How minuscule and transient are human lives, and even civilisations? Just specks and fleeting moments in the grander scheme of things. Exploring the banks of the river Brahmaputra is like taking a stroll through time, where our lives and civilisations seem like mere whispers in its eternal flow. This mighty river has been flowing for centuries through different territories, that different people, at different times, have marked parts of it as ‘ours’ and ‘theirs’.

Known by different names like Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibet, Siang in Arunachal Pradesh and Luit in Assam, it holds the secrets of countless stories woven into its waters. Imagine deciphering its hushed stillness or rhythmic rumblings—unlocking the tales of migration, resilience, destruction, and dreams that it has silently witnessed over the centuries. The Brahmaputra stands as a perpetual spectator to Assam’s rich tapestry, an entity of veneration that echoes the heartbeat of a vibrant history and an unwavering identity.

It flows some 1,800 miles (2,900 km) from its source in the Himalayas to its confluence with the Ganges (Ganga) River, after which the mingled waters of the two rivers empty into the Bay of Bengal. In Assam, the river is mighty even in the dry season, and during the rains its banks are more than 5 miles (8 km) apart. Between Dibrugarh and Lakhimpur district, the river divides into two channels—the northern Kherkutia channel and the southern Brahmaputra channel. The two channels join again about 100 km (62 mi) downstream, forming the Majuli island, which is the largest river island in the world.

Situated in a valley along the Brahmaputra river, Dibrugarh, the headquarters of Dibrugarh district in Assam is an industrial city with sprawling tea gardens. It is an important commercial centre, a port, and a rail terminus. Intrinsic to the Assamese identity, memory and heritage, ‘Luit’ as is called in Assam, the river Brahmaputra has been a major source of livelihood throughout the state. Numerous communities sustain on the river’s bounties, serving as a major provider for their basic necessities. Among them are the potter and fishing communities who have a deep association with the river, spanning generations over decades. Fishing has been the primary occupation for many, although seasonal.

At daybreak, the Brahmaputra river bank is a bustling site with fishermen rowing their boats and casting their fishing net, while some others segregate their catch at the riverbank to sell it in the town market. For the 43 year old Pushpa Ram Das, making it to the river early morning to fish has been the most important and routine task of his day, for years. Like many others who were engaged in the pecuniary hubbub at the river bank, fishing has been the primary profession of his family for generations.

The community he belongs to is one of the sixteen Scheduled Castes of Assam. During the monsoon season when the water level swells even causing floods, fishing and earning from it comes to a screeching halt. During those months (July-September) Pushpa and other fishermen sustain themselves with the meagre amount they earn by working as daily wage labourers, on ‘hajira’ (a payment made or a labour on the basis of hours or days worked). A good catch during the fishing season earns them around RS.400-500 per day. He highlights that these earnings only suffice for a hand to mouth existence, making it challenging to ensure a brighter future for his children and a way out of poverty for them.

Pushpa, a father to two bright kids, a son, and a daughter, only had the opportunity to study until the 5th standard. Due to their poor economic condition, he was compelled to enter the fishing business with his father. Despite his limited education, Pushpa considers his children’s education to be of utmost priority. Having spent a significant part of his life in the river, he says, he wants to ensure that his children do not meet the same fate at any cost. The only government scheme or ‘assoni’ his family currently avails is the‘Orunodoi’ scheme of the state government under which, his wife gets a sum of Rs.1000 through DBT (Direct Benefit Transfer).

In addition to Pushpa’s perspective, 50-year-old Dhananjay, a father of three children, shares that he pays Rs.1,500 to rent a boat for fishing. Acquiring a boat, which lasts only 5-6 years, comes at a substantial cost of Rs. 20,000, excluding maintenance expenses for coloring and repairs. Applying color to extend a boat’s lifespan costs around Rs. 3,000-4,000, a process that needs to be repeated every 5-6 months.

He says, with the cost of living exponentially increasing and earnings ever stagnant, sustaining and meeting basic needs have grown trickier than ever. Lacking essential amenities or support, they find themselves trapped in a cycle of poverty, struggling to achieve a better standard of living. Similar to Pushpa’s wife, the ‘Orunodoi’ Scheme is the sole government assistance that Dhananjay’s family relies on.

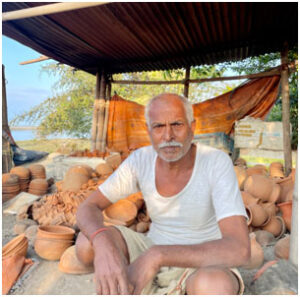

At the opposite end of the river bank, the ‘Kumhaars’ or potters have cultivated and passed down the art of pottery through generations. Among them is 60-year-old Pandi and his family, whose father migrated to Assam in the 1950s from Bihar. Like him, his wife was born in Assam and her father had migrated from Bihar during 1947.

Pottery has been the only profession in his family and the sole source of income for generations. He dedicated himself to ensure his daughter and two sons received a formal education. To him education seemed like the only way to climb out of poverty and a means of social mobility. While his eldest son managed to push himself out of the family profession by obtaining a degree in hotel management and now holds a position at the front desk of a hotel in Dibrugarh town, his two younger brothers found themselves compelled to persist in the pottery business despite their educational qualifications. The younger son graduated with a B.Com degree from Debru College, while the youngest son holds a B.Sc (PCM) degree.

Education has long been recognised as a key factor in helping individuals move up the social ladder, through the acquisition of human capital. By acquiring human capital through education, one gets the chance to increase their earning potential and access to better-paying jobs, leading to an upward social mobility. However, the relationship between education and social mobility is complex and is influenced by various factors. To achieve social mobility through education, one needs to wrestle with systemic inequalities, failing which qualified individuals are forced to be where they are no matter how hard they try.

Chandan Pandi, Pandi’s younger son, was born in Assam and has been honing the art of pottery since 2004. From a young age, his ambition was to secure a government job. Despite successfully passing three out of the four phases for the Indian Army soldiers General Duty (under the present Agniveer scheme) on two occasions, he fell short of making it to the final list.

Due to the need to sustain daily living expenses, he dedicated 10-15 hours daily to the family pottery workshop, leaving him with insufficient time to prepare for the Common Entrance Examination (CEE) required for the final selection phase. Consequently, he exceeded the age limit for government job applications and now works full time in the family workshop. He is married and has a 1.5 year old daughter today, for whom he feels wedged between making plans for her better future, and a sense of scepticism born out of what he has seen in life.

The workshop sources clay in bulk from various parts of Assam at a cost of Rs. 7,096 per truck, which is sufficient to produce approximately 1 Lakh Diya (earthen lamps).

The family dedicates 4 to 5 months to craft and sell these Diya in local markets within the district. However, the traditional earthen lamps face stiff competition from mass-produced plastic or candle wax alternatives. When asked about diversifying their earthen products, Chandan explains that the clay they can afford is of lower grade. Consequently, it is impossible to create other ceramics as the clay tends to crack beyond a certain size due to its rough texture laden with impurities.

On the other side of the dyke built around the river bank resides Hira Lal Pandi, whose father had migrated from Bihar to Assam in 1950s. Engaged in the pottery trade for over six decades, his family’s roots have firmly intertwined with the riverbank lifestyle. Severed from ties with relatives left behind in Bihar, life along the riverbank are the only memories left for him.

In the mad rush of living and surviving, we seldom pause to look around and acknowledge fellow travellers, their tribulations, our shared humanness and all that comes with it.

While the rich and powerful are immortalised through majestic memorials and tributes, the stories of people who are pushed to the peripheries wrap up their stories and keep it buried within themselves never to be shared, or known to anyone else and it eventually dissipates with the end of their sojourn. How do we decide which stories of strength, bravery and persistence deserves to be heard, recognised and honoured? How do we deem the life of one sentient being more important than that of other? It is such a quandary and an injustice.

The information contained in this article is provided on an “as is” basis. Informed consent was obtained from the participants for disclosure of personal information and media for the article.