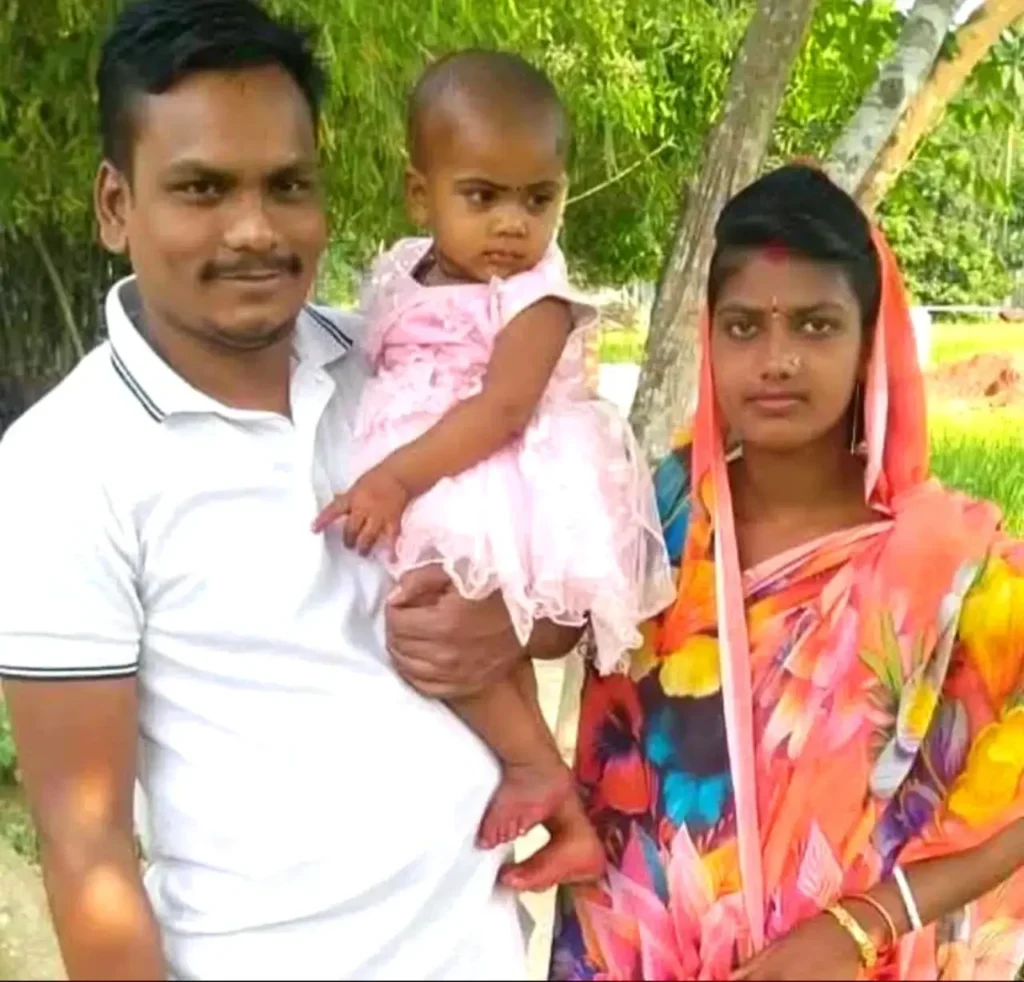

Dipu Chandra Das, a 27-year-old Hindu garment worker, ran for his life on the night of 19 December in Bhaluka, northern Bangladesh, fleeing a mob that had turned against him at his workplace.

Seeking protection, he reached the local police station, hoping the authorities would shield him from the violence.

That hope was shattered.

Hours later, he was dragged into the town square, tied to a pole, beaten, and set on fire as the tragedy unfolded before the community.

His death has sent shockwaves through the area and intensified fears among religious minorities, raising urgent questions over the capacity of the authorities to safeguard those most vulnerable.

Das was lynched and burned alive in Bhaluka, Mymensingh district, after allegations spread that he had insulted Islam — a claim police say has not been substantiated.

Videos seen by journalists show him inside a police station shortly before his killing, pleading for protection. What happened next remains unexplained.

Earlier that evening, Das was at work at Phoenix Knitting Ltd, where he had been employed as a garment worker.

Witnesses say rumours began circulating inside the factory that he had made offensive remarks about Islam. Within minutes, the atmosphere turned hostile.

Video footage shows Das surrounded by co-workers in a large room, blows raining down as he tries to shield himself.

“He was being beaten badly,” said one worker who witnessed the scene. “He somehow managed to escape. He ran straight to the police.”

Das fled to the nearby Bhaluka police station, believing it to be the one place the mob could not reach him.

In videos that later spread across social media, Das is seen inside the room of the station’s officer-in-charge, visibly shaken, gesturing anxiously as he speaks.

Outside the room, voices grow louder. A crowd gathers. They demand that he be handed over.

Witnesses say Das was taken to Bhaluka’s public square, tied to a pole or tree, beaten again and hanged. Several people told he showed signs of life when fuel was poured over his body and he was set on fire.

“The crowd stayed,” said a shopkeeper nearby. “Some people were filming. Some were shouting. No one stopped it.”

Videos circulating online show flames lighting up the night as onlookers stand nearby. Rights groups say the footage reflects not only brutality, but a sense of impunity.

On 20 December, Bangladesh’s elite Rapid Action Battalion (RAB-14) took over the investigation.

At a press briefing, officials said Das had been handed over to the mob by factory management while still on the factory premises.

Seven people, including the factory owner, have been arrested.

But that account has been questioned by journalists and rights groups, who point to video evidence showing Das inside the police station shortly before the killing.

“If he was inside the station, the authorities must explain how he was taken out,” said a lawyer from Supreme Court. “Either he was forcibly removed or he was handed over. Both raise serious concerns.”

Das’s father, Robilal Das, said he did not hear about his son’s death from the police.

“We started hearing things on Facebook,” he said. “Then people said he was beaten badly. After that, my brother came and said they tied my son to a tree.”

His voice faltered as he described what followed.

“They poured kerosene on him and set him on fire,” he said. “His body was left outside.”

The family says no government official has contacted them directly.

The killing has deepened fear among Bangladesh’s Hindu community, which makes up about 8% of the population.

A Hindu religious leader, speaking on condition of anonymity, said allegations of blasphemy — often fueled by rumours — have repeatedly sparked mob violence carried out by radicalized individuals, particularly under the Yunus regime.

Under the same government, Islamist hardliners have gained space to operate with impunity, radicalisation is intensifying, and religious minorities increasingly face threat.

“The state’s failure to intervene, even as a man sought protection from the authorities, has left a profound void — a silence that reflects the erosion of trust in institutions meant to safeguard life and justice,” he added.

Source : The Chittagong Hill Tracts