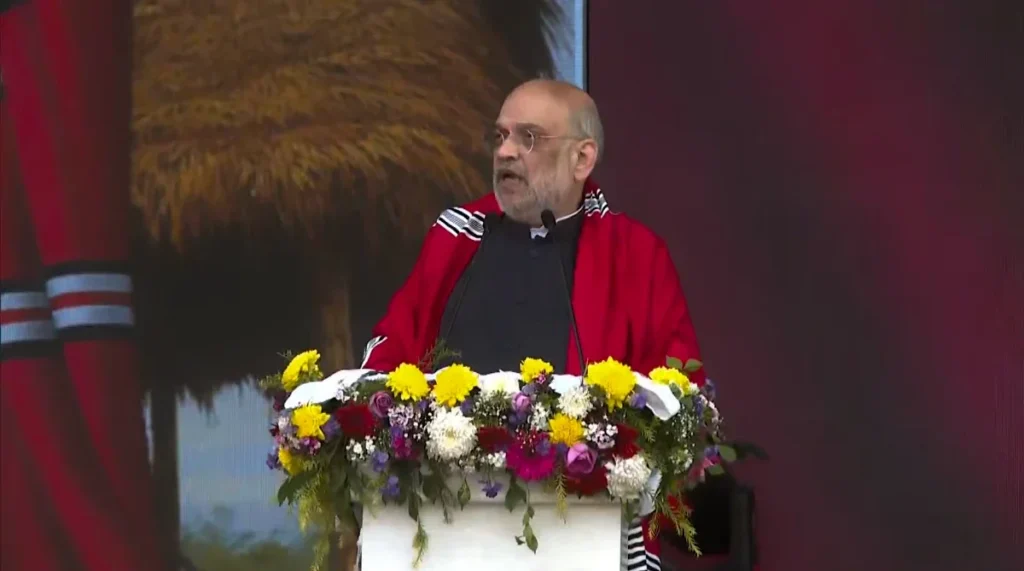

The foundation-laying ceremony of Assam’s second Legislative Assembly complex in Dibrugarh, led by Union Home Minister Amit Shah, was projected as a landmark moment in decentralised governance and infrastructure-led development in Upper Assam. Framed by the state government as a historic shift away from Guwahati-centric administration, the event was also marked by the inauguration and announcement of multiple high-value projects spanning governance, sports infrastructure, wildlife conservation and flood management. Yet, beyond the focus on progress and institutional expansion, the visit also offered insights into the political and social currents shaping Assam’s immediate future—particularly as the state moves closer to the next Assembly election.

The timing of the event is politically significant. It unfolded against the backdrop of long-pending demands for Scheduled Tribe (ST) status by six indigenous communities of Assam—Tai Ahom, Moran, Matak, Koch Rajbongshi, Chutia and Tea Tribes. Despite repeated assurances across successive governments, constitutional recognition for these groups remains unresolved. For many within these communities, the prolonged wait has translated into growing frustration and political fatigue. What began as a demand rooted in historical marginalisation and social justice has gradually evolved into a sensitive fault line, shaping perceptions of representation, rights, and trust in political processes.

While the government foregrounded large-scale development projects and symbolic initiatives such as establishing a second capital in Upper Assam, the Dibrugarh programme did not offer a concrete timeline on the ST status issue. This absence was noted by observers even as they acknowledged the scale and ambition of the infrastructure commitments being announced. The broader sentiment is that development initiatives, however significant, are most effective when accompanied by parallel progress on identity-related concerns such as constitutional safeguards, land rights, and ethnic accommodation—issues that continue to hold deep resonance in Assam’s political landscape.

Another dimension of the political messaging surrounding the visit involved renewed emphasis on border security and infiltration—an issue that has long featured prominently in Assam’s public discourse. Amit Shah’s references to these concerns were interpreted by some as early electoral signalling, while supporters view them as a reiteration of longstanding policy priorities. In a demographically sensitive state like Assam, such narratives inevitably intersect with social anxieties, highlighting the challenge of balancing security imperatives with equally pressing concerns around employment, indigenous land protection, and inclusive development.

The Dibrugarh visit also carried unmistakable electoral signals. From the same platform, Amit Shah formally declared Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma as the leader under whom the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) will contest the next Assembly election scheduled for April. The choice of venue was symbolically significant. Dibrugarh is the constituency of former Chief Minister and senior BJP leader Sarbananda Sonowal, who currently serves as Union Minister for Ports, Shipping and Waterways. Making this announcement in Sonowal’s political stronghold sent a clear message about leadership consolidation within the party and the centrality of Sarma’s role in shaping the BJP’s electoral strategy in Assam.

This assertion of leadership comes at a time when the BJP is navigating multiple, often intersecting narratives—development, identity, security and welfare. Sarma highlighted achievements ranging from bridges and medical colleges to sports infrastructure and environmental projects. The ₹284-crore Legislative Assembly complex, the ₹292-crore Institute of Wildlife Health and Research at Dinjan, the expansion of Khanikar Stadium and the ₹692-crore wetland restoration project were all presented as markers of Upper Assam’s transformation. Together, these initiatives reflect substantial investment and a clear intent to institutionalise governance and economic growth beyond the state capital.

Yet Assam’s political history suggests that infrastructure alone cannot substitute for trust-building. The state’s past is shaped by prolonged movements, accords and negotiations centred on identity and belonging. The coexistence of ambitious development projects and unresolved identity demands underscores a persistent tension in Assam’s governance landscape—material progress has not always been matched by social consensus. Addressing long-standing concerns of indigenous communities in a transparent and time-bound manner remains crucial to ensuring that development is perceived as inclusive rather than transactional.

The broader national context further amplifies this reading. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s frequent visits to Assam and the Northeast have elevated the region’s strategic and political importance within national discourse. Modi is scheduled to attend another public gathering in Guwahati on 14 February, where he will inaugurate the third bridge over the Brahmaputra connecting Guwahati and North Guwahati. The historical parallel is not lost on observers: India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, inaugurated the first bridge over the Brahmaputra in 1963. The comparison subtly reinforces the BJP’s effort to position its leadership as transformative and historically consequential for the region.

There is also an expectation that sustained high-level attention could translate into more decisive action on protecting land and livelihoods, particularly in remote and vulnerable areas of Assam and the wider Northeast. For many communities, frequent visits and high-profile announcements raise hopes of meaningful change—hopes that remain only partially fulfilled in the absence of structural resolutions to land rights, ST status, and ethnic security. The recent tensions in Karbi Anglong between indigenous and migrant communities illustrate the layered complexities that continue to define the region.

As Assam approaches another election cycle, the challenge before both the state and central leadership lies in aligning development with inclusion. Whether initiatives like the second Legislative Assembly complex in Dibrugarh come to symbolise genuine decentralisation or remain primarily electoral markers will depend on how sincerely and transparently long-pending demands are addressed in the months ahead. The Dibrugarh event, therefore, was not merely about foundations being laid in concrete—it was about political foundations being tested in a state where development, identity, and power remain deeply intertwined.