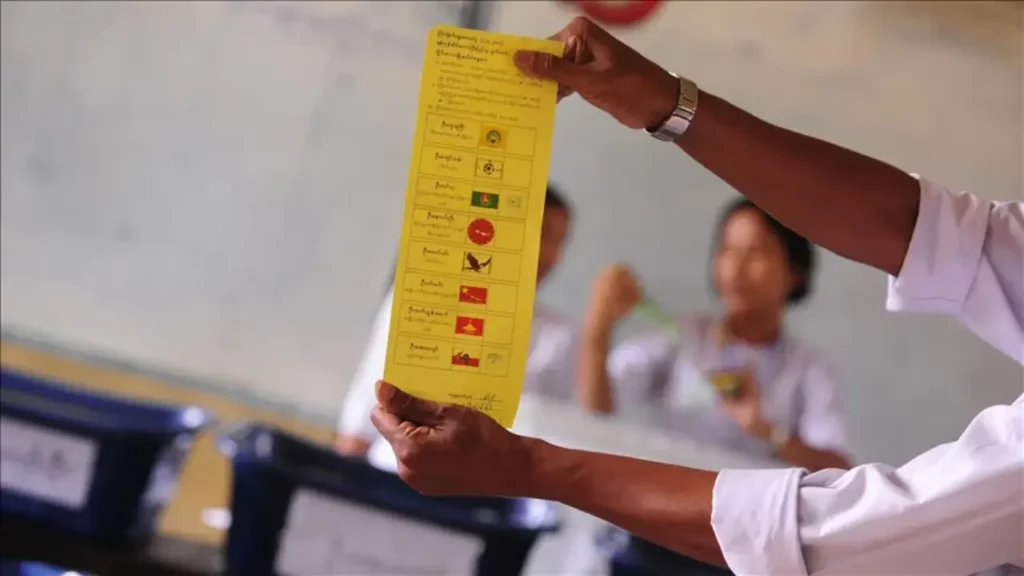

The upcoming elections in Myanmar—the first since the 2021 military coup d’état—are scheduled for 28 December 2025 and are being held in an atmosphere marked by fear, violence, and deep political, social, and cultural repression. Thousands have been detained since the coup, and several political parties believed to be inherently opposed to the interests of the Myanmar Armed Forces (MAFs) have been excluded from the ballot, signalling that democracy remains a distant dream. Although the military rulers had earlier promised to hold elections by August 2023, these were repeatedly delayed due to escalating violence.

Given this legacy and the current situation, Rakhine State continues to draw the attention of strategic thinkers and policymakers. Any proposed election naturally raises two critical questions: whether elections will actually take place in Rakhine State, and what the future of the state will look like thereafter.

In Rakhine State, the Arakan Army/United League of Arakan (AA/ULA) currently dominates the ground situation, with 14 of the state’s 17 townships under its control. Since its inception on 10 April 2009 in Laiza, Kachin State, and its relocation to Rakhine State in 2014, the AA has maintained close associations with other Ethnic Armed Groups (EAGs), including the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and the Three Brotherhood Alliance, comprising the Arakan Army (AA), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA).

The AA has experienced both setbacks and surges. In 2020, it was designated a terrorist organisation by the then Aung San Suu Kyi–led government instead of being recognised as an EAG, and this designation was again applied in December 2023 by the MAFs. However, in many instances, the AA has suffered more in nomenclature than in operational capability.

The first question: The elections

As a prelude, it is important to recall the 2020 elections, during which polling was cancelled by the Union Election Commission (UEC) in nine northern townships of Rakhine State due to the threat of armed violence. Days before the November 2020 elections, the MAFs and the AA had agreed to a peace deal. After the 2021 coup, the AA did not break that truce, and the State Administration Council (SAC) subsequently lifted the “terrorist” designation imposed on the AA.

Voting in 2020 was permitted in the state capital, Sittwe, and in other townships of southern Rakhine State. Only about 25 percent of the state’s 1.6 million eligible voters were allowed to cast their ballots. The Arakan National Party (ANP) defeated the ruling National League for Democracy (NLD) in Rakhine State, securing a majority of the constituencies, while the Arakan Front Party (AFP) won two state parliamentary seats in Kyaukphyu.

Today, amid renewed clashes between the MAFs and the AA, the political environment is “rife with threats and violence,” with political participation actively suppressed. Over the past five years, Rakhine State has become practically autonomous—though with an as-yet undefined political objective of self-determination—while remaining, technically, a state within Myanmar.

At present, the AA has reportedly captured 14 of Rakhine State’s 17 townships, leaving the military government nominal control over Sittwe, Kyaukphyu, and Manaung. Amid significant military tensions, junta officials convened a meeting on 25 November to discuss election security in Sittwe. This exercise appeared largely symbolic.

The UEC’s list of no-election areas released on 14 September 2025 did not include AA-controlled Ann, Thandwe, Taungup, and Gwa among the 56 townships across eight states and regions where elections were ruled out. According to the MAFs and the UEC, elections may still be possible in seven townships: the AA-controlled Ann, Thandwe, Taungup, and Gwa, and the Tatmadaw-held Sittwe, Manaung, and Kyaukphyu.

In the first phase of elections scheduled for December, 102 townships are to vote, including Ann, Thandwe, Taungup, and Gwa—despite these areas remaining under AA control. Regional military commanders have not regained control over these townships, suggesting that elections will, in reality, be held only in the three townships firmly under MAF control. Elections are unlikely to take place in AA-controlled Ranbye, Pauktaw, Ponnagyun, Rathedaung, Buthidaung, Maungdaw, Kyauktaw, Minbya, Mrauk-U, and Paletwa.

In the limited number of townships where elections may occur, the contest is expected to involve the Arakan Front Party (AFP), the Arakan National Party (ANP), the Rakhine State National Force Party (RSNFP), the Khami National Development Party (KNDP), the Mro Ethnic Party, the Mro Ethnic Development Party, and MAFs-controlled parties. In contrast, the 2020 elections featured competition between AA/ULA-backed forces, Rakhine-based ethnic parties, and military-aligned parties.

MAFs-run newspapers reported on 6 December 2025 that around 71 wards and village tracts in Sittwe and Kyaukphyu under military control would not conduct elections, further underscoring the deteriorating security situation.

For the MAFs, holding elections is primarily about optics and symbolism. A successful exercise would reassure partners and constituencies of the military’s capacity to safeguard current and future projects, both within areas under its control and beyond. However, global institutions, including the UN Human Rights Office and the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), continue to prioritise ending violence and ensuring the flow of humanitarian aid.

Meanwhile, the pro-military Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) reportedly began election campaign activities in Rakhine State as early as December 2022. The AA, the real power broker in the state, has vowed to block elections in areas it controls, challenging the junta’s legitimacy rather than participating as candidates or voters. Having built parallel governance structures and popular support, the AA represents a major obstacle to the MAFs’ political ambitions.

An MAF airstrike on 10 December 2025 on Mrauk-U Hospital killed 34 people and injured at least 80 others. This attack effectively sealed the fate of any meaningful elections in Rakhine State and strengthened the AA’s resolve to oppose the MAFs and the upcoming polls with greater determination. Such airstrikes also reflect the MAFs’ confidence that the AA will not retaliate against the three townships under military control, owing to the MAFs’ superior military capabilities and the regional influence of China and India.

One key consequence of the absence of elections in Rakhine State is the likelihood that increasing numbers of Rakhines will gravitate toward armed rebellion against the MAFs.

The second question: The future

It is evident that the AA will neither guarantee nor participate in the upcoming polls—sham or otherwise—in Rakhine State and parts of Chin State. Once elections are held, successfully or otherwise, in other parts of Myanmar, attention will shift to the humanitarian, security, and political future of AA-controlled areas.

The AA’s journey will not be without challenges. Ideological, religious, and political considerations will need to be carefully balanced, as these factors heavily influence global perceptions of the group. Since the February 2021 coup, the AA has administered large rural areas of Rakhine State, building popular support through its swift justice mechanisms and governance model. Its stated priority is to construct a post-election Rakhine State through expanded economic, agricultural, health, social, cultural, and security policies.

However, political clarity remains elusive. There has long been ambiguity regarding the AA’s ultimate objectives for itself and for Rakhine State, reflected in its shifting demands for autonomy, self-determination, or secession from Myanmar.

Rakhine State remains entangled in a complex web of ethnic conflict, military resistance, and prolonged persecution, making it a fragile and volatile region with acute humanitarian needs. As the Myanmar military loses ground elsewhere, Rakhine risks plunging into deeper isolation, ethnic tension, and humanitarian crisis, threatening regional stability.

Following Operation 1027, Rakhine State has been largely cut off from other regions of Myanmar and the outside world. The MAFs have blocked routes connecting the state to Myanmar’s central regions and have continued aerial bombardments, killing civilians. Border gates to India are closed due to disease outbreaks, while Bangladesh shut its borders in July 2025 amid clashes between Rohingya militant groups and the AA.

The region’s history of militarisation and violence suggests that its population has long struggled for survival and will likely continue to do so. Unresolved Rohingya repatriation issues and allegations of war crimes further complicate peace-building and governance efforts.

The ULA has acknowledged the complexity of the Rohingya issue and expressed interest in addressing the fate of nearly one million Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. However, whether Bangladesh is willing to engage directly with the AA, bypassing the MAFs, remains uncertain. Although Bangladesh’s interim government briefly explored the idea of a humanitarian corridor into Rakhine State, the proposal was withdrawn under domestic pressure.

The responsibility for the estimated 600,000 Rohingya still in Rakhine State—confined to camps and villages with restricted movement and limited access to food, healthcare, education, and livelihoods—rests largely with the AA. Deep-seated mistrust between Rakhine and Rohingya communities persists, exacerbated by administrative challenges and allegations of exploitation related to salary mobilisation for teachers in Rohingya areas.

On the security front, the AA remains aware of its asymmetry with the MAFs, which possess superior air and naval capabilities and are supplied by China, Russia, and Belarus. Control over key ports and trade corridors could, however, provide the AA with strategic leverage affecting both Chinese and Indian interests.

Future governance in Rakhine State may resemble the Wa State model, administered by the United Wa State Army (UWSA), which operates with its own political and economic systems while remaining nominally part of Myanmar. The AA has not been able to fully take over Rakhine State due to strong MAF deployments in Kyaukphyu and surrounding areas, coordinated land, air, and naval forces, and external influences.

The repelling of a February 20, 2025 MAF offensive, reportedly at significant cost to the AA, highlights these constraints. Continued MAF control over banking, electricity, and essential commodity flows further limits AA authority.

Over time, the Rakhine–Bamar administrative and security divide may become entrenched, potentially leading to a Wa State–like governance structure post-elections. Economic isolation imposed by the MAFs is likely to persist as long as the AA refrains from attempting to capture the remaining three townships under Tatmadaw control.

Amid shifting power dynamics across eight states and regions, Myanmar’s administrative map and governance systems are poised for significant change—changes for which many anti-military forces remain unprepared. The AA faces daunting challenges ahead, including the risk of escalating conflict, renewed Rohingya crises, and worsening humanitarian conditions driven by poverty, displacement, and weak rule of law.

Ultimately, the AA appears prepared for the first question—the elections—but much remains unresolved regarding the second: the future of Rakhine State. Time, along with regional and global responses, will shape the outcome.