The Shipki-La (Tibetan: སྲིབ་སྐྱིད་ལ།) is one of the highest cross-border trade passes in the Trans-Himalaya. La is a Tibetan term which refers to as Pass. It can be called either Shipki- La or Shipki Pass rather than naming it as Shipki-La Pass. It is situated on the Indo-Tibetan border in the western Himalayas, serving as a watershed boundary between the Kinnaur district of Himachal Pradesh, India, and Diya (Tibetan: བསྟི་ཡག་) town in the Zanda County of the Ngari Prefecture, Tibet. For centuries, it served as a vital trade and cultural corridor between India and Tibet.

Before the advent of modern state-sponsored infrastructure and the monitoring geopolitical maneuver, Shipki-La was a major corridor that facilitated economic and cultural exchanges between two civilizations – India and Tibet. However, following the Chinese occupation of Tibet and subsequent Sino-Indian border dispute, this centuries-old exchange was curtailed, causing many traditional trading communities to lose their livelihoods.

Despite partial geopolitical tensions, both India and China are cautiously seeking to revive the cross-border trade exchange for building the Asian century.

The opening of eco-tourism on the Indian side has further boosted the significance of Shipki-La trade and its surrounding border region. At the same time, China has been constructing “modern socialist villages” in Shipki village in Tibet for relocating its human settlements and building military infrastructure. This dichotomy of developments thwart a prospect of the Indo-Tibetan border trade.

This paper aims to explore the socio-economic and political-cultural significance of the Shipki-La trade corridor for bringing its ancient ties and current bonds between China, Tibet and India.

Historical roots of cross border exchange

Shipki-La stood as a historical witness to the region’s evolving socio-political developments and cross-border exchanges. For centuries, it was a vital passage for the movement of people, culture, knowledge, and trade between Tibet and India. These cross-border exchanges were well-established before the modern state-oriented capitalist system emerged.

Notable historical records dating back to the 17th century describe Shipki-La as a critical trade route connecting Tibet with the Kingdom of Bushahar (also known as Khunu), Ladakh, and Kashmir. In 1679, the Ganden Phodrang government of Tibet and Raja Kehari Singh (reigned 1661–1686) of Bushahar signed a treaty that guaranteed the safety of traders and ensured free and fair trade between in the regions.

Traders from Kinnaur, Spiti, Lahaul, Ladakh, and Punjab exchanged goods such as Indian tea, spices, and agricultural tools for Tibetan wool, salt, and livestock, including horses and goats. These exchanges were governed not by written contracts, but by gamgya, a traditional folk oath of mutual trust. These trading relationships were maintained across generations and often symbolically sealed by breaking a twig or a stone, with each party keeping one half as a token of their agreement.

This centuries-old system raptured following the Sino-Indian War in 1962. Subsequently, the pass was sealed, and cross-border interactions remained suspended for decades.

Formal resumption and modern trade

Following the normalization of India-China relations, the two countries signed a memorandum on 13 December 1991 to resume border trade. Shipki-La was formally reopened on July 16, 1994, under a regulated framework. In its first year, with 90 Indian traders crossing the border. As per a testimony revealed by an eyewitness of exchange during the 1996-1998, Tibetan traders demanded huge quantities of plastic materials from India rather than essential goods. The border trade continued under this system until happened the Galwan Valley confrontation between China and India in 2020.

Trade framework and economic dependence

On 16 December 2025, The New Indian Express detailed the 36 export items and 20 import items through Shipki-La which remain tightly regulated. Imports are restricted to 20 items notified by the Union government of India, including wool, pashmina, sheep skin, yak tails, yak hair, salt, shoes, blankets, quilts, carpets, and herbal medicines. Exports from India are limited to 36 items, such as coffee, tea, barley, rice, wheat, flour, dry fruits, tobacco, cigarettes, canned food, spices, watches, utensils, shoes, and handloom and handicraft products.

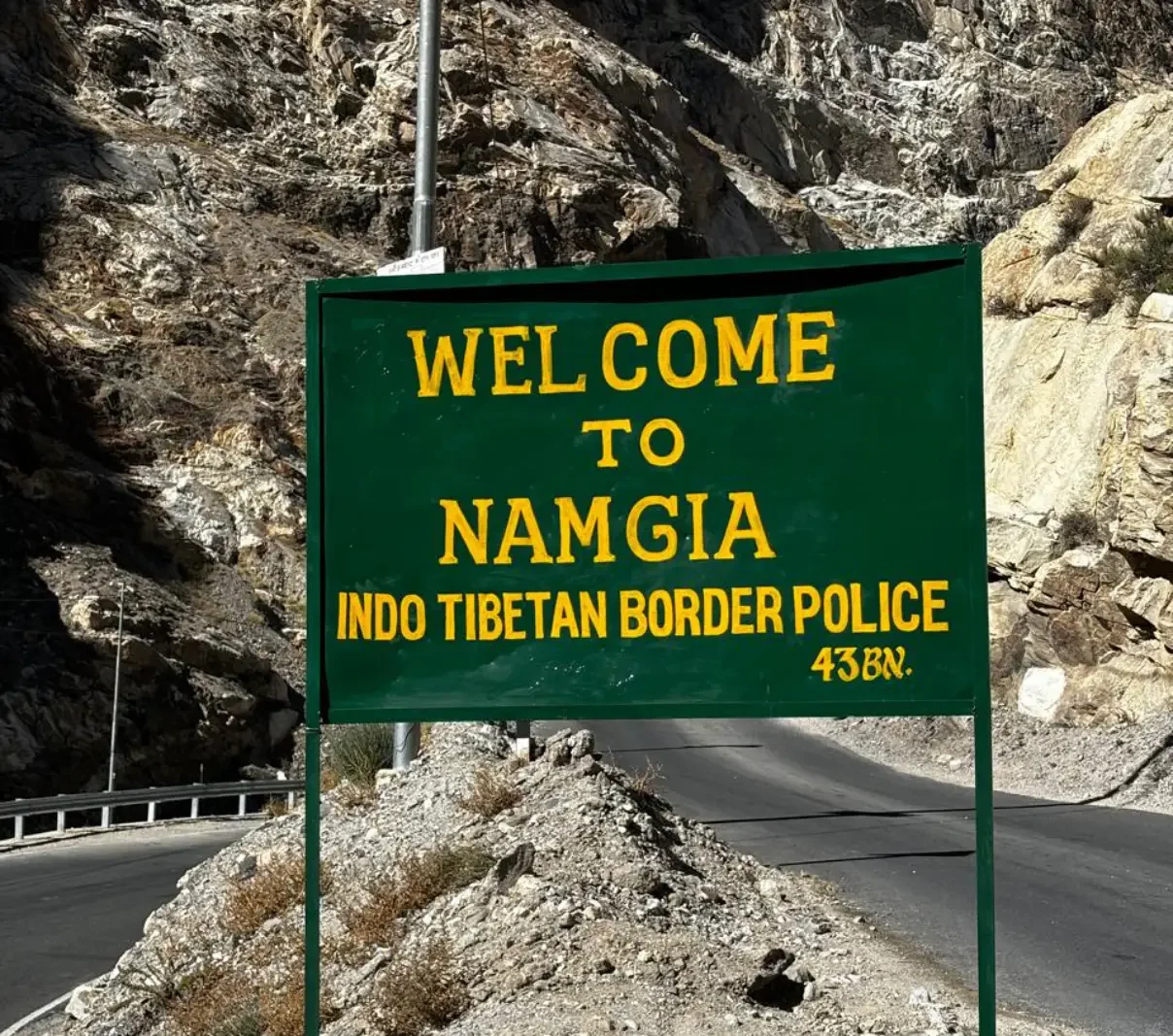

This regulated barter trade sustains at least 14 border villages in upper Kinnaur, including Namgia, Chuppan, Nako, Pooh, and Chango. Trade passes, which allow registered traders, are mostly from Nako, Chuppan, Chango, and Namgia to travel to Tibet. This trade trip typically happens during the months of September and October. According to data provided by The New Indian Express on December 16, trade participation has fluctuated, 71 Indian traders crossed in 2015, 75 in 2016, 34 in 2017, 37 in 2018, and 45 in 2019. The peak year was in 1994, when 90 traders participated and crossed through Shipki La to Tibet. The trade was suspended during the covid-19 pandemic, subsequently terminated aftermath of the Sino-Indian border clash in the western sector in 2020.

Recent developments in the region

After a five-year suspension, India and China agreed in August 2025 to resume trade through Shipki-La and other designated border passes. A review meeting of concerned departments and stakeholders was held on 15 December 2025 under the chairmanship of Deputy Commissioner-cum-Trade Authority Amit Sharma to assess institutional and logistical preparedness.

In a significant shift from India, Shipki La was officially opened to domestic tourists on 10 June 2025, for the first time since 1947 as part of a broader strategy to promote border tourism. While tourism has begun, cross-border trade between Namgia on the Indian side and Jiuba (CH:) on Tibet side has not yet resumed. Following political clearance from the Ministry of External Affairs in December 2025, trade operations are scheduled to officially restart in June 2026 after a six-year hiatus. Local authorities in Kinnaur are currently conducting preparatory reviews for logistics, security, and trader registration to facilitate this upcoming 2026 trading season.

Zero point border tourism

According to reports from The Indian Express and official data from the Himachal Pradesh Government, single-day footfalls reached a record 282 visitors on 22 June 2025. This surge followed Himachal Pradesh Chief Minister Sukhvinder Singh Sukhu’s formal launch of the “Border Tourism” initiative on 10 June 2025.

China’s infrastructure development near the Shipki La in Zanda (CH: Zhada) County, Ngari (CH: Ali) Prefecture, is highly advanced and strategically oriented. It consists of a network of Xiaokang (well-off) border defense villages that are deliberately designed for dual-use purposes for supporting both permanent civilian settlement and rapid military mobilization.

Among these settlements, Shipki Border defense village (CH: Shibuqi), which is situated 5km away from Shipki La zero point watch post. It is a primary frontline village on Tibet’s side. It has been upgraded with modern housing and administrative facilities. The Shipki well-off border village is one of the first line of 427 border villages which China have been constructed along the Indo-Tibet border regions to consolidate its territorial claim.

Another prominent Xiaokang village is Zabujang. It also refers as Zaburang, which is clearly visible to Indian tourists from the Shipki La zero point. Zabujang is categorized as a model village, which has featured by dense row-house construction. Such layouts not only support civilian habitation but can also serve as physical obstacles or fortified positions in potential conflict scenarios.

These border villages are well connected by high quality motorable roads linking them to major transportation corridors, including the G-219 highway. They are further supported by advanced telecommunications infrastructure, such as 5G networks and surveillance towers, enhancing both civilian connectivity and military command and control capabilities.

Chinese narrative on Shipki-La and border trade

The Chinese state-affiliated media and think tanks perceived the Shipki-La (CH: Shibuchi or Sibgyi La) as a historically significant Himalayan corridor and an important branch of the ancient Silk Road linking to Tibet with South Asia. According to Chinese accounts, the pass lies in Zada County in Ngari region of Tibet and was formally designated in 1993 as a Sino-Indian border crossing connecting Jiuba in Tibet with Nako in Himachal Pradesh to facilitate the movement of people and goods.

Chinese official has stated that India-China border trade has a long history that dated back to the 7th–9th centuries. China tries to link Shipki-La trade route with the Silk Road. This narrative asserts a Chinese supremacy over the pre-modern diplomatic, commerce and religious exchanges in the region. Backing these claim, Chinese historians have manipulated Tibet’s historical relations with the Ming and Qing dynasties, which project Tibet as a commercial bridge between China and South Asia. These exchanges were indeed conducted under Tibet’s own political authority and commercial institutions as independent nation.

Later, Chinese blames the British to disrupt the traditional trans-Himalayan trade by signing “unequal treaties” with Tibet and other Himalayan states.

A Tibetan scholar, Professor Tsering Shakya, argues that the People’s Republic of China’s administrative and military consolidation after 1951 was the primary driver in dismantling these centuries’ old networks across the Himalaya.

After signing the 1954 Sino-Indian Agreement, China regarded the agreement on “Trade and Intercourse” with India as a normalization that abolished colonial era privileges. In fact, it was the formalization of new restrictions imposed on previously autonomous trade practices between Tibet and the Himalaya.

In the preamble of 1954 agreement, India formally recognized Tibet as the “Region of China”. Since then, China perceived border trades including through Shipki La is portrayed as a stabilizing mechanism for frontier regions and a “barometer” of Sino-Indian relations.

While acknowledging that border trade constitutes only a small share of overall bilateral trade. Chinese media underscore its political and social importance in easing border tensions, rebuilding mutual trust, and sustaining the livelihoods of border communities. At the same time, Chinese commentary frequently features the underdevelopment of border trade to harsh geography, infrastructure constraints, and what it characterizes as unilateral restrictions imposed by India on trade items, participants, and operating periods.

Local voice on Shipki-La trade

To clear and precise information, we interviewed former traders from upper Kinnaur who registered and participated in Shipki-La trade exchange for many years ago. According to them, Shipki-La trade is vague and constrained.

According to Dorjee Negi, a resident of upper Kinnaur, “border trade through Ship-ki La played a crucial role in the past due to the region’s geographical isolation. Kinnaur is far from mainland Indian cities and lies close to the Shipki La border, making access to essential goods extremely difficult earlier. Even necessities such as salt were scarce at the time. In contrast, today such items are easily available in local markets of region.

Dr. Dondup Negi recalled his grandfather’s memory retention, in which he illustrated that historically, goods such as cotton, sheep, butter, and chura were imported from Tibet, while products like Brown sugar, masala, honey, tulip oil, and walnuts were exported. Kinnaur itself had limited local production. So, many of them served as middlemen. His grandfather participated in the trade 60 years ago. Trade with Tibet eventually stopped approximately 25–30 years ago.

While tourism has begun to develop in the region since last year, Dorjee Negi believes that border trade is no longer essential, as most goods are now readily accessible. However, he notes that if trade were to take place with an independent Tibet, it would still be meaningful, as people on both sides historically supported one another. He also points out that the king of Rampur in once maintained strong relations with the Tibetan authorities.

Despite frequent discussions by the central and Himachal Pradesh governments about reviving the Shipki La border trade, He argues that trade no longer holds the same importance it once did. Today, there is no scarcity of essential goods, and since the trade is to be with China, who He believe is an unpredictable with whom there is no mutual trust. He feels that it makes little difference whether the trade resumes or not.

He further recalls that about 20 years ago, a large market existed at Shipki La where only trade took place, and traders were not permitted to cross into Tibet as they had in earlier times. Ultimately, He believes that even the absence of border trade at Shipki La may be preferable, given the uncertainty surrounding China’s actions. If trade were to resume, he expects it would be limited mainly to animal-related products.

Policy pathways, challenges, and future prospects at Shipki-La

Despite renewed momentum of Shipki-La trade, physical challenges remain unchangeable. The 28-kilometre stretch from Namgia to Shipki-La is barren and lacks basic amenities such as rest stops, medical facilities, or eateries. The extreme climate further limits the access, the passes are typically open only from June to mid-September, and sudden weather changes make prolonged stays hazardous.

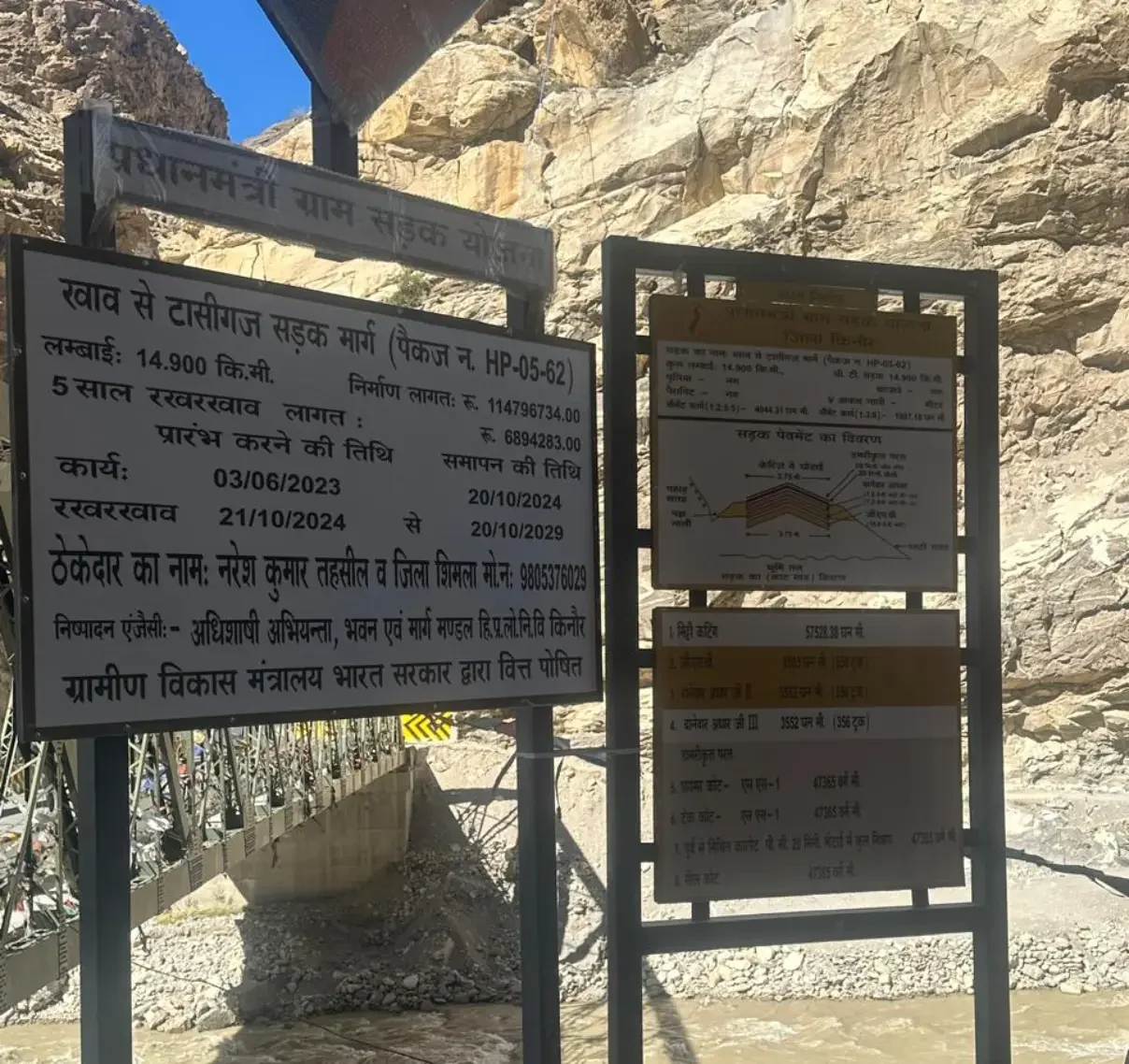

For Shipki-La to evolve into a durable and sustainable model of border trade and tourism across the Himalaya, a coordinated set of policy interventions is essential. Upgrading the existing 7–8 km mule track into an all-weather motorable road would significantly enhance trade efficiency and tourist access, reducing dependence on slow, labor-intensive transport systems.

China has constructed a tertiary road to Shipki-village which is directly connecting to the Xinjiang-Tibet Highway (G-219). It provides handsome subsidies to settlers in its border region. It is rapidly transforming a Chinese military cantonment region, where the largest Chinese military station is currently constructing in Tashigang, which would be a pivotal commend and control center of Xinjiang and Tibet military districts.

Spiritually, Shipki-La is the most accessible pass in the western Himalaya that offers the shortest route to Mount Kailash. It is formally integrating the Kailash Mansarovar Yatra network that could generate high-value religious tourism while strengthening India’s strategic presence in the region. As per a report published by Amar Ujala, a Himachal local Hindi Newspaper, “Himachal Pradesh Chief Minister Sukhvinder Singh Sukhu informed the central government that the Shipki La route linking Gartok to Darchen and Lake Mansarovar is comparatively shorter than alternatives”.

In this context, Himachal Pradesh Revenue Minister Jagat Singh Negi has welcomed the resumption of India–China border trade via Shipki-La, citing its potential to boost employment and regional economic growth.

Historically, the development of Shipki La had been closely linked to the Old Hindustan-Tibet Road, a major trade road that built by Lord Dalhousie in 1850 to connect the northern India with Tibet. This “Great Hindustan-Tibet Road” served as a primary route for the ancient silk and wool trade, running from the Indian plains (Kalka) through Shimla and Kinnaur Valley to the Shipki-La on the Indo-Tibetan border. Incorporating this heritage corridor into modern policy would allow for a unique blend of heritage tourism and modern market.

Restoring historical and heritage rest houses (Dak bungalows) and marking segments of the original bridle path could attract history enthusiasts and trekkers, effectively rebranding the route from a transit point into a “Living History” corridor that celebrates its legacy as a vital link in the Trans Himalayan trade network.

To ensure that economic gains must be locally oriented, tourism-related enterprises such as kiosks, homestays, and small service units should be reserved for residents of border villages like Khab, Namgia, and Tashigang in Kinnaur. This would prevent rampage tourism and the leakage of benefits to external actors. In parallel, high-altitude villages such as Namgia or Langza could be developed as astro-tourism hubs and zero-point border tourism.

Shipki-La stands at a critical juncture. Its revival is not merely about reopening a trade route but about redefining how India’s approach toward border development. As contrasting Indian and Chinese narratives underscore, border trade at Shipki-La is as much a geopolitical pivot as it is an economic exchange and historical significance. Whether the pass emerges as a sustainable success will depend on long-term planning that respects its historical legacy while navigating contemporary geopolitical representativeness with strategic transparency.