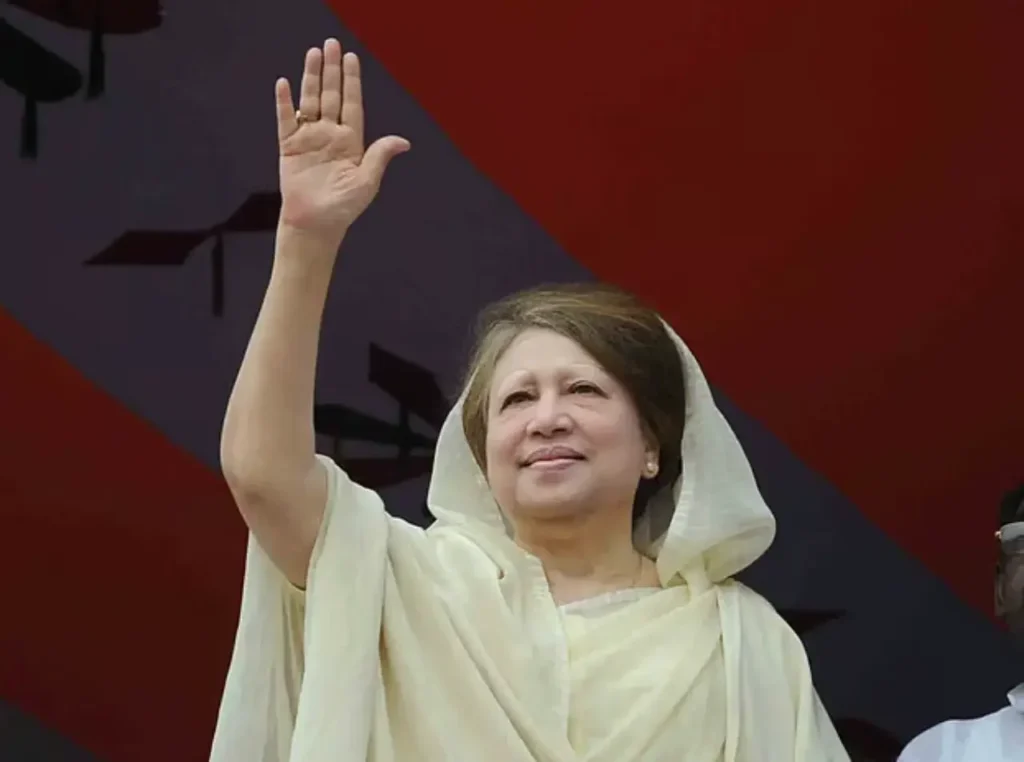

With the death of Begum Khaleda Zia at 79 on Tuesday, Bangladesh loses a former prime minister whose political life was closely intertwined with the country’s modern democratic experience. Her passing marks the end of a generation of leaders shaped by confrontation, mobilisation, and electoral competition at a time when politics—often adversarial and deeply polarised—was still anchored in the expectation of popular mandate.

Khaleda Zia operated within a political tradition where power was contested openly, sometimes acrimoniously, through elections, mass movements, and street politics. She was not alone in this tradition, but she remained one of its most enduring representatives. Across decades of political upheaval, she remained rooted in the language of popular legitimacy and competitive politics.

Her life reflected both the possibilities and limits of Bangladesh’s democratic journey. It was a career marked by resilience, contradiction, and survival—shaped as much by personal loss as by political struggle.

Early life before power

Khaleda Zia was born on August 15, 1946, in the final year of British India. Though her birth preceded Partition, her upbringing took place entirely in what later became Bangladesh. Her family background reflected provincial Bengal rather than political privilege, with roots in both the southeastern and northern districts of the region. The family eventually settled in Dinajpur, far from the centres of political power.

Her education unfolded in local missionary and government institutions, and her early years were marked by routine rather than public engagement. Those who knew her in this period described a quiet, reserved young woman, with little interest in politics or public life.

Her marriage in 1960 to Ziaur Rahman, then a young army officer, introduced her to the disciplined and transient life of military families. Frequent transfers, long separations, and the demands of cantonment life defined her adult years. She remained outside politics, focused on family and domestic responsibilities as her husband rose through the military ranks.

The Liberation War of 1971 marked a decisive rupture. While Ziaur Rahman joined the armed resistance, Khaleda Zia remained behind with her children and was detained by Pakistani forces until the war’s end. She rarely spoke publicly about this period, treating it as a personal hardship rather than a political credential. Even after independence, and later during her years as First Lady, she remained distant from politics until Ziaur Rahman’s assassination in 1981 drew her into public life.

From opposition to office

Khaleda Zia’s political emergence took place during the resistance to General Hussain Muhammad Ershad’s military rule in the 1980s. At a time when opposition politics faced severe constraints, she became a prominent figure in the movement demanding a return to democratic governance.

Her decision to boycott the 1986 elections under Ershad’s rule was controversial, including within opposition circles. Yet it reinforced her image as a leader unwilling to lend legitimacy to a political process she considered flawed. Over time, this stance strengthened her standing among supporters.

In 1991, following the restoration of parliamentary democracy, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party won national elections, and Khaleda Zia became Bangladesh’s first elected female prime minister. Her assumption of office through a widely accepted electoral process marked an important moment in the country’s democratic transition and reflected the continuing role of competitive politics in shaping leadership.

Governing Bangladesh

Khaleda Zia’s periods in office reflected both achievement and limitation. Parliamentary practices were revived, press freedoms expanded, and civilian authority was reaffirmed after years of military dominance. Her governments operated within a highly polarised political environment, yet electoral competition remained central to political legitimacy.

At the same time, governance challenges persisted. Political confrontation between major parties intensified, institutions faced strain, and reform efforts were uneven. These difficulties were not unique to her tenure but reflected broader structural and historical challenges within Bangladesh’s political system.

Her final full term from 2001 to 2006 coincided with rising concerns about governance, internal party dynamics, and the functioning of state institutions. While these years proved difficult, they also underscored the complexities of governing within a deeply divided political landscape.

Detention, resistance, and political standing

The military-backed caretaker government of 2007–08 marked another significant phase in Khaleda Zia’s life. Her arrest and detention during the “One-Eleven” period placed her once again at the centre of national political turbulence.

She declined to enter political arrangements that would have removed her from leadership, choosing instead to endure imprisonment and sustained legal pressure. This period reinforced her standing among supporters as a leader willing to bear personal cost rather than withdraw from political life.

In subsequent years, her political role became more constrained, shaped by legal proceedings, health concerns, and limited public engagement. Over time, she came to represent continuity and endurance rather than active leadership, retaining symbolic importance within opposition politics.

Later years under Sheikh Hasina’s government

During Sheikh Hasina’s tenure, Khaleda Zia’s political life was marked by prolonged legal battles, periods of incarceration, and declining health. Multiple cases kept her away from active politics, while age-related illnesses and serious medical conditions worsened over time.

This period also unfolded against the backdrop of one of South Asia’s most enduring political rivalries. The adversarial relationship between Khaleda Zia and Sheikh Hasina—rooted in personal tragedy, opposing political traditions, and decades of mutual distrust—had long shaped Bangladesh’s political culture. Their rivalry extended beyond electoral competition, influencing party structures, public discourse, and the tenor of governance itself. As a result, Khaleda Zia’s imprisonment and legal struggles were widely viewed not only through a judicial lens but also as part of this prolonged political contest between two dominant leaders.

Requests for advanced medical treatment, including treatment abroad, became a recurring issue and a point of public debate, drawing attention to humanitarian considerations alongside legal processes. These years raised broader questions about political rivalry, justice, and the treatment of opposition leaders.

Following her release under restricted conditions, Khaleda Zia largely withdrew from day-to-day political activity. Her presence remained important symbolically, serving as a reference point for opposition politics rather than as an active organiser or campaigner.

Four decades leading the BNP

For more than four decades, Khaleda Zia remained the central figure of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party. From assuming leadership in 1981 after Ziaur Rahman’s assassination to her final years away from active politics, she provided the party with continuity and cohesion.

Under her leadership, the BNP evolved into a major electoral force and the principal alternative to the Awami League. Even during periods of repression, organisational strain, and leadership exile, her authority within the party remained largely intact.

Her 42-year tenure as party chairperson shaped not only the BNP’s identity but also the broader structure of Bangladesh’s competitive, adversarial political system, making her leadership one of the longest and most influential in the country’s history.

Family, loss, and the final chapter

Khaleda Zia’s later life was marked by personal loss and prolonged separation from family. After the death of her younger son, Arafat Rahman, she lived for 17 years in Bangladesh without her elder son, Tarique Rahman, who remained in exile in London.

Only on December 25, after 17 years abroad, did Tarique Rahman return home with his family—shortly before Khaleda Zia’s death. The long separation reflected the personal toll of Bangladesh’s extended political conflicts.

Following the mass uprising of 2024 that brought an end to Sheikh Hasina’s rule, Khaleda Zia’s response was measured and restrained. She spoke of reconciliation and renewal rather than retribution, signalling a desire for political closure.

Khaleda Zia’s death leaves a significant absence in Bangladesh’s political life. She will be remembered not as a flawless leader, but as a consequential one—whose endurance, presence, and electoral legitimacy helped sustain competitive politics through decades of upheaval.