Myanmar is scheduled to go to the polls on December 28, marking the first election since the military coup of February 1, 2021. Far from signalling a democratic restoration, the vote is being conducted under tightly controlled conditions with the armed forces exercising total authority over the process—an exercise many critics have described as a “military-controlled ballot.”

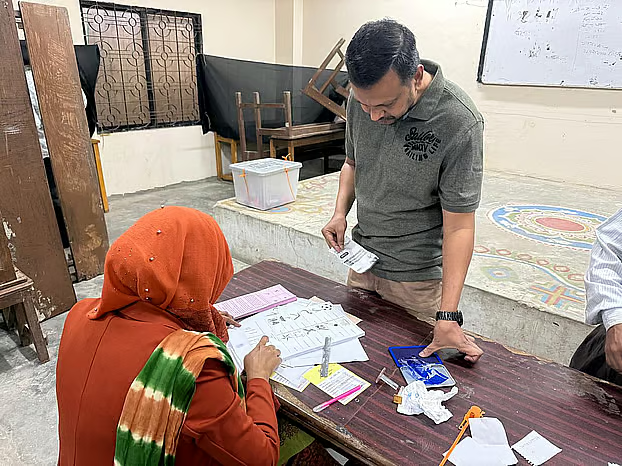

The junta’s Union Election Commission (UEC) has announced that elections will be held in 274 of Myanmar’s 330 townships, spread across three phases on December 28, January 11, and January 25, 2026. Whether the polls will attract any meaningful turnout remains uncertain. The run-up to the elections has been marred by escalating violence, intimidation, and arbitrary arrests, leaving little room for free expression, political mobilisation, or genuine participation.

Most major political parties have been eliminated from the process. Chief among them is the National League for Democracy (NLD), which won landslide victories in the 2015 and 2020 elections. The party was dissolved by the UEC after refusing—or being unable—to re-register under restrictive new legal requirements. In effect, the electoral field has been cleared of all parties that previously commanded popular support.

Although the military has framed the polls as a return to multi-party democracy, critics see the exercise as an attempt to manufacture legitimacy. Opposition to the elections has been strong, both domestically and internationally. Naw Susanna Hla Hla Soe, an NLD member of parliament re-elected in 2020 and later ousted during the coup, told DVB News that it was essential for the international community to understand the reality on the ground. “This election is not free and fair,” she said.

Hla Hla Soe, who served as the National Unity Government’s Minister of Women, Youth and Children’s Affairs from 2021 to 2025, warned that the process was merely an effort by the military to claim legitimacy, urging the international community not to “fall into the trap” and instead stand with the people and listen to their voices.

The 60-day electoral campaign officially ended on December 26 amid heightened security. Candidates, voters, and poll workers have all expressed fears of election-related violence. Since the enactment of the Election Protection Law on July 29, at least 267 people have been charged under its provisions, 49 arrested, and nine convicted.

Observers quoted by local media have criticised the coercive atmosphere, stressing that voting must remain a matter of personal choice and that no authority should force citizens to participate in, or endorse, an electoral system they do not believe in.

Veteran international election observers who monitored Myanmar’s 2015 and 2020 polls have been blunt in their assessment. Many argue that it is meaningless to speak of free or credible elections when the same military that seized power in 2021 is now administering the vote. As one senior observer with extensive experience in Myanmar put it, there is no “level playing field” in a process that is fundamentally one-sided.

The United Nations has echoed these concerns. UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk has warned that the elections will take place in an environment of violence and repression, calling their legitimacy into question. According to Türk, there are no conditions in Myanmar for the meaningful exercise of freedoms of expression, association, or peaceful assembly.

Domestic analysts and international experts alike point out that the exclusion of all major parties that performed well in previous elections speaks volumes about the intent behind the process. In this context, the military appears to be paving the way for a quasi-civilian administration dominated by its own political vehicle, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP). Such an outcome would allow the junta to claim that elections demonstrate progress toward inclusiveness, aligning rhetorically with ASEAN’s five-point consensus, which calls for constructive dialogue among all parties to seek a peaceful solution in the interests of the people.

The first phase of voting, scheduled for December 28, is taking place more than four years after the military seized power, dissolved major parties, and jailed thousands of opponents. Key political figures, including State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint, remain imprisoned.

Since the coup, Myanmar has descended into widespread armed conflict, mass displacement, and economic collapse—crises further aggravated by devastating earthquakes in March 2025 that deepened humanitarian suffering across large parts of the country.

Despite deteriorating battlefield conditions in multiple regions, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing and the State Administration Council (SAC) have consistently projected an image of stability. Their narrative portrays the conflict not as a crisis of legitimacy but as a response to “terrorist threats” requiring firm control.

By repeatedly invoking the 2008 Constitution—which entrenches sweeping military privileges—Min Aung Hlaing presents himself as steering Myanmar toward a form of controlled federalism. This messaging is carefully calibrated: it reassures the military’s domestic support base while signalling to external actors the promise of a gradual, managed transition.

Central to this strategy is the 2023 Political Parties Registration Law, which fundamentally reshaped Myanmar’s political landscape. The law imposes onerous conditions on parties, including large membership thresholds and requirements to contest elections across multiple regions—criteria impossible for opposition groups operating in exile, underground, or under constant repression.

Through this legal framework, the NLD was deregistered, dozens of smaller parties were dissolved, and the political field was effectively reserved for the USDP and other military-aligned entities. The law forms the scaffolding of a carefully constructed façade of pluralism designed to preserve absolute military control.

As resistance and public apathy toward the elections grew, the junta introduced legislation criminalising “election interference.” In practice, this has served as another tool to suppress dissent. Thus far, at least 229 people have been detained on accusations of disrupting the election—often for nothing more than criticising the process verbally or on social media.

The human cost of repression has been severe. Aung San Suu Kyi and Win Myint have been in detention since the day of the coup. The NLD reports that since 2021, 102 of its members, including two MPs elected in 2020, have been killed, while 1,905 members—among them 144 elected parliamentarians—have been arrested. Many NLD members who avoided arrest or death have joined the National Unity Government (NUG). Both the NLD and the NUG have categorically rejected the 2025–26 elections.

Public resistance continues across the country. Protests against what many describe as a sham election have been reported in multiple regions, including Yinmapin Township in Sagaing Region, where demonstrators marched with banners declaring, “Don’t legalize murder with your vote.”

The election is widely dismissed as a hollow exercise, given the ongoing civil war, the absence of real competition, and the systematic disenfranchisement of popular political forces. Yet for the junta, the process is strategically indispensable. The Political Parties Registration Law ensures that only compliant or military-approved parties can participate, turning the election into an instrument of political engineering rather than democratic choice.

International perception remains critical to this strategy. Western governments have rejected the legitimacy of the polls, but the regional response is fragmented. ASEAN has declined to send an official observer mission while leaving room for bilateral engagement.

Thailand has criticised the detention of political prisoners but suggested that even an imperfect election could contribute to stability. Russia and Belarus have openly endorsed the process and will send observers, while China has expressed support for elections in principle and engaged in discussions on voting technology.

These varied responses—some tacit, others explicit—provide the junta with enough external validation to argue that its electoral roadmap is internationally engaged, even if deeply contested. Domestically, the military is also seeking to capitalise on war fatigue. By offering a return to politics, however stage-managed, it presents itself as the only actor capable of administering a nationwide process.

Whether citizens truly believe this narrative is secondary; what matters for the junta is fostering the perception that no viable alternatives exist.

Even so, the credibility of the election remains deeply compromised. Resistance groups have vowed to disrupt the vote, and the UN has warned that it will be conducted in an environment “rife with threats and violence,” with political participation actively suppressed.

The military’s insistence on proceeding regardless underscores how central this election is to its long-term strategy—not as a democratic exercise, but as a calculated bid to consolidate power under the guise of civilian rule.