If one were to describe election day in Bangladesh in a single frame, it would not be of ink-stained fingers and celebration. It would be about confusion, confrontation and, in many places, chaos.

Videos circulated through the day showing women being beaten by locals for allegedly distributing cash on behalf of Jamaat-e-Islami or the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP). Elsewhere, Jamaat activists were reportedly assaulted on allegations of ballot stuffing. In several constituencies, rival party supporters clashed openly. Violence was not hidden in back alleys; it was visible, recorded and shared in real time. That was the canvas on which Bangladesh voted for its 13th Jatiyo Parishad and in the Gono Vote referendum.

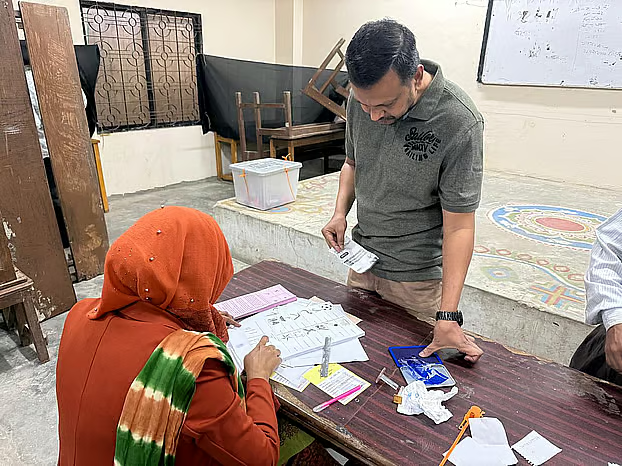

And yet, amid this turmoil, people did step out to vote. In parts of Dhaka and a few major cities, there were queues. But in many other polling stations, there was an eerie emptiness — so much so that security personnel were seen playing cricket with children to pass the time. Perhaps the most troubling common thread was this: many voters arrived at their polling stations only to discover that their votes had already been cast.

That, in many ways, tells the real story.

Yes, there was an election. Yes, ballots were printed, polling centres opened, and counting began. But can an election be called truly democratic when intimidation, alleged ballot stuffing and violence define the atmosphere? How would international election observers interpret a process where basic elements of credibility — equal participation, security of voters, neutrality of administration — appear compromised?

What makes this moment even more complex is the political backdrop. The Awami League, after 15 years in power under Sheikh Hasina, is out of the race — its registration suspended following the July–August 2024 uprising. There is little doubt that Hasina had grown deeply unpopular and that frustration among citizens, especially the youth, was real. Many viewed her rule as authoritarian. The uprising was, in large measure, an expression of that anger.

But here is the uncomfortable truth: Bangladesh’s political crisis has never been about one party alone. To single out only the Awami League for corruption, excesses or human rights violations would be simplistic. The BNP–Jamaat alliance, during its time in power, carries its own record of alleged abuses, minority persecution and entrenched corruption. The problem, as many Bangladeshis quietly admit, runs deeper than personalities.

The interim government led by Muhammad Yunus presented this election and referendum as the birth of a “new Bangladesh.” Yunus himself, smiling and optimistic, called it just that — a new beginning. He smiled confidently as he spoke of renewal and reform. But for many watching closely, that smile felt like more than optimism. It seemed calm on the surface, yet suggestive of bigger changes quietly taking shape.

And that is where the referendum becomes important. The proposed constitutional reforms, strongly backed by the interim government, could significantly reshape executive power. Some critics believe this may allow Yunus to remain central to the system, possibly even in a presidential role. They also argue that by openly supporting the referendum, the government risked appearing less neutral than it should during a transitional election.

The International Crimes Tribunal proceedings against Sheikh Hasina also continue to generate debate. Questions linger over whether the process reflected a fully neutral democratic environment and about whether it functioned as a fully impartial judicial body. Even a leaked conversation involving a foreign diplomat suggested discomfort with how the process was handled. If one seeks accountability, the environment in which that accountability is delivered must itself be democratic and beyond reproach.

Many Awami League supporters and minority communities felt intimidated in the months leading up to the polls, claiming they had little space to express dissent.

Concerns have not been limited to one side. Thousands of young Bangladeshis have openly questioned the conduct of certain self-styled youth leaders. Islamist youth figure Hasnat Abdullah was widely criticised after videos surfaced of him allegedly threatening voters. Reports of intimidation targeting minorities and known Awami League supporters added to the unease. Properties were vandalised in some areas. Fear became part of the political language.

And so the day unfolded not as a festival of democracy but as a test of resilience in a charged and polarised environment.

Bangladesh Human Rights Watch Secretary General Mohd Ali Siddiqui summed up public anxiety bluntly on television: “The people of Bangladesh are seriously worried, and consequences may follow very soon.” That sentiment echoes beyond party lines.

The Election Commission appeared cautious, even restrained. It conducted the mechanics of voting but stopped short of dramatic interventions, perhaps wary of provoking further unrest or becoming a target itself. It was a delicate balancing act — administer the vote, avoid confrontation.

Voices outside Bangladesh also weighed in. Senior Indian advocate Mahesh Jethmalani took to his social media platform X to warn that “a dangerous global game” was playing out under the cover of elections. Posting a video of alleged threats by Islamist youth leaders, he argued that when voters must choose between their ballot and their safety, the process is already compromised. Former diplomat Rajiv Dogra went further, suggesting that whether power ultimately rests with Yunus or Jamaat, the deeper concern is the direction Bangladesh is heading.

A dangerous global game is playing out in Bangladesh under the cover of elections. What should be a democratic exercise is not; it’s intimidation, extremist mobilisation, and fear-driven messaging to hand over the country to Islamic terrorists.

Islamist youth leaders like Hasnat… pic.twitter.com/zXgfMKiema

— Mahesh Jethmalani (@JethmalaniM) February 12, 2026

So what, then, has changed since Sheikh Hasina’s ouster?

That is the question hanging over Dhaka tonight.

The uprising promised liberation from authoritarianism. But many observers now worry that the vacuum has not produced stable democratic renewal — instead, it may have opened the door to a different form of concentrated power, shaped by fragile institutions, street pressure and ideological mobilisation.

Bangladesh’s election day showed both participation and paralysis; hope and fear; ballots and bruises. The country voted, yes. But whether it voted freely — and whether this marks the birth of a new democracy or the reshaping of old power structures — remains uncertain.

The ink has dried on millions of fingers. The real verdict, however, may take much longer to reveal itself.