addressing structural drivers (land disputes, economic inequality, and political marginalisation) is essential. Effective stabilisation requires confidence-building measures, transparent grievance redressal, and equitable development to mitigate resource competition, combining proportionate security with political dialogue, and humanitarian protection. Furthermore, effective migration management necessitates context-specific, differentiated approaches. Accurate demographic data helps distinguish economic migrants seeking livelihoods, refugees fleeing persecution or conflict, and armed elements exploiting porous borders. While migrants may require regulation and refugees humanitarian aid, insurgent actors demand strict security responses. Clear categorisation ensures balanced policy, protecting indigenous communities while upholding security and humanitarian obligations.