Nearly fifty years after the dissolution of the notorious Rakkhi Bahini, Bangladesh’s interim government led by Nobel Laureate Professor Muhammad Yunus has launched a youth training initiative that has stirred unease across political, civil, and media circles. The programme, aimed at creating what officials describe as a disciplined and community-oriented “national defence preparedness force,” has revived haunting memories of a paramilitary past many thought was long buried.

The government insists that the new training scheme is designed to build discipline, civic responsibility, and readiness for national emergencies. But its resemblance to the early structure of the Rakkhi Bahini—a force infamous for political repression, extrajudicial killings, and human rights violations in the early 1970s—has prompted a wave of concern that Bangladesh might once again be walking a fine line between patriotism and paramilitarism.

A programme wrapped in patriotism

According to official statements, the interim government plans to train nearly 8,850 young men and women—of whom about 600 are women—in martial arts, self-defence techniques, and basic firearms handling at seven residential centres across the country. The Ministry of Youth and Sports is supervising the project through the Bangladesh Krira Shikkha Protisthan (BKSP). Officials claim the initiative aims to “foster national discipline and patriotism, preparing young people to respond during crises.”

Youth and Sports Adviser Asif Mahmud Shojib Bhuiyan has described it as a “mass defence strategy,” asserting that the trained youth could contribute during times of national crisis “if necessary.” He maintains that the programme will “instil resilience, discipline, and civic responsibility.” However, despite these assurances, no public legal framework, policy guidelines, or oversight mechanisms have been shared to legitimise or regulate the initiative. This lack of transparency has led many to question whether the programme even falls within the jurisdiction of the Sports Ministry.

The shadow of the Rakkhi Bahini

The unease surrounding the initiative stems from Bangladesh’s enduring memory of the Jatiyo Rakkhi Bahini (National Security Force), which was created in 1972 by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to maintain order in a war-torn nation. Initially formed with good intentions, the force soon became infamous for its alleged political repression, disappearances, and extrajudicial killings. After the 1975 coup that ended with Mujibur Rahman’s assassination, the Rakkhi Bahini was swiftly dissolved, its name forever etched into the national consciousness as a symbol of state excess and abuse of power.

Half a century later, the return of a similar model—even under a different guise—has revived deep anxieties. Critics argue that under the pretext of “youth empowerment,” the government might inadvertently create a force that could be used for political leverage or coercion.

Political and public reactions

The initiative has provoked mixed reactions. Political parties and rights organisations have condemned it, warning of potential misuse. A senior BNP leader, speaking to an English daily, remarked that the interim government should focus on holding free and fair elections rather than creating “a new force that could be politicised and interfere with the upcoming polls.”

Civil society voices have echoed these concerns. A lecturer at Dhaka University, requesting anonymity, said, “Bangladesh needs civic empowerment, not militarised youth reminiscent of 50 years ago.”

Meanwhile, government supporters see the initiative through a different lens, arguing that it is an effort to strengthen national unity and resilience after years of political turmoil. They insist that this is a temporary preparedness initiative, not a paramilitary structure.

Experts warn of accountability gaps

Security specialists and military experts, however, remain sceptical. Retired Brigadier General S. Rahman cautioned, “Bangladesh has a painful pattern. Mobilising such uniformed youth without safeguards or a clear command structure can erode professional law enforcement and public trust.”

Maj. Gen. (retd) ANM Muniruzzaman of the Bangladesh Institute of Peace and Security Studies echoed this sentiment, saying, “This is a completely wrong idea. Strengthening national defence capabilities requires a national policy approved through parliament—not an ad-hoc project run by the Sports Ministry.”

Criminologists have also warned that even basic weapons training could heighten instability if politically misused. “Trained youths can easily be manipulated by political or ideological forces,” said a Dhaka University professor. “Once trained, they can become unpredictable, and such skills can be turned against the very state that imparted them.”

Bangladesh already grapples with issues of small arms proliferation, political violence, and radicalisation. Experts caution that a loosely supervised youth training programme could deepen rather than solve these long-standing challenges.

Regional implications across the border

Given Bangladesh’s long and porous border with India, the move has attracted attention beyond Dhaka. Security analysts in New Delhi are closely observing the developments, warning that the training of civilians in basic weapon handling could raise regional security sensitivities—particularly if the programme extends into frontier districts.

India’s experience with cross-border militancy during the 1990s has made it wary of any form of civilian militarisation in neighbouring territories. While Dhaka maintains that the initiative is purely defensive, Indian analysts caution that it may be perceived as a sign of “paramilitary drift” — the slow blending of civilian and military structures.

Key governance questions remain unanswered. Under what legal authority is the training being conducted? Will the participants be vetted, monitored, or held accountable under existing defence laws? What happens once the training ends — do these youths report to any institution or remain unmonitored? How will weapons handling be regulated, and is live ammunition involved? Most importantly, who will ensure civilian oversight and transparency?

Without clear answers, the youth training initiative risks being seen less as a patriotic empowerment effort and more as a revival of paramilitary experiments from Bangladesh’s past.

Lessons from history

In post-war Bangladesh, the Rakkhi Bahini was formed to restore order and stability, but it soon became a tool for political control rather than national defence. Its dissolution following Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s assassination on August 15, 1975, left behind an enduring lesson: state power exercised through loyalist forces rather than accountable institutions inevitably breeds abuse.

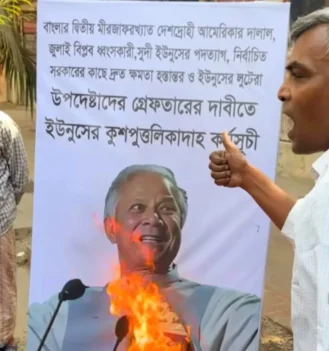

Today, the interim government, still grappling with legitimacy after Sheikh Hasina’s ouster during the 2024 student uprising, faces mounting pressure to maintain security and political stability. Yet turning to militarised youth mobilisation, critics say, may repeat history instead of rising above it.

A crossroads for Bangladesh’s democracy

There is no denying that Bangladesh, vulnerable to natural disasters and internal unrest, could benefit from a disciplined civic-defence or disaster-response force. The stated goals of discipline, patriotism, and national preparedness are laudable. But the line between a civic-defence programme and a politicised militia is a thin one — and that line is drawn by accountability.

Without parliamentary oversight, independent auditing, and clear demobilisation pathways, well-intentioned programmes can quickly transform into coercive instruments. “The difference between a civic-defence force and a militia lies not in its training but in its transparency,” noted one analyst.

For now, the Yunus administration insists that the programme is non-militarised and temporary. Yet, as more camps open and concerns deepen, Bangladesh stands once again at a pivotal moment in its democratic journey — between the promise of empowerment and the peril of militarisation.

Implications for Bangladesh-India relations

Though officially an internal initiative, the programme’s implications for regional security—particularly for India—cannot be dismissed. The two nations share extensive border cooperation between the Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) and the Border Security Force (BSF). Any increase in arms training for civilians, however limited, could alter that equilibrium and invite fresh scrutiny.

Indian strategists will likely interpret the rise of large-scale youth firearms training as a potential sign of militarisation in civilian spaces, especially against the backdrop of regional extremism and insurgent movements. While Dhaka asserts that its purpose is defensive and developmental, perceptions matter deeply in South Asia’s delicate security architecture.

What the programme claims to achieve

In its first phase, the training targets young citizens aged 18 to 35, who will undergo fifteen days of residential instruction at one of seven BKSP centres located in Dhaka, Chattogram, Khulna, Barishal, Sylhet, Dinajpur, and Cox’s Bazar. The training modules cover judo, karate, taekwondo, and firearms handling, though details about live firing remain unclear. Participants will receive full accommodation and a stipend of approximately Tk 4,200 during the training period.

The three-year pilot phase carries an estimated budget of Tk 28 crore. Official narratives describe the effort as one aimed at physical fitness, patriotic readiness, and national resilience. Adviser Asif Mahmud Bhuiyan explained in multiple interviews, “Given our military and geographical realities, mass defence is our only option. If someone has basic training and knows how to operate a weapon, they can serve the country if needed.”

However, defence analysts highlight that Bangladesh lacks a comprehensive national policy for citizen-based defence training beyond its formal armed forces and paramilitary units such as the Bangladesh Ansar and Village Defence Party. As Maj. Gen. (retd) Muniruzzaman observed, “If the goal is to strengthen national defence, there must be a clear framework approved at the national level — ideally through Parliament. This is not a matter to be handled lightly.”