In the midst of our pursuit of external success and material achievements, it’s easy to lose sight of what truly matters: our inner well-being. Even though we come to realise time and again that it is in fact, the foundation upon which our lives are built and its quality determined, yet, its often given a secondary place. We often prioritise the fancy, lofty aspects of our lives – our careers, relationships, and possessions – without ensuring that the base upon which they rest is solid. More often than not, when emotional and mental well-being is compromised, everything else begins to crumble. We become vulnerable to stress, anxiety, and burnout, and our relationships, work, and overall quality of life suffer.

Across cultures, religions, and continents, meditation has been recognised as a universal tool for strengthening this foundation – a practice that allows us to tune into our inner voice, calm our mind, and unlock our full potential. Despite the overwhelming evidence supporting the benefits of meditation, we still neglect to prioritise it in our daily lives. We get caught up in the hustle and bustle of living, convincing ourselves that we’re too busy or that meditation is a luxury we can’t afford. Sometimes, what stops us is the feeling of intimidation by the idea of meditation, unsure of where to start or how to “do it right”. Not being an exception to any of these, I was caught in the same conundrum until I exercised my conscious agency to effect a positive change.

A few years back, I stumbled upon a documentary featuring a renowned IPS officer’s tenure as in-charge of Tihar Jail, India’s largest prison. The documentary highlighted an innovative ‘experiment’ where Vipassana meditation was taught to inmates as a reformative measure. The transformative impact on the inmates, as evident from their experiences and feedback, left a lasting impression on me. This exposure sowed the seeds of curiosity, and I yearned to learn and experience Vipassana meditation firsthand. However, life’s distractions and priorities took over, and the desire simmered on the back-burner. Years went by, until destiny, or perhaps sheer serendipity, rekindled my interest. This time, I decided to take the leap, and my quest to explore the depths of Vipassana meditation led me to Namsai, where the state’s only Vipassana meditation centre is nestled.

Home to ancient temples, monasteries, and cultural institutions, Namsai is a picturesque district in the eastern part of the state. It is the land of the Tai-Khamti community, known for their rich cultural heritage, warm hospitality, and vibrant festivals. Tucked away in a tranquil haven, about half an hour from Namsai’s bustling town centre, the Vipassana centre’s peaceful ambiance and stunning natural surrounding is a perfect sanctuary for meditation and self-reflection.

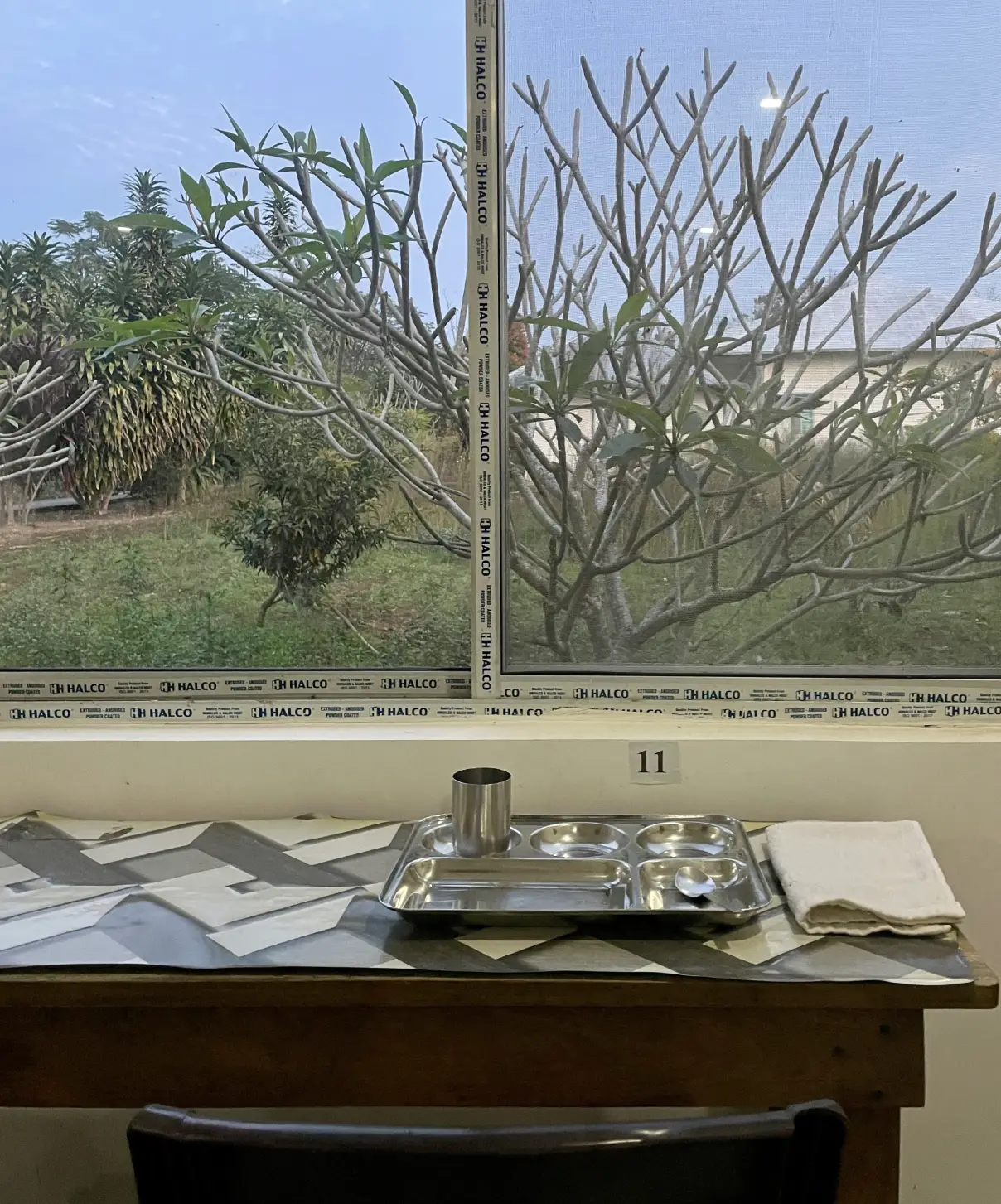

The Vipassana meditation course spans 10 days, with arrival and departure days adding up to a total of 12 days at the centre. What’s remarkable is that this transformative experience is offered completely free of cost. While this may come as a surprise, the centre operates solely on voluntary donations and contributions from past participants, driven by a spirit of generosity and a desire to enable more people to benefit from this life-changing practice. The meditation centre’s compound is thoughtfully divided into two separate sections for males and females, each with their own designated dining areas. While the main meditation hall, known as the Dhamma Hall, is a shared space, it features separate areas for men and women, fostering an environment conducive to introspection and contemplation.

Upon arrival, we completed the registration process which included surrendering our mobile phones; we wouldn’t get them back until the last day of the retreat. This was a great move towards a refreshing digital detox. On completion of these formalities, we were assigned our living quarters, consisting of simple single rooms, with some shared by two participants when the centre was at full capacity.

Before the meditation course began, we received a comprehensive briefing outlining the course’s three-part structure:

1. Anapana: Focuses on observing the breath to develop concentration and calmness.

2. Vipassana: Involves observing the body’s sensations to develop insight into the impermanent and ever-changing nature of life.

3. Metta (or Maitri): Cultivates loving-kindness, compassion, and empathy towards oneself and others.

We were also guided to strictly follow the five precepts:

1. Abstain from killing any living being.

2. Abstain from stealing.

3. Abstain from sexual activity.

4. Abstain from telling lies.

5. Abstain from all intoxicants.

Additionally, we were required to sincerely observe “Noble Silence”, which entailed:

- Refraining from talking, whispers, gestures, or any form of communication.

- Avoiding writing notes, letters, or any written communication.

- Minimising physical contact and eye contact to maintain focus inward.

Our day began at 4 am and the first meditation sitting started sharp at 4:30 am at the main Dhamma hall. The rigorous meditation regime that spanned about 12 hours a day was punctuated by breaks for rest, daily chores, meals, and concluded by 9:30 pm. Notably, dinner was not a part of the routine, yet I never felt hungry. Instead, my body felt noticeably lighter, and it seemed that the omission of dinner was indeed working and beneficial as intended. Simple vegetarian meals were served for breakfast and lunch, chosen for their objective benefits: they’re healthy, easy to digest, and respectful of diverse dietary traditions, as almost all religions have no restrictions on vegetarian food. Although being vegetarian is not a prerequisite to practice this meditation. The course is truly inclusive, welcoming all individuals in both theory and practice.

The 10-day Vipassana journey was a transformative odyssey into the depths of my mind. Far from a linear progression, it was a dynamic dance of calm and turmoil, focus and distraction. Some days, turbulent thoughts, emotions of all sorts with varying ranges of intensity, and restlessness held sway. Somedays, even innocuous sounds became overwhelming distractions. A fellow meditator’s loud laboured breathing or jarringly loud swallowing of saliva (perhaps due to discomfort or probably a nervous habit), someone breaking their knuckles (probably unaware), or someone snoring (likely struggling to adjust to the new routine) would become much amplified, exposing the fragility of my mental state. Memories, both poignant and mundane, would arise unbidden, as would random flashes of imagination and humour, making me have an intense urge to laugh or smile. Yet, amidst these fluctuations, there were also moments of remarkable clarity and control. I could follow through the meditation instruction thoroughly and my mind would settle like a calm lake, reflecting the serenity of the present moment, and I’d experience a deep sense of inner peace. The unpredictability of my mental state was humbling, as a promising morning meditation session could give way to a distracted evening, or vice versa.

As I tried to navigate the twists and turns of my Vipassana journey, I began to grasp the profound philosophy underlying the ancient practise. At its core lies the truth of impermanence, Anicca (pronounced uh-nee-chuh). The understanding that everything is in a state of constant flux, and that attachment to anything – thoughts, emotions, or physical sensations – is ultimately futile. It teaches that as long as we inhabit a human body, with our five senses constantly processing inputs and creating perceptions, feedback loops and reactions, leading to cravings and aversions, we are trapped in a cycle of suffering. This cycle begins with sense contact, where one of our senses come in contact with an external object, giving rise to a feeling. The mind then recognises and interprets this feeling, leading to mental formations of craving, aversion, or ignorance. These mental formations are the root cause of our sufferings, not the external objects by themselves. By understanding this process, we can see how our reactions to sensory inputs and experiences perpetuate the cycle of suffering.

The teachings emphasises the importance of cultivating ‘mindful awareness’ through Vipassana to break free from this cycle. By observing our experiences without becoming entangled in them, we can respond more skillfully to life’s challenges. These imprints of craving (intense yearnings, addictions, desires and attachment to pleasant experiences, thoughts, emotions, driving one to seek and cling to them), aversion (intense dislike or resistance to unpleasant experiences, thoughts, or emotions, driving us to push them away or escape from them), and ignorance (refers to a fundamental misunderstanding of the true nature of reality, including the self, impermanence, and the causes of suffering) becomes deeply ingrained, extending beyond the conscious mind into the subconscious. It influences thoughts, emotions, and actions in ways that might manifest as “patterns” and seem even “out of control” on the surface.

The key to liberation lies in not letting these aversions, cravings and ignorance take over. By mindful awareness of ‘Anicca’ (uh-nee-chah) we can take active control of our reactions – not just at the outward level of physical or verbal actions but more importantly, at the thought/mental level. I realised my experiences, with all their ups and downs, were a perfect testament to this philosophy. Reflecting on my experiences, I noticed that certain encounters in life had instilled a deep-seated sense of disgust and aversion within me. But as I sat down for consequent meditation sessions with a careful reminder of the new awareness, it changed how I experienced the same range of emotions. I learned to observe these feelings of aversion and disgust with detachment or without getting entangled in them, seeing them arise and pass away without judgment, like fleeting clouds in the sky.

I recall a pivotal moment when I sat for two hours straight without even twitching a bit, meditating, achieving a sense of stillness and calm. But the next day when I craved to replicate this success of the previous day, I realised that my desire to repeat a successful session was, in fact, an attachment to a specific outcome. Similarly, my resistance to an unsuccessful session was also an attachment. I understood that attachment to success and aversion to failure were two sides of the same coin. This insight was liberating, allowing me to embrace the impermanence of each moment, whether good or bad.

With the end of each meditation sitting and at the closing of each day, we were guided to seal our practise by centring ourselves into a state of equanimity, to make ourselves empowered and capable of emanating and radiating a sense of compassion for all, wishing well-being, peace, and happiness for all living beings – friends and foes, acquaintances and strangers, alike. This compassion is not an egocentric pity, where we condescend by deeming other’s lesser and ourselves superior. Nor does it involve negating the existence of harm or evil, for that would be a denial of reality. Instead, compassion arises from within, as a natural and effortless expression of our being. It is about cultivating compassion, not necessarily because we perceive others as pathetic or needy; rather, it overflows from us as an inherent part of who we are. A pure form of compassion which is not an agenda driven instrument of one’s ego. A compassion which does not need an externalised origin through stimulus or triggers, but comes purely from within. This state of pure compassion wasn’t easy for me to arrive at, but as the days progressed and I dedicated myself to the practice, I had a fleeting taste of it. Sometimes it requires striking the tricky balance of acknowledging the harm or evil done to us or existing out in the world, without becoming consumed by aversion or anger. It was emphasised in the discourse that as we strengthen our practice, compassion would arise more effortlessly and naturally.

Teachings about ‘karma’ and ‘Saṅkhāra’ empowered me to see myself and others with clarity, compassion, and empathy. Karma, the universal law of cause and effect, reminds us that every action, thought, and intention has consequences that shape our lives and the lives of those around us. This ancient principle suggests that our past choices and deeds influence our present circumstances, and our current actions will, in turn, determine our future.

Saṅkhāra, on the other hand, refers to the complex conditioning of our minds by our good as well as bad volitions (thoughts, emotions, and actions shaped by our free will, intentions and agency), past experiences, biases, cultural influences, and even genetics. This conditioning affects our perceptions, emotions, behaviours, and choices, often operating beneath our conscious awareness. By recognising the role of Saṅkhāra in our lives, we can begin to break free from the patterns and conditioning that no longer serve us.

Recognising the interplay between karma and Saṅkhāra, we begin to see how our actions, choices, and conditioning shape our lives and the lives of those around us. This profound insight enables us to take responsibility for our actions, let go of blame and victimhood, and aim to rid ourselves of harmful patterns and conditioning. Through Vipassana, we were taught to focus on the one thing we can truly control-Ourselves. And in the process, cultivating greater awareness, wisdom, and compassion, not only for ourselves but also for others. It teaches one to accept the fact that trials and tribulation are inevitable and a precondition of human existence. But what one has to strive for is equanimity, through all the vicissitudes of life and ultimately, liberate oneself from all cravings and aversions that keep us tied to the repetitive, vicious cycles of life and death.

What I find truly remarkable about Vipassana meditation is its refreshing absence of dogma and sectarianism. It does not concern itself with the question of who the only “true” God is, nor does it vouch to be the sole proprietor of “tickets to heaven”. As the revered teacher S.N. Goenka often emphasises, Vipassana is neither intellectual entertainment nor a devotional exercise. Rather, it’s a practical, experiential journey into the depths of our consciousness through the mind-body framework. By observing our thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations without attachment or aversion, we can develop a profound understanding of ourselves and the world around us. While I was a part of the course we had Buddhist monks, practising Christians, Hindus and followers of indigenous faith in the retreat (I found out only through casual conversations at the end of the retreat, no religious profiling is done in any way).

It brings the human race together and concerns itself with the shared ‘condition’ or state of being human and the inevitable part of it- misery. Misery sees no region, religion, caste or race and it is amusing to me that no matter how many differentiating categories of “us” and “them” we create, misery feels exactly the same for all of us.

Pagoda, with separate cells inside for solitary meditation. (Photo credit: Dhamma Aruna management.)

Pagoda, with separate cells inside for solitary meditation. (Photo credit: Dhamma Aruna management.)

What struck me was a point made in the discourse as to why we do understand a lot of things on the intellectual level but it slips away like grains of sand and passes us by, and ultimately the knowledge does not make any substantive difference in our lives whatsoever? Indeed, on an intellectual level we all know “forgive & forget”, “mind over matter’’, “past is dead, future does not exist yet, all we have is now”, “we all die in the end, we don’t know when”, etc that these have become clichés. But on the experiential level we grapple with fear, hatred, unhappiness, yearning for happiness, aversion to pain, ruminating over pain, holding onto happiness and the fear of losing it – basically the whole range and hues of misery. Vipassana meditation offers a profound shift. By cultivating experiential understanding through direct observation of our thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations, we can begin to bridge the gap between intellectual knowledge and actual transformation. Through this practice, we can develop the wisdom and compassion needed to navigate the complexities of human suffering. And perhaps, in this journey of discovery, we may uncover the greatest truth of all – that true freedom lies within.

The discourse by the teacher often mentioned three ways of gaining knowledge:

- Suta-Mayā-paññā: Knowledge gained through hearing or reading.

- Cintā-Mayā-paññā: Knowledge gained through thinking, reasoning, and intellectual understanding.

- Bhavana-Mayā-paññā: Experiential Knowledge, gained through direct experience and personal practice.

Theoretical understanding is merely the first step. To truly grasp the depths of Vipassana, one must experience it directly. As the ancient wisdom of ‘Bhavana-Mayā-paññā’ reminds us, true wisdom arises from direct experience, not mere theory. Isn’t it true indeed that no amount of intellectualising, thinking, understanding and learning about swimming or even sitting by the river can teach us to actually swim until we get down into the water?

I can only share my humble understanding and experiences of Vipassana philosophy and practice, gained through my limited insights and capacity. I encourage each of you to explore it for yourself, as it may yield even more profound benefits than my own experience. As reminded in the Vipassana discourses, no two experiences can be identical. Each person’s unique set of thoughts, Saṅkhāras, and karmas shape their experiences, making every journey distinct. I offer my story not as a benchmark to measure your progress, nor as a guarantee of what to expect but rather as a sharing of my personal experience. I hope you’ll consider it without judgment, not rejecting it merely because you can’t relate to me or find it uninteresting. Instead, may it inspire you to embark on your own journey of discovery and transformation.

About two weeks after leaving the centre at the time of writing this article, I’ve entered the next phase of my journey: integrating the practice into daily life. I’m eager to experiment and learn how to apply the insights I gained. While I anticipate challenges, I’m looking forward to this new chapter. As I see it, the ultimate test of any religion or spiritual practice, including meditation, is its ability to translate into tangible, positive changes in our life and, more profoundly, in who we are as a person. If it doesn’t, then what’s the point? It becomes mere hollow acts or going through the motions. And if you see me stumbling or struggling along the way, just know that I’m trying. That’s all any of us can do – take each step with intention, learn from our mistakes, and keep moving forward. It’s been a beautiful start to the year for me. Wishing you a transformative journey ahead, filled with peace, clarity, and freedom.