Bangladesh’s fragile democratic transition appears to be entering its most uncertain phase yet. As the national election approaches, the long-touted July National Charter for Consensus—once seen as a blueprint for rebuilding democratic trust—has become the very fault line dividing the nation’s politics. The carefully crafted narrative of unity that followed the 2024 student-led uprising, which toppled the Sheikh Hasina–led Awami League government, is now giving way to recriminations, disillusionment, and a crisis of legitimacy.

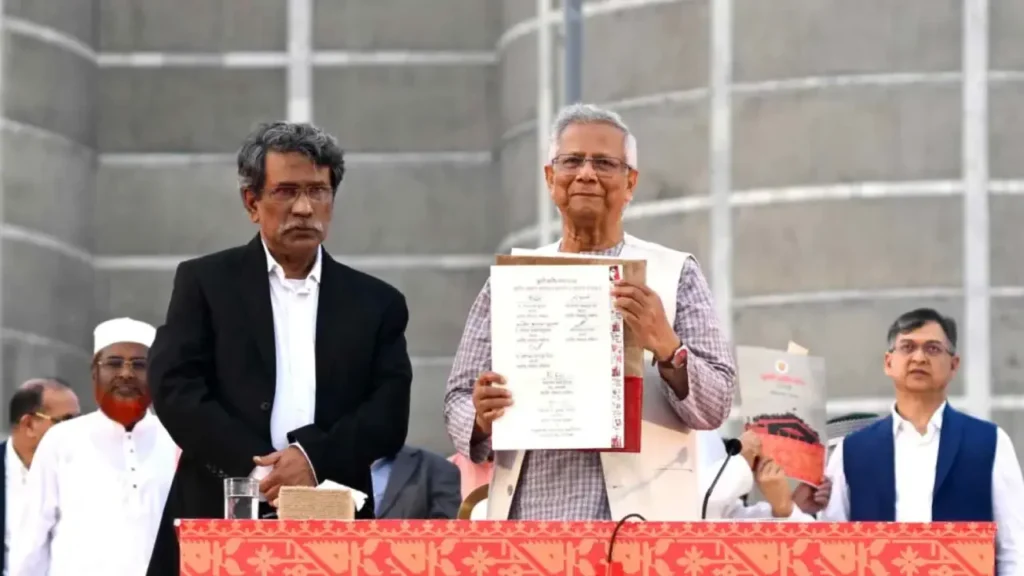

The latest political storm was triggered by two sharply contrasting but equally revealing statements. At the National Press Club in Dhaka, BNP Secretary General Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir launched one of his most severe attacks yet on the interim administration, accusing both the government led by Nobel Laureate Prof. Muhammad Yunus and the National Consensus Commission of betraying the faith of political parties and the people.

Citing the final report of the Commission, Fakhrul claimed that its recommendations deviated significantly from the agreements reached during earlier dialogues.

“The interim government and the Consensus Commission have betrayed the people’s trust. They have deceived the nation,” he said, accusing the Commission of omitting several dissenting notes officially submitted by opposition parties, including the BNP. He insisted that the party joined the Charter despite reservations, guided by the hope of consensus, but would pursue its reform agenda democratically through Parliament if elected to power.

“If the people vote us into power, we will implement our reforms through Parliament. If they do not, we will respect that verdict,” Fakhrul said, underscoring that the BNP’s faith in procedural democracy remained intact even as its trust in the transitional process eroded.

Fakhrul went further, questioning the legality of the proposed National Charter (Constitution Reform) Implementation Order 2025, reportedly under preparation by the interim government. Such an order, he argued, would carry the force of law under Article 152 of the Constitution and could only be issued by the President, not by an unelected authority.

Calling the move “a usurpation of power,” he warned that it would set a dangerous precedent for future administrations. He also dismissed calls from Jamaat-e-Islami and the National Citizen Party (NCP) for a pre-election referendum on the Charter, calling the idea “unnecessary and unwise.”

The only logical approach, he said, would be to hold the referendum alongside the parliamentary elections in February 2026—two ballots on the same day. In a veiled criticism of certain political factions, he added that those pushing for an early referendum were “misleading the public,” reminding that “the same groups opposed Bangladesh’s Liberation War in 1971.”

A consensus unravelling

In a rare moment of candour from within the government, Prof. Asif Nazrul, the Chief Adviser’s Legal Adviser, acknowledged that the divisions surrounding the Charter had reached a breaking point.

“The July Charter has been discussed for over 270 days. Yet instead of narrowing differences, divisions have only deepened,” he said at a press briefing at the Foreign Service Academy. Nazrul revealed that the Commission had presented two competing implementation models—one proposing a Charter Implementation Order followed by a referendum, with automatic enactment if Parliament failed to act within 270 days; and another recommending that the entire process be delegated to the next elected Parliament for formal adoption.

The political impasse, he explained, stemmed not just from disagreements over the Charter’s content, but also over its sequencing and legitimacy. “Political parties are now bitterly divided over both the process and the timing of the referendum. Even those who supported the July Uprising are now at odds with each other,” he observed, warning that if consensus continues to unravel, the legitimacy of the interim arrangement itself could be questioned.

“This government was conceived as a product of broad consensus among the July uprising forces. If that consensus collapses, the legitimacy of the entire arrangement comes into question,” he opined.

Political observers see these exchanges as symptomatic of a deeper malaise.

Fakhrul’s fiery rhetoric and Nazrul’s measured reflection together expose the widening fault lines between idealism and governance, between the vision of reform and the reality of politics. What was once celebrated as a people’s transition is now increasingly seen as a contested negotiation over who controls the narrative of change.

The BNP accuses the interim administration of procedural overreach and selective inclusion, while youth-led and pro-government groups like the NCP charge opposition parties with stalling reform.

Meanwhile, Jamaat-e-Islami has adopted a maximalist stance, demanding the full and immediate implementation of the Commission’s recommendations. Caught between these divergent pressures, the Chief Adviser’s Office has yet to decide whether the referendum will precede or coincide with the election, leaving the process suspended in uncertainty.

The road to 2026

As the Election Commission prepares to announce the electoral schedule within weeks, the interim government faces a narrowing window to restore consensus. Proceeding with an unresolved Charter risks undermining both the reform process and the credibility of the coming vote.

Political analysts argue that the struggle is no longer ideological but procedural—the battle is over who gets to define the terms of transition. As one Dhaka-based political scientist observed, “Bangladesh’s transition now hinges not on ideology, but on procedure. Whether the next government is born from consensus or confrontation will define the country’s democratic future.”

For now, the promise of unity that briefly animated Bangladesh’s post-uprising politics hangs in fragile balance. The Charter that once symbolised hope for a new beginning is now the center of a dispute that could determine not just the legitimacy of the next election, but the trajectory of the nation’s democracy itself.