When Khokon Das closed his small medical shop in southern Bangladesh on the night of Dec. 31, he expected a familiar walk home.Instead, he was ambushed, stabbed, beaten and set on fire, according to police and witnesses — the latest in a string of violent attacks that have left the country’s Hindu minority fearful and increasingly uncertain of their safety.

Das, 50, survived only because he managed to leap into a nearby pond after assailants doused him with petrol and ignited the flames, residents said.

He was later transferred to Dhaka Medical College Hospital, where doctors said he was being treated for burn injuries and stab wounds.

“They stabbed him in the stomach, hit his head and then set him on fire,” his wife said from the hospital, her voice breaking.

“My husband is a simple man. He treats poor people. He never harmed anyone. We are begging for justice.”

The attack in Shariatpur district is the fourth reported assault on a Hindu individual in Bangladesh in less than two weeks, following a series of incidents that have included lynchings, arson and public burnings.

Together, the attacks have heightened concern among minority communities, who say they point to a climate of growing lawlessness and religious radicalisation during a fragile political transition.

On Dec. 24, a 29-year-old Hindu man, Amrit Mondal, was beaten to death by a mob in the Hossaindanga area of Kalimohar Union, according to police and local residents.

Authorities said the killing stemmed from a local dispute and rejected suggestions of a communal motive.

But residents described a scene of unchecked violence.

“The fanatics were shouting and hitting him openly,” said a villager who witnessed the attack and asked not to be named.

“No one stepped in. Everyone was afraid.”

Earlier, on Dec. 18, Dipu Chandra Das, a 25-year-old garment worker, was lynched in Bhaluka, in the Mymensingh district, after being accused of making derogatory remarks about Islam — an allegation his family denies.

According to local journalists and eyewitness , Das had gone to a police station seeking protection after threats escalated.

Instead, he was later forced to resign by factory supervisors, expelled from his workplace and handed over to a mob, which beat him to death.

His body was subsequently hung from a tree and set on fire.

A senior lawyer of the Bangladesh Supreme Court described the killing as emblematic of a broader breakdown.

“It reflects a climate of impunity,” the lawyer said.

“Religious extremism has been allowed to spread amid administrative inertia and the steady erosion of state authority.”

Bangladesh, a Muslim-majority nation of about 170 million people, has a long history of communal coexistence but also periodic outbreaks of violence against minorities, particularly Hindus, who make up roughly 8 percent of the population.

Such attacks have often coincided with moments of political instability.

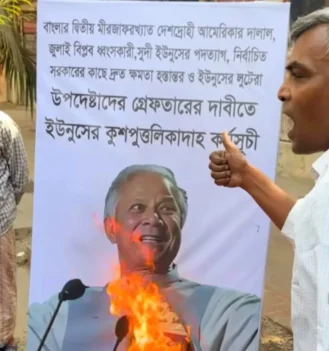

The recent incidents have unfolded under an interim government led by Muhammad Yunus, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate, who took office after the collapse of the previous administration.

Yunus has pledged to restore stability and uphold the rights of all citizens, regardless of faith.

Government officials have condemned individual acts of violence and said investigations are underway.

In the case of Mondal’s killing, authorities said the attack was linked to criminal activity rather than communal hatred.

“When victims repeatedly come from the same community, dismissing the pattern undermines trust,” said the lawyer.

“Violence becomes self-perpetuating when perpetrators believe they will face no consequences.”

In Shariatpur, the attack on Das has left residents shaken.

“People are afraid to walk home after dark now,” said a nearby shopkeeper. “We keep asking ourselves: if this can happen to him, who is next?”

The violence has also triggered political recriminations.

Sheikh Hasina, the former prime minister who was ousted earlier this year, accused the interim administration of failing to protect religious minorities and allowing radical elements to gain influence — allegations the government has not addressed in detail.

For many Hindus, the immediate concern is not political blame but survival.

“We hear statements after every incident,” said a community elder in southern Bangladesh. “But statements do not stop knives or fire.”

As Khokon Das remains hospitalised, his neighbours say the sense of vulnerability is growing — along with a fear that the attacks are no longer aberrations, but part of a dangerous pattern that threatens the state’s ability to protect its most vulnerable citizens.

“We used to worry during elections,” the elder said quietly. “Now we worry every night.”

Source : The Cittagong Hill Tracts