Chattogram, Bangladesh’s main port city and economic gateway, is facing a convergence of crises that go beyond routine law-and-order challenges. Once tightly controlled during Sheikh Hasina’s 17-year tenure, the city has entered a far more volatile phase since the Yunus-led interim administration assumed power following the mass student-led uprising of July–August 2024.

The killing of a senior Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) officer during a raid on the city’s outskirts, followed days later by an unprecedented police order barring hundreds of individuals from entering or residing in the metropolitan area, has exposed deep tensions between security imperatives, political instability, and the rule of law—at a time when Bangladesh heads toward a crucial parliamentary election. Together, these developments reveal a state struggling to assert authority in spaces where criminal networks, political patronage, and parallel power structures have long coexisted.

The immediate shock came with the death of Deputy Assistant Director Abdul Motaleb of the RAB, killed during an operation in the Salimpur hills of Sitakunda on Chattogram’s northern fringe. Authorities said a RAB team was ambushed by a crowd of 400–500 people, allegedly mobilised through loudspeaker announcements, as officers attempted a raid in the forested area.

The scale and coordination of the attack were striking. Officials suggested it pointed not to spontaneous backlash, but to organised resistance, indicating that criminal groups in Salimpur possess warning systems, manpower, and local control mechanisms rivaling the state.

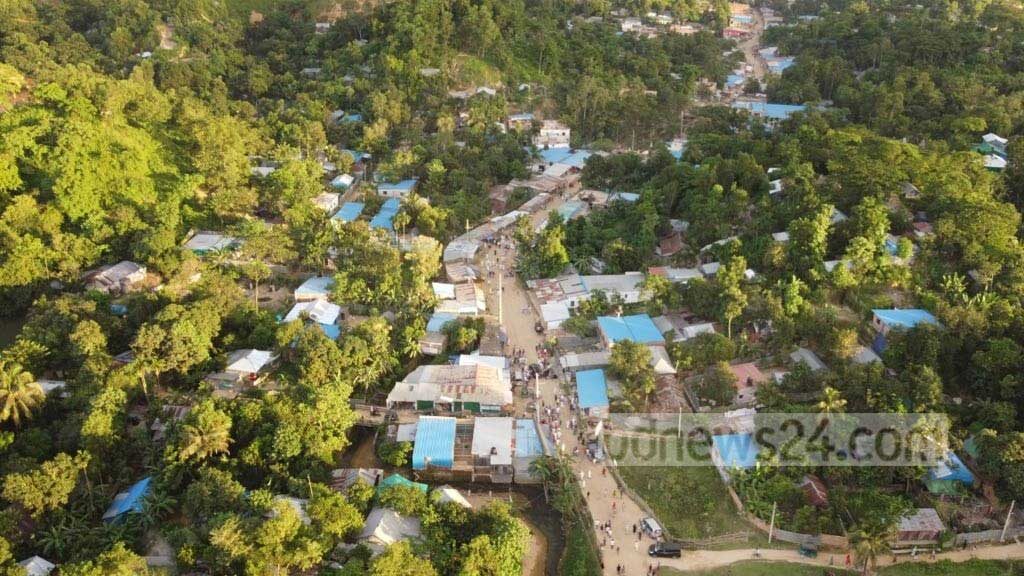

Salimpur is no stranger to notoriety. Its steep hills, much of them government-owned land, have long been illegally occupied, subdivided, and traded through networks enforced by armed groups. Entry into some neighbourhoods is reportedly regulated through informal “ID systems,” a hallmark of parallel governance. Police officers, journalists, magistrates, and now elite counter-crime personnel have all faced violence here.

The killing of a RAB officer marked a serious escalation—not merely an attack on law enforcement, but a symbolic challenge to the state’s monopoly on force.

The Salimpur incident was not isolated. Across Chattogram, violent crime has risen, particularly in areas such as Raozan, Hathazari, and Chandanaish, where political rivalry intersects with extortion rackets and control over land and sand extraction.

In recent weeks, a businessman and local political activist was shot dead near a police outpost in a brazen attack involving more than 20 bullets. Lawyers, journalists, and police officers have been assaulted in public. Organised snatching gangs have targeted shoppers during Ramadan and ahead of Eid, prompting police advisories urging citizens to avoid poorly lit streets.

Business associations warn that deteriorating security threatens commerce in the port city, which handles the bulk of Bangladesh’s international trade and is crucial for regional supply chains, including links to India’s northeastern states. Amid this backdrop, authorities opted for a dramatic preventive response.

On 17 January, the Chattogram Metropolitan Police (CMP) issued a gazette-style public notice naming 330 individuals described as “miscreants,” ordering them to leave the metropolitan area and barring re-entry until further notice. After public scrutiny revealed errors—including the inclusion of a deceased former city councillor—the list was revised to 229 names.

CMP cited Sections 40, 41, and 43 of the Chattogram Metropolitan Police Ordinance of 1978, which allow the police commissioner to restrict the movement of individuals deemed threats to public safety. Commissioner Hasib Aziz described the move as an “extra preventive step” to ensure peace ahead of elections.

What makes the order extraordinary is not only its scale, but its scope. These provisions had never before been applied simultaneously—or to such a large and diverse group—in CMP history.

The list includes alleged top criminals linked to shootings and extortion, some reportedly operating from abroad. It also names a significant number of political figures, mostly associated with the now-banned Awami League and its student and youth organisations, alongside a smaller number of local leaders from the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP).

Among those listed are former ministers, members of parliament, a former mayor, dozens of ex-city councillors, and political organisers. Several are already incarcerated, while others face multiple criminal cases, including allegations linked to the violent unrest of July. The inclusion of Chinmoy Krishna Das, a jailed leader of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), further fuelled controversy, raising questions about the criteria used to compile the list. For critics, its breadth blurs the line between crime control and political management.

There is little dispute that the CMP ordinance grants the commissioner authority to issue exclusion orders. The controversy lies in how that authority is exercised. Human rights activist Nur Khan Liton warned that bypassing arrest and prosecution undermines basic legal principles. “If the police believe someone poses a threat or has committed crimes, they should arrest them and present them before a court,” he said. “Publishing a mass exclusion list instead raises serious due-process concerns.”

Legal analysts also note that public naming without judicial oversight risks reputational harm and collective punishment—especially when some listed individuals are already imprisoned or abroad.

Security experts caution that the measure may produce unintended consequences. Retired Major Emdadul Islam warned that pushing suspected criminals out of Chattogram could simply displace them to other districts, spreading instability rather than containing it.

With the military already deployed nationwide and joint security operations ongoing, some analysts question whether such a highly visible administrative measure was necessary—or whether it reflects frustration with the limits of conventional policing. CMP officials argue that the list creates “psychological pressure” and encourages public cooperation. While such logic is common in preventive policing, rights advocates note it sits uneasily with democratic norms, particularly during an election period.

The timing of the order is critical. Bangladesh’s parliamentary election is approaching amid heightened political polarisation and international scrutiny. For regional observers, including India, Chattogram’s stability carries strategic significance—not only economically, but also for connectivity and security. Heavy-handed security measures during election periods have historically drawn criticism in Bangladesh. Although CMP insists the order is non-partisan, the predominance of figures linked to the banned former ruling party, combined with the inclusion of opposition leaders, complicates perceptions.

At the same time, the killing of a RAB officer underscores a genuine security challenge. Criminal networks capable of mobilising hundreds and killing elite officers cannot be dismissed as mere political rhetoric. Taken together, the Salimpur killing and the mass exclusion order reveal a deeper dilemma. Bangladesh’s authorities confront areas where criminal, economic, and political interests overlap, and where state authority has long been negotiated rather than enforced.

The challenge is not simply to suppress violence, but to reassert lawful governance credibly, transparently, and proportionately. Force without accountability risks normalising exceptional powers; restraint without effectiveness risks emboldening armed groups.

As Bangladesh moves toward its parliamentary election, Chattogram has become a test case of policing capacity, political neutrality, and the viability of security-first governance within a democratic framework. For India and the wider region, the outcome matters. A stable and lawful Chattogram is not only Bangladesh’s concern; it is central to regional trade, connectivity, and security. Whether the current approach restores order or deepens mistrust will shape that future long beyond election day.