Borders are ubiquitous, and so are their contestations. Borders do not only mean territorial limits but have diverse connotations attached to them. However, with borders come divided lands followed by unfortunate events of the division. New forms of governance and sustenance develop, which leads to several borderland narratives, some new and interesting, while some sad and tragic. In my quest to find out more about the very lesser known border tribe-Tangsas, I visited the last known town in eastern India called Nampong, a few kilometres away from the famous Pangsau Pass, dividing India and Myanmar. The demarcation of the border in 1967 made the presence of the state by delimiting the areas that were once the passage of the people and the continuity of ideas and culture. The mental maps of the people living in the pockets of Patkai Hills thus changed forever. Not only did the overnight activity of border demarcation imply a lot of contestations, but it also left huge implications over traditions, language, culture, and societal relations for the generations to come.

We are very different from you. Our culture is very unique and different from that of people living on the plains. You wouldn’t understand how difficult and painful it is to see it all withering away.

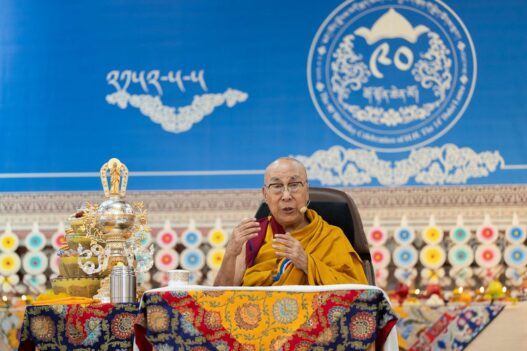

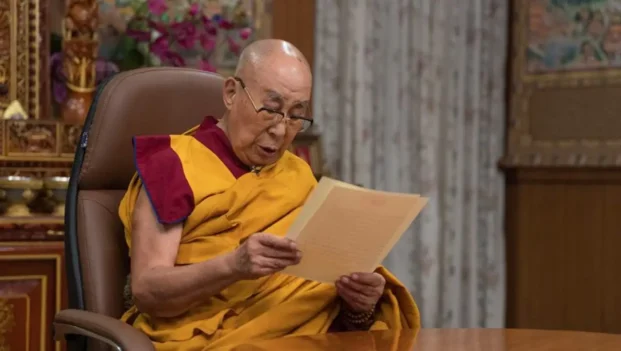

These were the emotions of H K Morang when I first pursued him, inquiring about how is it to be a frontier tribe. Being at the border not only adds a security dimension necessitated by factors of protection of the national interest, but it is also about limitations on the tribe’s consciousness of identity and belonging. It hurts to have to be so cautious and formal even when meeting one’s own relatives. A little-statured man, sipping ‘phalap’ (smoked tea) on his veranda while his kids were getting ready for work in the fields, was what my first meeting with Morang was. This is a common sight in Nampong’s “bastis,” or residential areas, located just beyond the city’s central market.

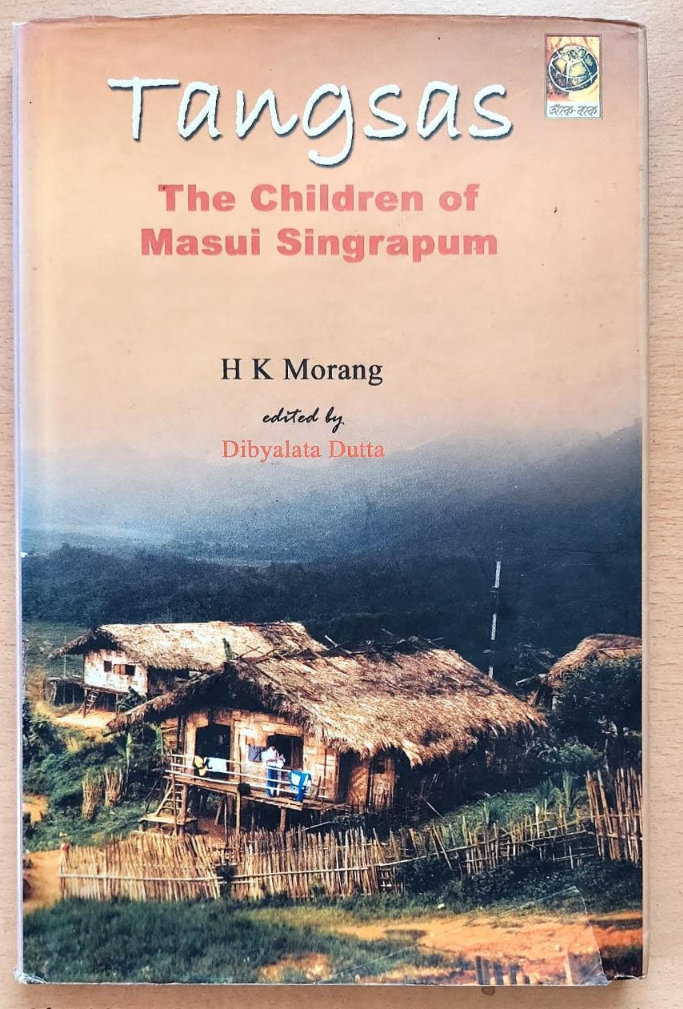

Well-known among Tangsas for his dedication to archiving the tribe’s past, Morang gave me a copy of his proud work, ‘Tangsas: The Children of Masui Singrapum’, saying, “The sad reality about me being a Tangsa is that I am not who I was at birth.” He claims that the Tangsa people originally came from a mountain in the east of Myanmar known as Masui Singrapum. However, many clans within the tribe hold divergent views about where the kins originally emerged from. Although it is unknown when or how the Tangsa people first arrived at Changlang (Arunachal Pradesh), their current main settlement, we can infer from the work of Hendrik van Loom that “the history of man is the record of hungry creatures in search of food, which was plentiful thither man has travelled to make his home.” Therefore, it stands to reason that people would migrate to areas where food was more readily available.

In our ensuing talk, he expressed his sadness that the community had changed so much since the determination of its borders that even the most senior members, like himself, no longer felt deep, abiding pride in their identity as Tangsa. It saddens him that the majority of his people have abandoned their ancient rites and traditions in favour of Christianity and Buddhism. The Tangsa tribe has made concessions in the areas of culture and tradition, demonstrating that every new development has been deliberately shaped in a form that strengthens the Tangsa’s social and political standing in the wider world.

Consciousness about one’s identity becomes a much-contested discourse at the border because of the constant deconstruction and reconstruction of their traditions and cultures to meet the ongoing pressure of integration with the larger part of the nation. The relationship between borders and identity has been a popular subject among the various scholars working on borders. And indeed, borders have a direct impact on constructing and moulding an identity, while at the same time questioning one’s belonging.

The tribes along the border of India-Myanmar though have a unique ‘Free Movement Regime’, but the stringent security protocols for movement across borders have gradually lessened these movements, which have de-constructed their identity by various means of adaptation. Also, in due course of India’s independence, the centre became slowly conscious of the need to secure its borders in the North Eastern part of India, which mostly shares its borders with the neighbouring nations. The cartographic decision of the British, which was practically non-reversible meant that the tribes not only lost their families but also their traditions and practices. This loss of values and way of life can never be replaced, which is the saddening reality for many borderlanders at the India-Myanmar border.

According to Morang, the ethnic counterparts of Tangsa who are currently in Myanmar, known as Rangpang/Pangmi/Heimi, are part of the same larger group of Tangshang Nagas; nevertheless, they have adapted to distinct economic, social, and cultural settings due to the international boundary. Because of the division, the same tribe grew and adapted under different government regimes. Furthermore, elders like Morang, who have seen the expanding contours of growth in numerous sectors on the Indian side, can now confidently proclaim, “I know they are my brothers, I know they are my relatives, but I also know I am Indian and they are foreigners.” They are now considered outsiders. This has once again had an effect on how people perceive their own existence. They have rebuilt their identity, which today projects a new multifaceted identity that draws on both their traditional ethnic history and their modern multi-religious and socioeconomic present.

It is true that people’s identities are most closely associated with their ethnic and linguistic affiliations, yet identities frequently undergo shifts as a result of the many different border customs and crossings.

Everyone’s experiences of boundaries are unique to them since they are shaped by their environments and the scales on which they are experienced. The Tangsas are a prime example of a border tribe whose way of life, identity, and sense of belonging are all influenced by the presence of borders, which also have distinct symbolic and psychological connotations and emotions for all border tribes.