“To forget how to dig the earth and to tend the soil is to forget ourselves.”

– Mahatma Gandhi

Soil is a living entity and connector to living beings including humans. Civilization grows and sustains because of the quality of soil. Ecosystem people, living close to nature, have immense observations about every element of nature, including soil. There is adaptation of fuzzy logic by repeated observations and trials by the ecosystem people to characterise the soil and make decisions of land uses based on its soil quality.

It was an early morning of November 2022 while walking in Samparidisa, going to the jhum cultivation site, my mentor from the village Debkanta Debragidi (he was the village head at that time and aged around 70 years) was with me along with two young interlocutors from the village. We crossed a bamboo grove followed by a patch of forest and while crossing a stream on the way in the forest we observed a deep black layer of soil. A question came to my mind and I asked Debkanta da, “how do you identify soil quality to make decisions for your farming?”

He just laughed (as he normally used to in response) and said “it is part of our life, soil takes care of reproduction, that’s how our crop grows, we always observe and try to verify its quality in our own ways as it was learnt from our parents; when I started practices of jhum at my young age with my parents, that exposed me to this (to verify soil quality). Everyone needs to learn it, if they want to live with nature and sustain through farming practices.”

He paused and added, “Let’s go. Ahead we will discuss after we return from this walk.”

I was quite sure that Debkanta was going to give me another lesson on soil, as he had done earlier. I felt emotional listening to his allegorical interpretation of soil and reproduction. It reminded me of a scholar’s interpretation of SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and its direct link to soil. I was looking forward to a longer discussion on soil with Debkanta da and the other elders, as he often facilitated such dialogues.

In Samparidisa, I used to stay in the house of Chutendra Langthasa, teacher of the Primary School of Samparidisa. Normally, except for long holidays, his family members stayed at Haflong for his son’s education, who was in class nine at that time. In Samparidisa there is no high school nearby, so children need to go out from the village and stay in other places for their education from secondary level onwards. Langthasa became like my brother, he is also a very sensitive person and has profound knowledge about their tradition and culture. My long and frequent visits to the village from 2021 created a strong bond with the family of the Langthasa. Their kitchen is now open to me and I can cook anything if I want to.

When I reached the place of my stay after a long walk through the jhum scape, I was tired, sunlight falling through the Samprai plant spiraled through the leaf of the areca nut plant in the courtyard. Langthasa was in school, the door was slashed from outside, no one uses lock and key here. There is no question of stealing something from someone’s house. I just opened the main door and entered the house. After taking off my jacket, I felt like taking a shower, and planned to prepare for the next course of work (preparing my observation note). After the shower, I went to the kitchen to prepare a cup of tea and sat in the courtyard with my notebook.

I don’t know how much time passed before I heard someone ask, “Did you take lunch?” It was Hembinon. I gestured “not yet.” He replied, “All right, I will warm it. Have the food; they will come.” I wondered who “they” would be. When Hembinon called me, I went to the kitchen and ate.

Afterwards, I saw Debkanta da sitting in the courtyard with Prabin and Khimpho, my young interlocutors and facilitators in the village. They were arranging something. Khimpho asked me not to come yet: “Let us arrange everything, then we will discuss.”

A while later, they called me. I observed nine different soil types displayed on a piece of paper, each labeled with its name. They had collected samples for the discussion. The soils were Hagisim (black soil), Hagajao (red soil), Hama(clay soil), Hajeng (sandy soil), Hahain (mixed soil), Jidab (moist soil), Longmaisa (stony soil), Hagrain (dry soil throughout the year), and Kainsurikhetu (soil with earthworm cast). They interpreted each one.

I asked spontaneously, “How do you identify them?” Debkanta da laughed again and said: “You need deep observation and resonant feeling to identify soil. We develop this through long practice. We look at color, texture, moisture, and water-holding capacity. We rub it in our hands, feel it, and observe if it leaves a colored mark.”

I recalled how M.D. Omprakash Sir taught us to use similar rapid identification methods during fieldwork in my days at the Indian Institute of Forest Management. Communities too practice such methods, enriched by traditional wisdom.

Debkanta da started further explanation—each of these soils has different uses. Hagisim is ideal for jhum (shifting cultivation) and homestead gardens to grow vegetables; Hagajao is ideal for earth filling and for construction purposes (like plinth of the houses, village road etc.); Hama for paddy cultivation on wet terraces, mud plaster of walls in the houses; Hajeng where water percolates easily, is ideal for potato and radish cultivation; Hahain is ideal for other crops like corn, millet, beans, etc., and also for plantation of trees; Jidab for wet paddy cultivation; Longmaisa for broom grass, bamboo, banana, pineapple plantation and also for plantation of trees that require less water; Hagrain for pineapple plantation and Kainsurikhetu ideal for jhum.

It’s an approach of resilience of development, each of the soil categories is suitable for different types of uses and it is explored and established by the indigenous community.

I just asked whether this is a soil categorisation prevalent in Samparidisa. They said, “No, you visit any Dimasa village and talk with people, they will share similar categories of soils. It is a Dimasa approach to soil classification.”

They also shared that from regeneration perspectives Hahain, Jidab, Longmaisa, Hagrain and Kainsurikhetu are the best. Later on, I walked with Debkanta da, Prabin and Hembinon for four days in the entire village area to collect soil samples and geotag different areas belonging to different soil categories. The laboratory testing of these nine categories of soil of Samparidisa revealed that Hahain, Jidab, Longmaisa, Hagrain and Kainsurikhetu soils had high concentrations of Organic Carbon with a range of 1.51 to 3.07%. It indicates perfection in communities’ observations about quality of soil. Such results illuminate the richness of the traditional knowledge system and its practicality to develop the spirit of life with nature.

Learning from the community through participatory principles is a long-term process, there is no shortcut to de-learning and relearning. I am fortunate enough to participate in a ‘de-school’ programme under the approach of alternative worldviews of Heinrich Böll Stiftung, India to carry out long-term study in this village.

My first visit to Samparidisa was in 2004 and subsequently in 2011, 2012 and in 2021, 2022 and 2023 (during de-school and post-de-school process). After long interactions, people understood my interests, queries, and the journey of learning actually took place under the guidance of village elders and with support from young interlocutors and facilitators.

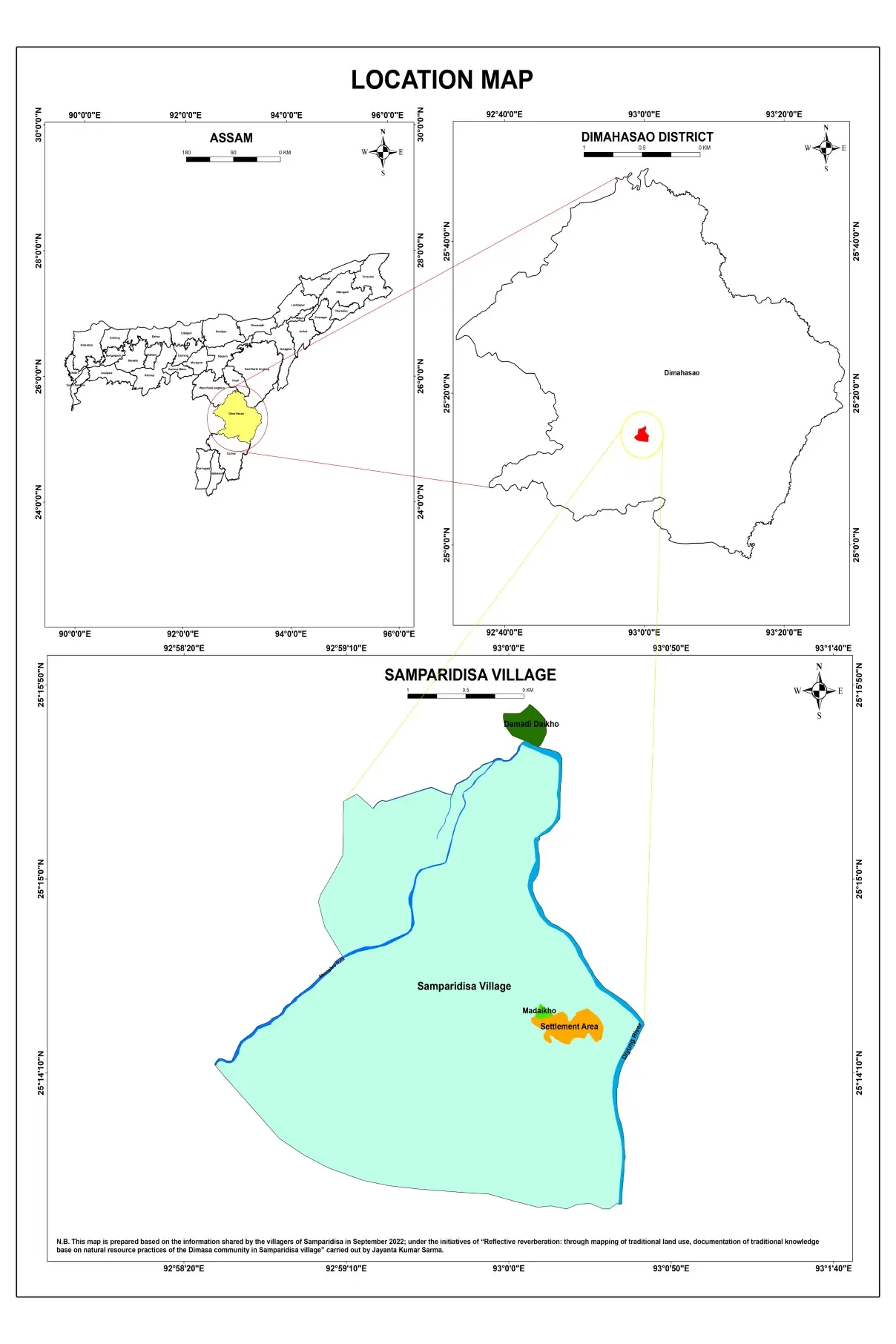

More than 100 years old, Samparidisa is a Dimasa heritage village of Dima Hasao district of Assam. It is a museum of living traditions. It is better to develop this village as a place of learning for the traditional knowledge system.