The momentum of the conflict theatre is gradually shifting and India will surely want to take a closer look and decide the future course of action.

It has been over two years since the military-led coup in Myanmar, and over 3,000 people have lost their lives since then, which includes countless number of women and children. The war between the Myanmar military junta and the revolutionary forces has escalated manifolds over the past six months, and the current trends only indicate of more fighting and more casualties. The fallout of which has made the regional security dynamics extremely complex, with huge implications for India.

India, which shares over 1600 land as well as a maritime border with Myanmar, has been treading cautiously while closely monitoring the day-to-day developments in the neighbourhood. Since the coup, the statements which have been issued by India has all been carefully worded. In fact, post the 2021 military coup, India seems to have chosen to keep its position on Myanmar somewhat mixed. Thus at one time it has emphasised, on India’s interest at the early “return of democracy” in Myanmar, whereas at other times, it completely avoided the mention of the restoration of democracy or release of political prisoners. Instead, the focus were on issues concerning security and stability along the borders and on India’s development projects in Myanmar.

At a gathering in Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University on August 18, 2022, India’s Foreign Minister S Jaishankar said that India’s relationship with Myanmar “is not something which should be judged by the politics of the day.” Clearly, the Indian Foreign Minister was alluding to the fact that as Myanmar’s big neighbour, India has to deal with the military regime in, especially when it comes to dealing with its concerns – organized crime, drugs, cross border insurgencies, human trafficking etc. India’s state position in fact goes back into the early 90s with a foreign policy shift by the New Delhi (1990) from distancing itself to now dealing with the Myanmar military. While this was a more viable option for New Delhi to persuade Myanmar to crack down on cross border militancy and flow of and arms and drugs, it was also aimed at containing China from gaining a strategic and economic foothold in Myanmar.

Of late, there has been a concerted move by the NUG, former politicians of the National League for Democracy (NLD), international groups and even intellectuals at home for New Delhi to not just stop its bilateral engagements with the Myanmar military but recognize the fasting changing political situation in Myanmar. During a recent conversation, the author, members of some Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAOs) and political actors opined that “India has become unfriendly and is not supporting democracy”.

The author stayed for a year in 2016. Credit: Bidhayak Das

However, for the Indian government, things are not as simple as it may seem to be. The power centers in South Block in New Delhi are not oblivious to the Myanmar military capabilities, with increasing suupport from China, Russia and even neighbours like Thailand which continues to have multi-faceted engagements with Myanmar. But what could be worrying or a tricky calculation is understanding the sustainability of the NUG model; after all, these are still early days.

Surely India cannot and should not ape a Thailand or China, given that the issues within its bordering states with Myanmar are far more complex and diverse. However, what must be reiterated, keeping in mind the evolving ground situation in Myanmar, is that things are different. Under the present scenario and the pace at which things are moving, there are reasons to believe that New Delhi needs to realise that a lot has changed since 2015. The pro-democracy resistance of today is different, it is more intense, focused, well-planned, decisive and with a huge section of the upper middle class involved in the fight for restoring democracy.

Fast changing ground situation

The changing dynamics on the ground does provide an opportunity, if not anything else, for the Indian government to consider opening its door to have formal or informal discussions with the NUG so as to listen to their side of the story. Such a move could only be helpful should India be confronted with a situation wherein it has to deal with an alternative dispensation headed by the NUG or a broader pro-democratic political alliance. There has been considerable number of developments which is often not highlighted in the media, particularly the Indian media. For instance, the strengthening of relationship between the NUG’s and almost a third of the powerful EAOs and how the sustenance of this alliance would play a vital role in the days ahead if the push for alternative democratic government is to succeed. There are also several other elements which has to be considered to understand the complexities of the present situation.

A recent foray by the writer along different bordering regions of Myanmar besides a visit to Yangon, revealed a hugely contrasting picture than what has been the experience of the past 12 years of stay in the country (since 2009). The takeaways from the interactions from these visits only compels one to think that it is time for a serious rethink on India’s Myanmar policy. India surely would want to be on the right side of the fence, which NUG spokesperson Nay Phone Latt (now spokesperson of the NUG Prime Minister’s Office) feels is “something that a powerful democratic neighbour must consider.”

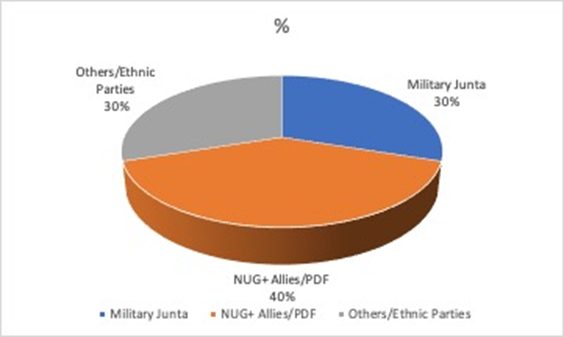

As of now, the EAO’s and the NUG combine is said to control vast swathes of territory which according to reports, is over 50 percent of the total area of the country. Reports also claim that the State Administration Council (SAC) which is under the military junta has control over less than 20 per cent confined to the three urban centres like Yangon, Naypyitaw and Mandalay.

Control of territories in Myanmar by different actors, including military junta based on several assessments and claims made by various groups. (Assessment based on a survey by the author and statistical/data analysts).

The NUG’s armed wing, the Peoples Defense Force (PDF), along with other local PDFs (LPDFs), guerilla groups and ethnic rebel fighters have been relentlessly launching successful armed assaults on military bases and on Tatmadaw soldiers spread across the different states and divisions. NUG’s acting president Duwa Lashi La, during a speech on September marking the one year anniversary of the declaration of a people’s defensive war against the junta, stated that as many as 300 PDF battalions are operating across the country, with People’s Defence Teams (PaKhaPha/PDTs) formed in as many as 250 townships.

The PDFs, LDFs and PaKhaPha/PDTs have been able to expand their footprints in the central region which is also known as the Anywar theatre of conflict and is said to have become the prime centre of public resistance. The Sagaing region which shares borders with India has been taken over by the NUG, with its own governance system replacing the military junta led government establishments. A District Command centre, a People’s Administration Coordination Committee, has been established by the NUG, which is running schools, teacher training, and health care services.

A senior PDF leader explained the formations of the armed resistance as consisting of a Central Command and Coordination Committee (C3C) which includes the NUG, the Kachin Independent Army (KIA), the Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP), Chin National Front (CNF) and the All Burma Students’ Democratic Front (ABSDF), and another Joint Command and Coordination (J2C) formed between the NUG and the Karen National Union (KNU) to oversee all troop operations in areas under the KNU’s control. These formations have been jointly set up by the NUG and its EAOs alliance partners to oversee the operations of the PDFs. Besides, the PDFs, there are others groups separate from the LDFs and the PDTs, such as the Chinland Defence Force (CDF), Karenni National Defence Force (KNDF) and Kachin People’s Defence Force (KPDF). These groups are extremely localised and powerful and operate under the C3C but do not align with the NUG and its policies.

Makings of a common goal and building a political consensus

Inside the country, there are telltale signs of divisions within the military and the mood among the people seems to lend a semblance of reliability to the general claims one gets to hear that “the military is gradually losing the war.”

From planting informers inside the military (with help of international support) who are popularly referred to as “watermelons” – green from the outside and red – the colour associated with the NLD – from inside, to getting the general masses to boycott military businesses and military supported consumables, the NUG certainly has been making other forms of gains in addition to its armed exploits. A senior journalist and a close associate told this writer in Yangon recently that “There’s a complete boycott of the highly popular Myanmar Beer and the Red Ruby cigarettes by all, people are refusing to pay electricity bills. Everyone including many local businesses which once worked closely with the military are refusing to cooperate with the SAC,”

However, the NUG has an uphill task ahead as the takeover of the military may not be as easy as it has been made out to be. The NUG aspires to put together a “Federal Army” combining all the armed groups, including the PDFs. However, given the contrasting interests among the various ethnic groups in Myanmar, cutting across distinct geographical, political, historical, cultural and even religious divides, the task will be daunting if not impossible. Besides many ethnic armed groups, do not still share a common response to the coup. The Arakan Army (AA) has refused to entertain any civil disobedience movements or protests in Rakhine and instead chose to enter into ceasefires with the military junta. Though on the other hand, it has also been involved in training PDFs and supporting a “common agenda”.

The larger common goal – to throw out the military and restore democracy, under a Federal Union, has been instrumental in the stitching together of the NUG-EAO alliance. Most of the differences appear to have been set aside for now, giving way to achieving this one “common agenda” before the 10-12 out of a total of 17 different big and medium sized EAOs. NUG spokesperson Nay Phone Latt, viewed this as “the key to a broader settlement.” During a conversation with the author, he seemed to be confident that “ethnic groups will settle down by themselves,” and all that needs to be thought about at this juncture is “to make the NUG model, however interim, as the springboard to reach “the common goal.”

As of now a third of the EAOs with a total troop strength of about 50,000 which includes groups like the BPLA and the KNU faction, the Kawthoolei Army are working closely with the NUG, while a third have extended partial support. The rest which forms about 8 percent are still in talks with the junta.

The question is, would the groups sitting outside become stumbling blocks in achieving the plans? KNU spokesman Padoh Saw Taw Nee was of the view that, “these forces would also gradually move towards a common solution, or else have to face a backlash from their own people.” In fact, powerful EAOs like the KNU and KIA which form the backbone of the partnership with NUG are also seen as the “most reliable troubleshooters” capable of getting every group under the same platform. The role of the National Unity Consultative Council (NUCC) also assumes great significance in that its very composition – members of the National Parliament which is also called the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), currently serving as the interim legislature (and largely comprising NLD members), the NUG as the executive, EAOs, ethnic political parties, members of Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) groups, general strike councils and civil society organisations – has been done with the intention of developing a political consensus which includes all relevant processes from the federal charters to the transition constitution and the proposed structure of an interim government.

Perhaps this gives all the more reason for India to rethink, which is not to suggest a disruption in diplomacy with the Myanmar military regime. As former Indian Ambassador to Myanmar, Gautam Mukhopadhaya says, “As a neighbour India has its compulsions, but we must not be seen as competing with China. We have to use our own strengths and help the people of Myanmar.” What would be worth exploring are new opportunities for New Delhi to win back the confidence of the pro-democracy forces, and most importantly the people of Myanmar.

The different groups which the author met, appeared visibly disappointed at India’s position on Myanmar, particularly the continuing engagements with the military junta. Allegations such as “India’s policy towards Myanmar has changed,” or “India does not care for the people of Myanmar,” reverberated across interviews with NUG, political and ethnic armed groups. Notably even as questions continued to be raised regarding India’s policy on engaging with the military junta, the tone of disappointment were laced with hope that India stands with the pro-democracy voices as “India’s voice in the international arena matters.”

Most speakers even acknowledged India’s concerns arising out of cross border insurgency and organised crime along largely affecting its North East states, but they also believe that India’s over dependence on the military will be counter-productive. According to them, the protection provided by the military junta to Manipur’s Valley Based Insurgent Groups (VBIGs) who have adorned the role a “junta backed militia” inside Myanmar is one of the many examples of a “deceitful and untrustworthy,” force. Burmese intellectuals believe that depending on the military to help in solving cross border insurgency, drugs and crime is “as good as a blindfold hitting the target.” A categorical reference is made to “Operation Sunrise,” which was jointly conducted by the Indian army and the Tatmadaw to hit militant camps, including those belonging to the AA along the India-Myanmar border. “What happened, the Rakhines are angry, the AA has turned hostile and this is adversely affecting India’s investments in Kaladan,” Rakhine politician U Htun Yin says, as if to describe the general belief among the reasonably well-informed section of the Burmese society.

The next six months will be crucial for Myanmar and also countries that are engaged with the process of democratic transition directly or indirectly. In this situation, it is extremely important for India to play a decisive role. Informal outreach with the NUG and EAOs would help India to leverage the goodwill which it still has amongst a large section of the people of Myanmar. It would also help lessen, if not remove, the angst and visible disappointment which is building against the present policy of engaging with the military junta or for allowing state owned companies to supply hardware to the military junta to develop its arsenals. Besides, any form of outreach will also help provide the much needed space to assess the fast developing ground situation and the shift in momentum.

During the interactions many speakers even underscored the need for India to realise this, for future relationship building and helping it address its concerns along North East India. NUG spokesperson Nay Phone Latt, brought up the necessity for India to “start engaging with the NUG,” which he feels could also provide sufficient space to curb Chinese ambitions and disruptions to Indian interests and investments in Myanmar.