Bangladesh finds itself at one of the most precarious junctures in its political history. A promised referendum that could reshape the nation’s governance framework and a war-crimes-style tribunal preparing to pronounce judgment on former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina have together set the stage for turbulence not seen since independence.

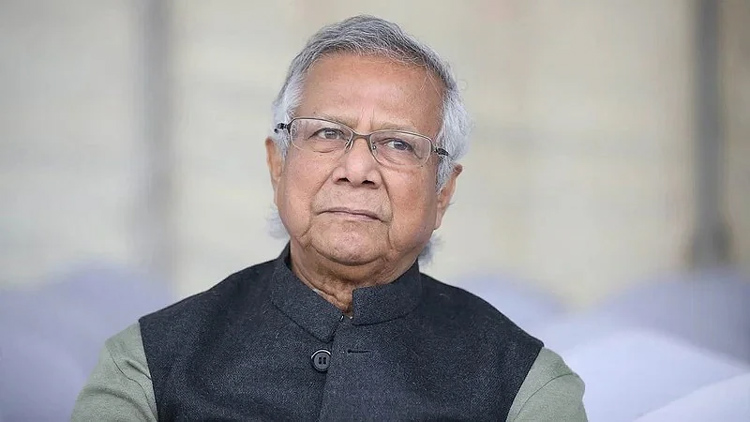

In a televised address on Thursday, Chief Adviser Dr. Muhammad Yunus announced that a national referendum on the landmark July National Charter for Reform would be held alongside the next parliamentary elections in February 2026. The Charter, drafted by the National Consensus Commission earlier this year, proposes sweeping constitutional changes — from reinstating a non-partisan caretaker administration and creating a bicameral legislature to curbing prime ministerial powers and strengthening judicial independence.

Yunus described the referendum as a democratic reaffirmation of the people’s will, asserting that the reforms were the outcome of national dialogue rather than partisan decree. The Charter stipulates that if Parliament fails to enact the proposed reforms within 180 days of its first sitting, the provisions will automatically be embedded in the Constitution.

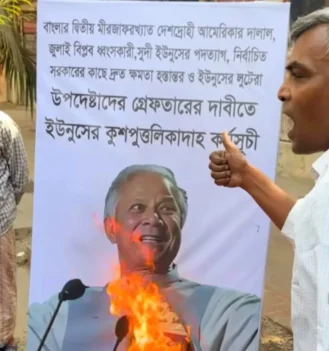

While Yunus defended the decision to hold the referendum alongside the national polls as cost-efficient and inclusive, critics have called it hasty and unilateral. The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), long a major political force, accused the interim government of imposing reform without political consultation. Acting chairman Tarique Rahman, speaking from London, warned that the move “disguises authoritarian control under the banner of reform.” Islamist parties such as Jamaat-e-Islami have also rejected the Charter, denouncing its secular clauses as “anti-faith” and “foreign-inspired.”

In contrast, centrist reformist coalitions and civic bodies have cautiously welcomed the decision, describing the referendum as an opportunity to restore public confidence in governance — provided the process remains credible. As one constitutional scholar in Dhaka noted, “Its legitimacy will depend entirely on fairness, not fatigue.”

The twin announcements have ignited tension across the country. Dhaka has witnessed a wave of arson attacks and explosions since Sunday, from the university precincts to its outskirts. Security forces have deployed 14 platoons of the Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) and heightened patrols in Gazipur and Narayanganj. The human rights body Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK) condemned reports of “shoot-on-sight” orders in Chattogram, warning that such measures risk escalating the crisis. University campuses — long mirrors of Bangladesh’s political mood — have again turned volatile, with students at Dhaka University marching under the slogan “Peace and reform, not repression.”

The unrest has spilled into diplomacy as well. Dhaka summoned India’s Deputy High Commissioner Pawan Badhe to protest recent interviews given to Indian media by Sheikh Hasina, now exiled in India and facing trial in absentia. The government accused New Delhi of providing a platform to a fugitive to incite disorder, warning that it undermines the spirit of mutual respect between the two neighbours. Analysts in Dhaka suggest the episode highlights Yunus’s difficult geopolitical balancing act: seeking legitimacy at home while maintaining trust with powerful regional partners.

Even as the political debate deepens, national attention is shifting to the International Crimes Tribunal-1 (ICT-1), which is scheduled to deliver its verdict on November 17 against Sheikh Hasina, former Home Minister Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal, and former police chief Chowdhury Abdullah Al-Mamun, who has turned approver. Presided over by Justice Md. Golam Mortuza Mozumder, the tribunal is trying the three for alleged crimes against humanity during the July 2024 student uprising that led to Hasina’s fall from power after 16 years in office.

The prosecution has charged them with five counts, including murder, extermination, torture, and other inhumane acts. The indictment cites several incidents, including the killing of student Abu Sayed in Rangpur, the shooting of six demonstrators in Dhaka’s Chankharpul area, and the burning of students in Ashulia — described by prosecutors as a deliberate act of extermination. Security across Dhaka has been tightened ahead of the verdict, with army patrols and 24-hour alerts in place.

The tribunal represents, for many, a moment of reckoning — both with an individual and an era. Supporters of the interim government view it as overdue justice for state violence; the Awami League, now operating in exile, condemns it as a political witch-hunt under judicial disguise. Human rights groups have urged transparency, warning that the perception of vengeance could delegitimize the process.

For Dr. Yunus, the stakes could not be higher. The Nobel laureate who entered office promising moral renewal and democratic reform now faces the toughest test of his credibility. His administration’s vision of institutional restructuring and civic participation risks being overshadowed by mounting unrest and polarizing narratives. As one Dhaka journalist observed, “Yunus is a reformer trapped by the caution that defines his legitimacy. He must show that reform can coexist with stability — or risk losing both.”

Bangladesh now awaits two decisive moments — the tribunal’s verdict on November 17 and the referendum alongside the February 2026 election. One looks back in judgment; the other looks forward in hope. Whether these processes reinforce democracy or deepen division will determine the nation’s immediate future.

For now, Dhaka’s streets remain restless, its campuses alive with protest, and its institutions weighed down by anxiety. As Yunus concluded in his address, “The people must decide whether we march forward together — or remain trapped in the past.” The coming months will reveal whether Bangladesh can compose a new chapter in its democratic journey — or whether, once again, the music will stop before the song is finished.