Reporting from the frontlines has always carried risks, but in Nepal’s recent Gen Z protests the dangers multiplied in startling ways. In a revolt that sought to challenge corruption and entrenched elites, the media—local and foreign alike—found itself under direct assault. Instead of being mere chroniclers of history, journalists became unwilling participants in it: targets of bullets, stones, and arson.

On September 8, as thousands thronged the streets of Kathmandu, four Nepali journalists fell to rubber bullets fired by police. Shyam Shrestha of Kantipur TV, Umesh Karki of Nepal Press, and Dipendra Dhungana of Naya Patrika suffered bullet wounds to their legs and necks. Barsha Shah of Deshsanchar was struck by stones hurled by protesters. Their injuries weren’t isolated incidents. They were symbols of the peril of reporting in a country convulsed by rage and resistance, where the messenger became indistinguishable from the message.

These wounds were not just personal scars but also carried a wider meaning. At the same time, they highlighted the unsafe conditions in which the media was operating, often with no protective gear, no institutional backup, and no guarantee of safety in an environment where perhaps both the police and the protesters saw cameras as threats. What should have been an act of public service—recording the birth pangs of change—became, in effect, an act of self-endangerment.

The escalation was swift and brutal. The very next day, arsonists set fire to the offices of Kantipur Media Group (KMG) and Annapurna Post., two major media outlets of the country. Newsrooms were reduced to rubble, servers destroyed, and broadcasts cut off. The attacks were more than random vandalism; they were deliberate blows against press freedom.

“This is not the first assault the Kantipur Media Group faces. We have already faced 3-4 such attacks though not at this scale. Our assumption is the forces which were not happy with our coverage planned the assault this time. They seem to have targeted us assuming that we were part of the establishment,” said Thiralal Bhusal, News Editor of The Kathmandu Post, an English-language daily under the KMG.

Even rival outlets expressed unease and concern. “It appears Kantipur was targeted due to perceptions about its coverage of the protests. There could also be the hand of party cadres who were not happy with its reporting. The media was largely critical in case of Rastriya Swatantra Party Chairman Rabi Lamichhane. The Maoists and pro-monarchy protesters were not happy, either,” observed Kosh Raj Koirala, Editor of Republica, another major English-language daily in Nepal.

Here was a disturbing twist: the press, often criticized for its biases and rivalries, suddenly found common ground in victimhood. The attacks were a reminder that when the structures of democracy wobble, the media’s vulnerability is laid bare for all to see.

However, it was not merely a Nepali affair. Should this be a struggle inside Kathmandu, its shock waves crossed borders. Indian reporters became lightning rods for anger too. Social networks erupted with clips of Indian reporters being mobbed, chased, and beaten. A Republic TV reporter was beaten up by demonstrators shouting, “Indian media go back.” His press card was torn away from him and thrown on the ground.

In another incident, South India Editor T. Raghavan of India TV and his cameraman Kiran Kumar were assaulted, their equipment nearly seized. These incidents revealed how a domestic revolt had spilled over into geopolitical sensitivities – where even neutral reportage was seen as intrusion or bias.

“They had not done anything wrong; they were merely reporting the agitations. But they became an object of anger and resentment and revealed how much a movement for domestic reform gets embroiled in geopolitical sensitivities,” a Nepali journalist reflected.

These attacks were not merely about people. They also symbolized an erosion of trust between the press and the publics, stoked by nationalist passion and chronic doubts. In a nation such as Nepal, where interactions with India are politically charged, Indian television crews became focal points for distrust. And distrust promptly spilled over into violence.

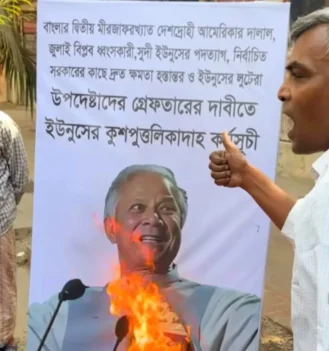

This is not an isolated pattern. When Bangladesh’s streets exploded in the summer of 2024, reporters found themselves standing not only on the frontlines of history, but in direct line of fire as well. In Dhaka, Sylhet, Sirajganj, and other urban centers, reporters who ventured out with notebooks and cameras fell casualty to the very violence they were reporting. The July “quota reform” protest alone claimed the lives of at least six reporters — including photojournalist Tahir Zaman Priyo, shot in the head while taking photographs at Science Laboratory intersection, and Abu Taher Md Turab of Naya Diganta, killed as he was caught in gunfire in Sylhet. Scores such as Dhaka Times’s Hasan Mehedi and Md Shakil Hossain of Gazipur fell to similar bullets as they attempted to do their jobs. Over two hundred others were wounded, pummeled with rubber bullets, caught in crossfires, or beaten up by ruling-party activists. Their cameras were smashed, their cars torched, their bodies battered.

But the assault was not only physical. As the protests deepened and Sheikh Hasina’s grip on power weakened, security agencies turned their focus to silencing the storytellers. Intelligence officers visited newsrooms and homes, demanding changes to coverage. Editors were threatened, reporters intimidated, and some were forced at gunpoint to reveal sources. Even established correspondents like Prothom Alo’s Asif Himadri were not spared — beaten by paramilitary forces outside Dhaka’s Secretariat while covering clashes.

The message was chillingly clear: in Bangladesh’s 2024 upheaval, bearing witness was itself treated as an act of defiance. Journalists became both chroniclers and casualties, their struggle mirroring the nation’s own fight for truth and accountability.

In Nepal and Bangladesh, protesters accused the press of complicity with the government, while the government blamed journalists for stoking protest. This double-front antagonism left correspondents vulnerable. The upshot is a “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” situation: too sympathetic and you are blamed for agitation, too critical and you are blamed for betrayal.

The Gen Z revolt revealed another sinister layer: infiltration. It became evident that certain forces with vested interests had exploited the unrest to attack the free press. The arson at major news outlets bore the marks of planning, not spontaneity. Meanwhile, the anti-Indian chants and assaults on foreign journalists deepened the historically delicate relationship between Nepal and India. Such interventions, whether deliberate or opportunistic, carried consequences far beyond the streets of Kathmandu, tarnishing Nepal’s image and alarming international observers.

“Incidents involving foreign journalists being threatened send a troubling message internationally. They raise concerns about press freedom in Nepal and may affect how the global community perceives the safety and openness of reporting during major public demonstrations,” observes Koirala.

Initially, despite the removal of the curfew orders, the journalists did not feel safe. Some wrote from secret locations, and some from makeshift office spaces at home. “We are all currently working from home as our offices and workstations have been burned down,” said Bhusal. For the reporters, the rebellion was as much a political event as it was a career meltdown.

That protest itself was not without fissures. There was argument over the choice of former Chief Justice Sushila Karki as an interim prime minister. There were preparations for fresh protest, and fresh danger for journalists. “If there are fresh protests in the days to come, protesters as well as the security personnel will need to exercise self-control and let the journalists work without interruption,” one Nepali journalist warned.

The reaction from the international community reinforced the gravity of the situation. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) criticized the attacks. Beh Lih Yi, CPJ’s Regional Director for the Asia-Pacific region, emphasized the need for accountability and protecting against retribution. These weren’t just attacks on individuals; they were attacks against the very fabric of democratic accountability.

And yet, despite all the censures, the structural weakness of the media was left bare. Polarization had penetrated even the newsroom. Media outlets wrote at length and with criticism, while others were criticized for walking party lines. Foreign networks, and specifically a few Indian ones, were censured for presenting the protests as monarchist instead of democratic—a mistake that stoked distrust. “This misrepresentation, in spite of a minority of Indian media, even raised further tensions and distrust,” observes one Nepali journalist.

This is the nub of the issue: media is not merely reporting conflict; it is becoming part of it. In fractured societies, every headline is questionable, every frame disputed. The Nepali rebellion brought starkly into focus just how precarious the balance is. To many protesters, the media was not the “fourth pillar of democracy” but an ally of the system they loathed. To governing elites, it was not a watchdog but an agitator. In between, the reporters themselves suffered the most—who was attacked by all and protected by none.

The story is eerily familiar. In Hong Kong’s 2019 protests, reporters were pepper-sprayed and beaten up despite clearly displaying press vests. In Myanmar after the 2021 coup, journalists became hunted prey, jailed for even using the word “coup.” Nepal’s events fit into this global trend where the media’s very attempt to document truth becomes an act of rebellion in the eyes of those in power—or those in the street.

The Gen Z rebellion in Nepal was about more than objecting to corruption or social media ban. It was a statement of generational outrage against a failed system. But the journalist attacks revealed something beneath the surface: an unsettling preparedness from actors—be they infiltrators, extremists, or spoilers—to strike against those who bare truths. The press was not an afterthought casualty; it was a conscious target.

The lesson is clear. A society without a free press is incapable of reforming itself. Burning newsrooms is not disabling the establishment; it disables people’s own voice. Attacking journalists is not buttressing a revolution; it is mis-shaping the revolution. Nepal is at a crossroads today. The Gen Z activists need to understand that suppressing the press is counterproductive to their own call for transparency. The state needs to grasp that attacking journalists is inconsistent with any democracy claim. And the international community needs to remain vigilant, lest Nepal drifts into a pattern where truth gets sacrificed first as the price of reform.

Finally, perhaps the Gen Z rebellion enlightened Nepal: in its young people, it saw energy; in its institutions, weakness; in its people, outrage against graft. But it also revealed the battlefield that is journalism itself. In Kathmandu and Dhaka, in Delhi and Hong Kong, the same script is played out: the liberty to report is as disputed as the liberty to protest. Unless that liberty is upheld, both democracy and dissent are perilously unfinished.