Almost 10 months after first raising the issue in Hainan, Muhamad Yunus has once again spoken of integrating India’s “Seven Sisters” — the northeastern states — along with Nepal and Bhutan through what he describes as Bangladesh’s open seas, which are “just not borders but an opening to the world economy.” Notably, he referred to the Seven Sisters without mentioning India, even though the region is an integral part of the country.

Yunus made the remarks in his farewell address, carefully timed on the day (February 17) Tarique Rahman of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) was to be sworn in as Prime Minister, along with his cabinet, by President Mohammed Shahabuddin.

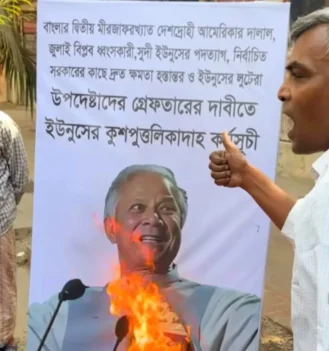

For many within and outside Bangladesh, the statement came as no surprise. Critics argue that after 18 months marked by economic strain, political tension and allegations of minority persecution, Yunus is attempting to craft an “escape route.” The period has been described by detractors as “one of the most difficult” in recent decades.

Against that backdrop, his decision to mention the Seven Sisters separately — while omitting India — and to frame his speech in strong nationalist rhetoric stood out. He claimed Bangladesh had restored its “sovereignty, dignity, and independence” in foreign policy and was “no longer tutored by others’ directives.” Many Bangladeshis, cutting across ideological lines, see this as a “diversionary tactic.”

While some observers say “little attention” should be paid to the remarks, others view them as part of “a deliberate narrative” suggesting that northeast India could function independently through Bangladeshi connectivity. International experts note that similar comments were made by Yunus in Hainan in April 2025, interpreted as an attempt to sustain Chinese interest in the Siliguri corridor.

In China, Yunus had said that the seven northeastern states of India are landlocked and lack ocean access, implying that Bangladesh alone could provide maritime connectivity. Bangladeshi commentators swiftly countered this, pointing out that the “seven Indian states have access to India’s major ports, the nearest, being Haldia Port in Kolkata, and that India’s coastline is ten times longer than Bangladesh’s, stretching approximately 7,500 km from Haldia in Kolkata to Narayan Sarovar in Gujarat?”

Others reminded him of India’s access to Myanmar’s Sittwe Port in Rakhine State through the India–Myanmar corridor.

Yunus’s comments were widely seen as an overture to Beijing for economic and possibly strategic cooperation. Critics argue that such language encroaches on India’s sovereign sensitivities and signals that Bangladesh may be open to facilitating deeper Chinese involvement in the Bay of Bengal under the banner of regional development.

India responded firmly. External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar dismissed the suggestion that India’s northeast is dependent on Bangladesh for sea access. “Cooperation is not about cherry-picking,” he said.

Despite that pushback, Yunus has continued referring to the Seven Sisters in ways that some in the region see as an attempt to blur established political boundaries. Voices in northeast India describe it as “a clear attempt to revive internal disturbance in the region.”

Prominent Bangladeshi media personality Dr Abdun Noor Tushar dismissed the remarks outright. “There is no real reason to take the outgoing chief adviser of the interim government’s statement seriously,” he said.

Speaking on the issue, Dr Tushar added that by excluding India and referring to cooperation with independent states for using Bangladesh’s Chattogram Port for the so-called “Seven Sisters,” “he has made a remark that goes beyond diplomatic norms and practical reality.”

“Over the past 18 months, we have not seen any concrete diplomacy or foreign policy initiative that would enable the Seven Sisters region to use Bangladesh’s transit facilities or its seaports—whether Chattogram or any other—for international trade,” Dr. Tushar said. “Such cooperation requires long-term agreements, regional consensus, and consistent diplomatic engagement, none of which were visibly pursued by the previous government.”

He described the former chief adviser’s statement as “more rhetorical than substantive.” Without mincing words, Dr Tushar said Yunus’s speech was “lacking policy backing and does not reflect any meaningful progress in regional connectivity or foreign trade cooperation,” adding that from a diplomatic standpoint the remarks were “questionable and detached from ground realities.”

Former Indian Eastern Command Army Chief Lt Gen (retd) Rana Pratap Kalita also rejected Yunus’s claims, saying such integration was far from straightforward. While acknowledging that India must remain cautious given the vulnerability of the Siliguri corridor, he stressed that the country is prepared to handle even veiled threats.

“This is not the first time he (Yunus) has said this,” Kalita remarked, adding that the comments reflect “his deep anti-India feelings” and amount to “singing somebody else’s tune.”

He dismissed the suggestion of incorporating the Seven Sisters with other countries without India’s involvement as “wishful thinking, something Yunus knows can never be achieved.” According to Kalita, “He is only trying to needle India as he knows that India is sensitive to the connectivity to northeast.”

Bangladesh plays a practical role in enhancing connectivity to India’s northeast, and Yunus is well aware of that reality. It is precisely this strategic geography, Kalita suggested, that he is attempting to leverage rhetorically.

International relations expert Professor Srikanth Kondapalli of Jawaharlal Nehru University believes the provocation is intentional. He argues that China has “contingency plans” regarding the Siliguri corridor, based on the assumption that if the corridor were cut off, northeastern states could drift away from the Indian mainland. “China definitely has an interest as this will weaken India,” he said.

According to Professor Kondapalli, Yunus appears eager to align himself with such thinking. If the northeastern states were economically reoriented towards Bangladesh, they would, in theory, become dependent on it as a larger regional economy.

Such remarks are unlikely to go unnoticed in New Delhi. Over the past decade, India has committed significant political and financial capital to connectivity corridors through Bangladesh, aiming to better integrate its northeastern states with the mainland.

Against that backdrop, Yunus’s framing appeared to invert the established narrative. By implying that the region’s future access and economic prospects could depend more on Dhaka’s strategic discretion than on India’s long-term planning, the speech subtly repositioned Bangladesh from transit partner to potential gatekeeper.

“It’s just a ploy to provoke India and more than that nothing is going to come out if it,” Lt Gen Kalita said. “It is best to ignore him, as in any case he was not a popular government and temporary, so now it will be on the democratically government to decide and take thigs forward and we will have to see how things evolve.”

Veteran Assam journalist and political commentator Haider Hussain shared a similar view. He said Yunus’s position has little relevance in the current geopolitical climate. Recalling the 1905 “Banga Bhanga,” Hussain noted that there had once been a plan to amalgamate Northeast India with East Pakistan, but it never materialised.

He emphasised the importance of the new Prime Minister building “a good relationship with northeast states and India,” adding that cordial ties with neighbours are essential for Bangladesh’s progress. Hussain also pointed to India’s gesture of sending Lok Sabha Speaker Om Birla to Dhaka as a positive signal.

In his farewell speech, Yunus praised his government for successfully conducting elections and highlighted ties with China, Japan, the United States and Europe, calling for strategic balance. He devoted considerable attention to Chinese-backed projects, including the Teesta River initiative near the strategically sensitive Siliguri corridor.

He also spoke about military modernisation, signalling that China had been a key partner in that sector — a development closely watched in New Delhi. His reference to strengthening Bangladesh’s armed forces to “thwart any aggression” did not name any country, but the nationalist tone of his speech has inevitably fuelled speculation about India.

Notably, there was no emphasis on strengthening ties with India, Bangladesh’s largest neighbour, which surrounds it on three sides and remains central to its trade, transit and security matrix. According to Professor Kondapalli, this omission reflects an unmistakable anti-India orientation.

He argues that Yunus’s vision of a “new Bangladesh” implicitly distances itself from the 1971 liberation legacy, which was closely tied to India. Yet both Professor Kondapalli and Lt Gen Kalita agree that geopolitical realities limit how far such rhetoric can go. Bangladesh’s location and India’s economic and military weight leave little room for dramatic shifts. “Yunus knows that he has no choice but to accept the status quo,” Kondapalli said.

The professor further contended that Yunus’s tenure was marked by two unmet objectives: reshaping Bangladesh’s historical narrative and pushing an anti-India agenda. He also criticised the promised “reforms,” calling them “a façade”. Economic growth has slowed, Bangladesh remains below middle-income status, women continue to face suppression, and electoral representation has drawn criticism, including from Jamaat-e-Islami. “This is the single largest failure of the Yunus government,” he said.

Yunus’s claims of reform and progress were dismissed by Kondapalli as “not true.” He pointed to mounting electricity dues to Indian firms such as Tata and Adani, along with Bangladesh’s broader energy shortfalls. Trade dependency on low-cost Indian raw materials remains significant, and water-sharing disputes over the Teesta and the proposed Tipaimukh Dam on the Barak river continue to shape bilateral sensitivities.

Bringing China into Teesta river management, he warned, would likely deepen mistrust in India, given the project’s proximity to the border. Such a move, he suggested, could leave behind a contentious legacy.

Professor Kondapalli believes Yunus has underestimated India’s capabilities. He cited major infrastructure and strategic investments in Assam and the northeast, including a defence corridor, semiconductor projects, expanded rail and road networks, fibre-optic systems and an underground railway line in the Siliguri corridor. With such investments underway, he said, the idea that the Seven Sisters could be separated from India remains “wishful thinking.”

With additional inputs from Kongkon Karmaker in Dhaka and Nayanjyoti Bhuyan in Guwahati