Samir Das was an ordinary Hindu auto-rickshaw driver with no political affiliation, no public voice, and no protection—yet he was beaten to death in Daganbhuiyan in Chittagong in mid-January. His killing was not the result of a riot, a clash, or an accident; it was a brutal act of targeted violence against a minority citizen going about his daily life. Instead of triggering national outrage or urgent state intervention, Samir Das’s death passed with disturbing quiet, signalling a deeper malaise in Bangladesh today: a steady escalation of communal violence that has failed to stir the conscience of the interim government led by Chief Adviser Professor Muhammad Yunus.

Samir Das’s murder was not an aberration. It was the latest entry in a grim tally—at least fifteen Hindu minorities killed in just forty-five days between 1 December 2025 and 15 January 2026, amounting to one killing every three days.

The victims of these dastardly killings include Samir Das and Prolay Chaki (11 January), Joy Mohapatra (10 January), Mithun Sarkar and Sarat Mani Chakraborty (6 January), Rana Pratap Bairagi (5 January), Khokon Chandra Das (31 December), Bajendra Biswas (29 December), Amrit Mondal (24 December), Dipu Chandra Das (18 December), Shanto Chandra Das (12 December), Jogesh Chandra Roy and Suborna Roy (7 December), and Prantosh Kormokar and Utpol Sarkar (2 December). These killings span districts and demographics, claiming elderly women like Suborna Roy and young men such as 18-year-old Shanto Chandra Das, underscoring the indiscriminate vulnerability of Hindu minorities across the country.

The nature of the violence reveals intent rather than spontaneity. Several murders were reportedly premeditated, with victims’ assets deliberately targeted—auto-rickshaws seized, livelihoods destroyed, families terrorised. Some killings were carried out with chilling brutality, including throat-slitting attacks reminiscent of Taliban-style executions.

Yet these acts have largely been treated as isolated crimes or routine political disturbances, rather than recognised as part of a sustained pattern of communal targeting. According to the Rights & Risks Analysis Group (RRAG), these murders represent “only the visible tip of a much larger iceberg of daily violence against Hindus and other minorities” that rarely makes national headlines.

What distinguishes this phase from earlier periods of unrest is the posture of the interim government itself. Rather than acknowledging the religious identity of the victims and the communal nature of the attacks, the Yunus-led administration has consistently downplayed or dismissed such motives—often even before investigations have begun. Violence against Hindu minorities has been reframed as general law-and-order problems, political violence, or worse, as exaggerations and disinformation allegedly emanating from India. This persistent refusal to name the problem has effectively normalised it.

The narrative hardened further on 13 January 2026, when Professor Yunus sought technical assistance from UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk to counter what he described as disinformation campaigns during the election period. In this context, RRAG director Suhas Chakma warned that “the attacks on the Hindu minorities during the election campaign will be dismissed as disinformation campaigns in otherwise friendly elections between erstwhile alliance partners, the BNP and the Jamaat-I-Islami.”

RRAG has cautioned that once election campaigning formally begins on 22 January, violence against Hindu minorities is likely to intensify, only to be categorised conveniently as routine “political violence,” just as large-scale attacks on Hindus in August 2024 were earlier attributed to assaults on the Awami League rather than acknowledged as communal hostility.

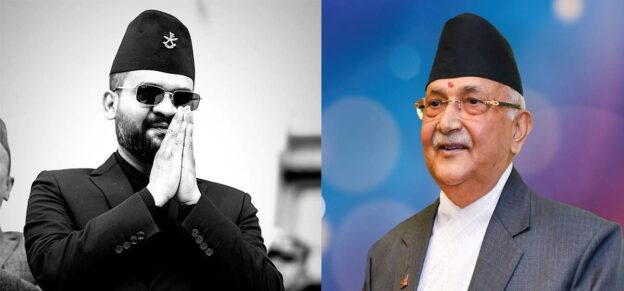

Against this deteriorating backdrop, the interim government’s repeated assurances about elections appear increasingly disconnected from ground realities. Professor Yunus has insisted that elections will be held on 12 February. A message posted on his X handle stated, “No matter who says what, elections will be held on February 12—not a day before, not a day after,” promising free, fair, peaceful, and even festive polls. These statements, reiterated to foreign diplomats including former senior US officials Albert Gombis and Morse Tan, offer little reassurance to minority communities living under constant threat. An election may be conducted on schedule, but without security and acknowledgment of violence, participation itself becomes coercive and unequal.

International observers have begun voicing concern. On 11 January, the Chief Observer of the European Union Election Observation Mission, Ivars Ijabs, called for inclusive and participatory elections involving religious minorities and ethnic communities. Yet inclusivity cannot exist in an atmosphere of fear. RRAG, in a press communiqué, has warned that Hindu minorities are unlikely to participate meaningfully in the electoral process unless the state first recognises that they are being targeted because of their religious identity and takes concrete steps to ensure their protection. The organisation has urged election observers, including the European Union, to actively monitor violence against religious minorities and indigenous communities throughout the election period.

Elections Will Be Held on February 12, Chief Adviser Tells US Diplomats

DHAKA, January 14: Chief Adviser Professor Muhammad Yunus on Tuesday reaffirmed his government’s commitment to hold the general elections and the referendum as scheduled on February 12.

The Chief Adviser… pic.twitter.com/WySGQzOPTp

— Chief Adviser of the Government of Bangladesh (@ChiefAdviserGoB) January 14, 2026

— Chief Adviser of the Government of Bangladesh (@ChiefAdviserGoB) January 14, 2026

India, too, has expressed alarm. The Ministry of External Affairs has spoken of a “disturbing pattern” of recurring attacks on minorities, their homes, and businesses, calling for swift and firm action. These concerns were met not with accountability, but with counter-accusations from Professor Yunus that India was exaggerating the violence—further eroding confidence in the interim government’s willingness to address the crisis honestly.

Domestic criticism has been equally severe. According to local media reports, the Bangladesh Hindu Buddhist Christian Unity Council has warned that communal violence is rising at an alarming rate as elections approach. Economist and public intellectual Debapriya Bhattacharya has gone further, arguing that an interim government that promised reform has instead become hostage to narrow and radical interests, failing in its most basic duty to protect citizens. He has openly questioned whether a government unable to safeguard minorities can credibly conduct impartial elections.

Bhattacharya has also criticised the government’s reform dialogue for excluding broader societal stakeholders, warning that this failure has allowed the old political and bureaucratic order to quietly reassert itself. According to him, those who once sought to build a new political arrangement have been absorbed into costly electoral processes, while entrenched interests—especially the bureaucracy—have returned as the real custodians of power under the interim dispensation.

The message from these killings is unmistakable: the death of Samir Das and fourteen other Hindu minorities is not merely a human rights failure, but a profound moral and political indictment. As Bangladesh approaches a decisive electoral moment, minority citizens are being killed, silenced, and rendered invisible—while the state debates narratives rather than responsibilities. Elections held amid fear, denial, and selective blindness may meet procedural deadlines, but they cannot claim legitimacy, inclusivity, or justice.